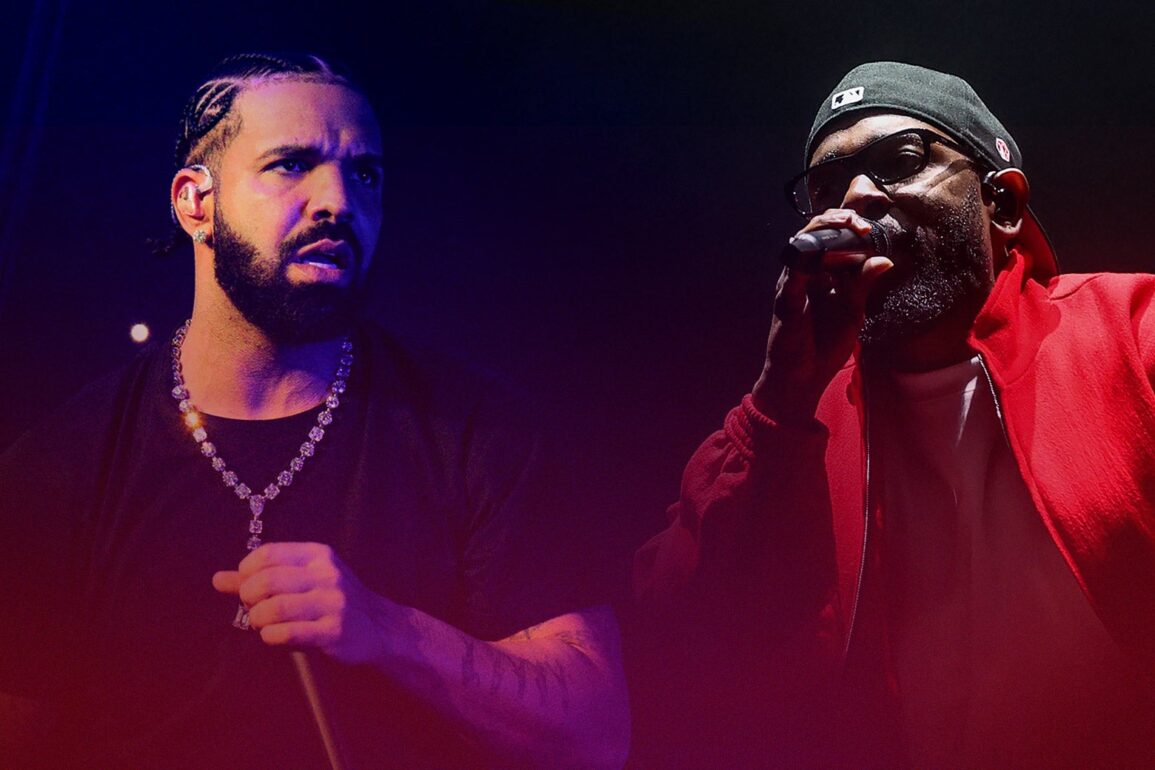

By late last week, the old heads were already sounding the alarms as it became increasingly clear that “The Heart Pt. 6”—Drake’s limp, blackhearted response to Kendrick Lamar—would be the final salvo in their electrifying rap beef.

Chuck D, the leader and frontman of politically minded Public Enemy, warned against indulging too much in the spectacle. “I was very clear on the boundaries of culture long ago,” he posted on X, the social media app formerly known as Twitter. “Gangster Rap was like dark hard liquor just because it’s sitting there doesn’t mean your narrow young ass can drink or handle it. … Straight out drama street rap was like a 40 and we all knew what that did long term. Look around.”

Questlove, the drummer for the Roots and a cultural ambassador of sorts, took to Instagram to share his disgust. “Nobody Won The War,” he wrote, almost exasperatedly. “This wasn’t about skill. This was a wrestling match level mudslinging and takedown by any means necessary—women & children (& actual facts) be damned. Same audience wanting blood will soon put up ‘rip’ posts like they weren’t part of the problem.”

Even Ice Cube—a pioneer of gangster rap and himself a participant in a number of legendary rap beefs—expressed concern about the ugly escalation between Drake and Kendrick. “Back in the day, you do a diss record, but it would stay kinda somewhat in the hip-hop community. Now it’s all over the world, all walks of life know what’s going on, and some people can’t really take that kind of humiliation,” Cube said in an interview. “Beefs are, you know, they’re volatile. So you always have to be careful that a beef doesn’t turn into a murder.”

Left unspoken but clearly not forgotten by these battle-tested veterans were the Tupac and Biggie murders, a dark cloud over hip-hop for almost 30 years now. It’s understandable why they—artists who were nearly as big as both when they were gunned down—would be traumatized by the prospect of living through more bloodshed involving the genre’s biggest stars. Every hip-hop beef will be measured against Tupac and Biggie, if only because fans and media have at turns exalted it for its viciousness and decried the tragic outcome. But for Chuck, Quest, and Cube, as well as many others of that generation, it was a formative moment. The grim realization these conflicts might spill out of the recording booth and into the streets forever changed the way some of us looked at these clashes. Was this business? Was this personal? Did it even really matter?

