CULTURED’s monthly column, Spatial Awareness, is meant to pull back the curtain (just a little) on some of the most original voices working in architecture today.

A lecture by the Jamaican-born architect Sekou Cooke is a mashup of podcast informality and concert-vibe energy. Cooke claims not to be a “hip hop head,” yet the curated soundtrack accompanying his academic reflections on hip hop architecture suggests otherwise.

The term “hip hop architecture” originated in the ’90s at Cornell University, where Cooke was a student. Over the years—and with Cooke’s help—it has grown from obscure academic framework to veritable cultural movement. The 50-year-old music genre’s tentacles have embraced dance, fashion, art, and literature; Cooke is popularizing the notion that it can also apply to architecture.

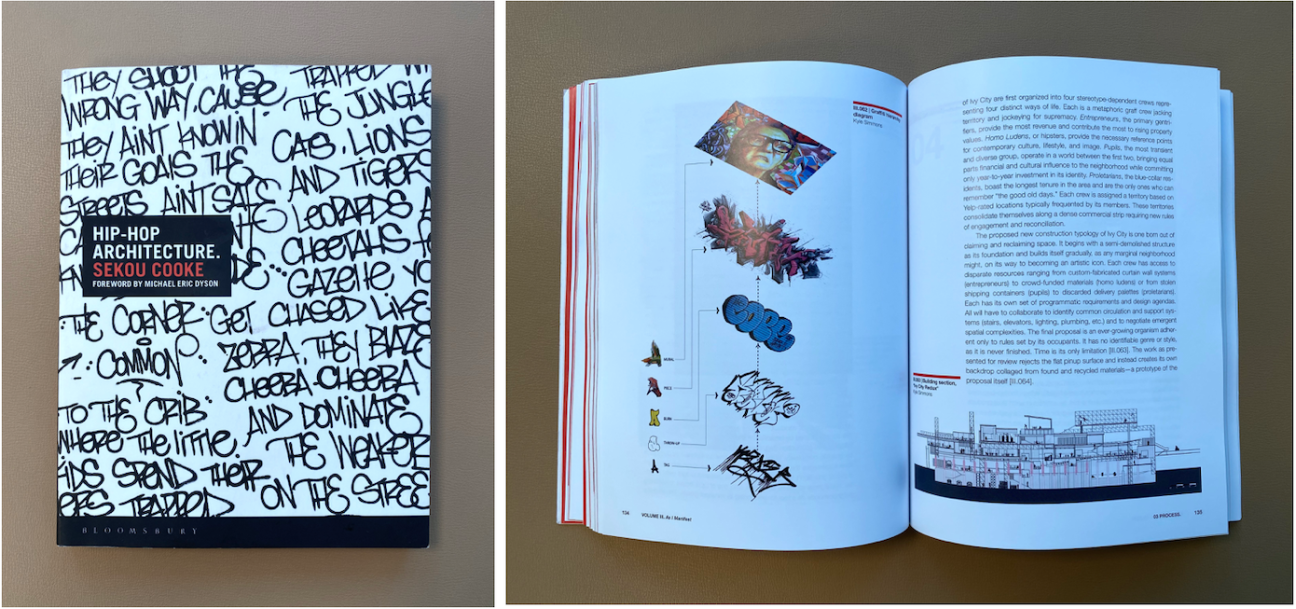

Like hip hop itself, Cooke is multidimensional: he counts urban designer, educator, curator, author, and new dad as part of his arsenal to reimagine spaces and buildings. Perhaps most importantly, his 262-page manifesto Hip-Hop Architecture from 2021 is the authoritative text on the built environment’s crossover with the tenets and attitudes of hip hop. Now, he’s working to develop Syracuse Hip-Hop Headquarters, a youth center in New York State that would serve as a hub for the movement.