And though I was initially skeptical Drake vs. Kendrick would ever escalate to actual violence, I was forced to reconsider after a shooting at Drake’s home in Toronto last week left his security guard in serious condition and again, after a series of three alleged trespassers were apprehended outside his house on Wednesday, Thursday, and Saturday. In all of these incidents, it remains unclear who was involved and why, but it wasn’t exactly implausible that something bad, even something deadly, could happen.

When I think back to the year I spent researching and reporting for the podcast Slow Burn: Biggie and Tupac, I think about the many real differences between those two twentysomething stars who hadn’t yet tapped into their full earning power and today’s thirtysomething multimillionaires who are themselves basically corporations.

The circumstances leading to the rift between Shakur and Christopher “the Notorious B.I.G.” Wallace feel analog, a throwback to a time when less than a fifth of North Americans were even using the internet. The fuse was lit in November 1994, when Shakur was heading to a Times Square recording studio while facing a verdict in a trial for sexually abusing a fan.

Shakur desperately needed the $7,000 he’d been promised for the recording session that night. He was hemorrhaging money from legal fees and missing out on paying gigs. On his way into the studio, Shakur looked up at an eighth-floor balcony and saw a couple of members of Biggie’s affiliate rap group Junior M.A.F.I.A.

They exchanged greetings, and Shakur went into the lobby to catch an elevator upstairs. One of those Junior M.A.F.I.A. members, Chico Del Vec, told me they all considered themselves friends at the time. Shakur and Wallace were big fans of each other and even occasionally performed together. “We loved Tupac, man,” Del Vec told me.

But seconds later, when Shakur and his friends entered the studio lobby, two men wearing boots and Army fatigues robbed him and shot him five times. The men have never been identified.

By the time a wounded and bloodied Shakur left the studio on a gurney, he’d already decided that Wallace and his friends had set him up. “Tupac gets off the elevator, on the hospital bed, they wheeling him out … and he looking at us with his middle finger up, like ‘Fuck you niggas,’ ” said Del Vec, who died last August.

The friendship was over, just like that. Arriving at court the next day in a wheelchair, covered in bandages, Shakur was found guilty of sexual abuse. The judge allowed Shakur to remain free on bond while he recovered from his injuries. That gave the rapper lots of time to think about who shot him, and if his friends were actually his friends. Not surprisingly, he’d stew on this for the rest of his life and lash out at anyone he suspected of having had something to do with it—especially Wallace and anyone connected to him.

“The fact of the matter is that beef was really about Pac’s paranoia and the lengths that people around him would go to stoke it,” said Dan Charnas, author of The Big Payback: The History of the Business of Hip-Hop and someone featured heavily in that season of Slow Burn.

Charnas, who once ran the rap division of American Recordings in a joint venture with Warner Bros. Records, knows this better than most.

In 1996 Charnas represented a young rapper from the Bronx named Chino XL, who was then a fan of Shakur. In a song called “Riiiot,” on his debut album, Chino XL rapped a line that Shakur misinterpreted as disrespect: “By this industry/ I’m trying not to get fucked/ Like Tupac in jail.”

“Commas are really, really important,” Charnas said, laughing. “What he meant was, Like Tupac in jail, comma, I’m trying not to get fucked.”

Three months later, in the iconic but perhaps most incendiary diss track ever, “Hit ’Em Up,” Shakur boasted that he’d had sex with Wallace’s wife, the R&B singer Faith Evans. Near the end of the song, he also insulted Chino XL and other rappers who he believed had sided with Wallace. “And if you wanna be down with Bad Boy, then fuck you too/ Chino XL, fuck you too,” taunted Shakur.

Two lines later, Shakur issued a clear threat: “Motherfucker, my .44 make sho’ all y’all kids don’t grow!”

Talking to Charnas last week over Zoom, he shook his head ruefully at the memory. “Chino took that seriously. So there were back-channel communications that happened,” Charnas said. “And eventually, there was an attempt made on Chino’s life in Jersey. And nothing was worth that. Nothing is worth that.”

But Charnas, who spent years working in the recording industry, understands that beefing can also be a powerful marketing tool for artists.

In The Big Payback, Charnas traces the origins of the “diss track” to New York DJ John “Mr. Magic” Rivas, who was angered that the hip-hop group U.T.F.O. canceled a scheduled appearance at one of his shows. That launched a series of response songs, now referred to as the Roxanne Wars, because Mr. Magic commissioned 14-year-old rapper Roxanne Shanté to perform the first record, “Roxanne, Roxanne.”

“The ‘Roxanne Wars’ … were good for business,” Charnas wrote. The strategy was clear: “Dis somebody, draw them into a fight, and make money.”

It’s been a solid promotional plan for nearly 40 years now, boosting the careers of dozens of hip-hop artists, from KRS-One to 50 Cent. And as Charnas pointed out, rappers don’t really need a financial motive to go after each other anyway.

“I cringe a little bit when people say that people beef for commercial reasons,” Charnas said. “The fact of the matter is that artistic competition is baked into the culture. I don’t think that either Drake or Kendrick necessarily got into this with commerce as the primary aim. I think Drake does what he does and Kendrick does what he does, and both their egos and their creative trajectories are in opposition.”

But the benefits of the clash were clear once again on Monday, when Lamar’s infectious most recent track “Not Like Us” entered the Billboard Hot 100 at No. 1 and one of his previous Drake diss records, “Euphoria,” reached No. 3 in its second week on the list. Meanwhile, Drake’s Kendrick diss “Family Matters” reached No. 7. If there isn’t quite a consensus on the winner of their rivalry, at the least Lamar can claim an undisputed—and improbable—victory in streams and views over the most bankable rap artist of the past 15 years.

“I’d be very surprised if it really impacts Drake’s commercial standing in a long-term way,” said Dan Runcie, who runs the hip-hop business newsletter and podcast Trapital. “There may be some knocks or hits that he may take from some of the hip-hop purists and things like that, but I don’t think that’s going to materialize into ticket sales being any different.”

That’s why I was captivated by the most recent episodes of The Joe Budden Podcast, hosted by the 43-year-old retired Harlem rapper of the same name.

Budden is a much different sort of old head compared with the likes of Chuck D and Ice Cube. He never attained their level of wealth and prominence from rapping, but he carved out a respectable career for almost 20 years before transitioning to reality TV and podcasting, where he’s since become a major star. Budden also has his own considerable history of rap beefs, including a long-running one with Drake that flared up again last year.

The Drake-Lamar beef clearly energized him and his podcast co-hosts, and they chewed it over for more than five hours in an episode titled “Fancy Feast.” One of the more valuable services they provided for listeners, including me, was reminding everyone of the professionalism necessary to succeed in beef.

Budden marveled at the restraint of Lamar, praising his decision to wait roughly two weeks before releasing “Euphoria” to address Drake’s challenge to him in “Push Ups” and “Taylor Made Freestyle.”

“All that posturing that Drake was doing to get him out of the cubbyhole is not going to work,” Budden said, “because you’re dealing with somebody disciplined enough to play at their own pace that’s not going to let someone dictate how they feel or what they do.”

It was a reminder to the audience that Lamar had executed a carefully planned attack. Consider that Lamar released two songs on May 3: “6:16 in LA,” in which he claimed to have operatives in Drake’s camp, then the much darker “Meet the Grahams,” less than an hour after Drake dropped “Family Matters.”

“Wherever Kendrick was, a studio wasn’t far. … I think he might have been sleeping in there,” said Budden, proclaiming throughout the episode that Drake was thoroughly outclassed by Lamar. “When shit is going like this, you need to be 24/7 working. If you’re not prepared to do that, don’t beef.”

As Budden explained, Lamar was operating as a high-level artist and businessman. It was something totally different from 23-year-old Shakur’s recklessly lashing out at people he once considered friends after being mugged in New York and Wallace, years later, making the fatal decision to party in Los Angeles amid the so-called East Coast–West Coast rivalry.

There’s almost no chance that Lamar is going to haul off and assault a South Side Crip in Las Vegas, or that Drake is going to make the same kind of sloppy logistical and planning mistakes that Bad Boy Records made with Wallace in his final days.

These are now almost middle-aged men, at the top of their professions, with much to lose, producing a duel that will take its place among the best of all time, perhaps already surpassing Nas and Jay-Z, LL Cool J and Kool Moe Dee, Lil Kim and Foxy Brown.

“It’s somewhat of a false parallel because Biggie and Tupac never had a match of wits lyrically like this,” Charnas said. “It’s given us some moments, and I hope there’s no physical cost for it.”

Then again, the beef doesn’t require either of them to explicitly provoke a fight to cause bloodshed. It’s doubtful that it’s all really over, even though Drake seemed to indicate on Instagram on Sunday that he was pivoting to frictionless “summer vibes.”

And that same day, in a follow-up episode of The Joe Budden Podcast titled “When the Dust Settles,” the co-hosts seemed to have seriously considered the rebuke of Questlove and others. They also appeared shaken by the shooting outside Drake’s Toronto mansion last week.

“Some of these niggas are affiliated with real gang members,” claimed Antwan “Ish” Marby, making a direct comparison to Tupac and Biggie. “So now what happens if these niggas see each other in the middle of L.A.?”

In my reporting for Slow Burn: Biggie and Tupac, we covered the cluster of gang-related shootings that happened in Southern California following their deaths. At least three people were killed and several others wounded while Shakur was on the verge of death in a Las Vegas hospital.

Alex Alonso, a sociologist who studies gangs in L.A. and hosts the Street TV podcast, told me that Shakur’s shooting “created a snowball effect to where other people that weren’t even directly connected to the conflict were getting killed as well.”

And for me, that’s the true reminder here: When the beef turns violent, the rappers aren’t the only people at risk of becoming casualties. It’s the kind of reality that I hope Lamar and Drake consider when choosing their next move—or whether to keep this going at all.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.