In Hip-Hop Architecture, Cooke explores four elements of architectural production through the lens of hip-hop: remix is renovation, rap is construction, breakdance is form, and graffiti is surface. The book surveys projects by graffiti writer-turned-architect Stéphane Malka, conceptual artists Theaster Gates and Lauren Halsey, and architecture-trained artists Amanda Williams and Olalekan Jeyifous, among many others. The way Jeyifous describes the process behind his large-scale collage series “Surface Armatures”—“appropriating, reappropriating, intentionally misappropriating, and remixing over and over again”—would be familiar to any hip hop producer.

Cooke describes himself as a philosopher first—obsessed with ideas. He organized the seminal 2019 exhibition “Close to the Edge: The Birth of Hip-Hop Architecture” at Springbox in St. Paul, and his work was featured in “Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America” at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 2020. His architectural practice centers less on making buildings and more on designing spaces and experiences for people.

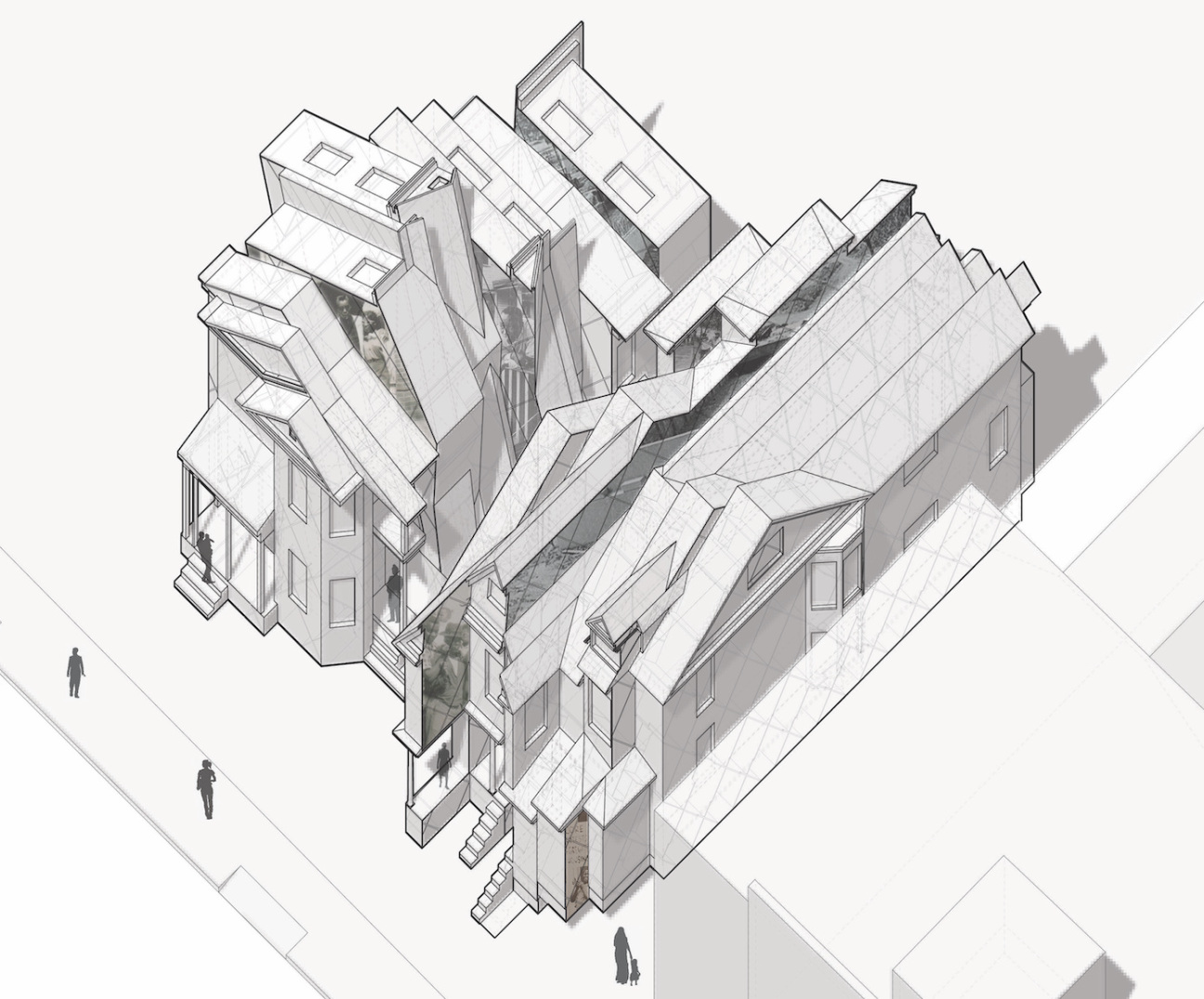

During a formative teaching stint at the School of Architecture at Syracuse, Cooke met Hasan “DJ Maestro” Stephens, a radio personality and the founder of the Good Life Foundation. The kindred spirits embarked on the ultimate manifestation of hip hop architecture: transforming a dilapidated dairy building into SHHHQ (Syracuse Hip-Hop Headquarters), a youth center that offers music lessons and business training to disadvantaged young people.

Conceived before the pandemic, SHHHQ has all the ingredients for significant impact, yet access to capital is a challenge; a campaign to raise $9 million remains nascent. One is reminded that while hip hop is a dominant force in culture, it is layered and iterative, lauded and critiqued; it is a challenge to the status quo, which makes it hard to receive support from establishment sources. Savvy philanthropists and foundation leaders would do well to buy Cooke’s book Hip-Hop Architecture and study how to construct a more equitable world by creating bespoke spaces for Black and brown communities.

IN HIS OWN WORDS

What was your favorite toy growing up?

In my memory, I didn’t have many toys. The toys I do remember were gifts from my cousin whose family had a bit more money than mine. He wanted to make sure that if he had a toy, I’d have the equivalent so that we could play together. I’d always have to be the bad guy though. If he had He-man, I had Skelator. He had Autobot Transformers, and I got the Deceptacons.

I also remember loving toys like Transformers that moved and changed form. Or, if they didn’t, I would change their form against their will. I was one of those kids who drove his mom crazy by always taking things apart.

Whose house would you live in (real or fictional) and why?

I have a pretty odd relationship with living almost anywhere. I can’t settle on one type of house or region or even environment that I’d like to live in. I could say something like the Jetsons house or Tony Stark’s Malibu mansion or a house I renovated outside of New York early in my career, but I’d still want to keep changing them. Then I’d pick up and move somewhere else.

What is your go-to uniform when you’re powering through a project?

Probably my pajama pants. If I’m really focused on and enthralled by a project, I’ll just roll right into it first thing in the morning before taking care of basic hygiene or bodily needs.

Who chooses the playlist in your studio?

Surprisingly, we work mostly audio free. If there is ever music in the studio, however, I’m certainly in charge of the playlist. I’ve ceded that role to others in the past with rare positive results.

What’s a trend in architecture you wish would die out?

All of them. Architecture shouldn’t be about styles or trends. We’re not the fashion industry, which has to renew itself twice a year. Our projects take deep consideration and reflection. They reference all the histories we have access to and project into possible futures. We should be designing spaces that last hundreds of years, not just a few decades. If you’re designing to fit into a current or (even worse) a past trend, just stop!

What is one detail of a structure that most people wouldn’t notice, but that you always look to for insight?

There’s a great Instagram feed @sexygutters that I love. I think I’m always trying to find ways to avoid adding gutters to buildings and praying for projects that don’t require them. If I could get one of my projects tagged on @sexygutters, I’d be super excited.

Are there any analog materials you return to in spite of the prevalence of new technologies?

I embrace all analog materials as a general practice. I sketch by hand, take notes by hand, read physical books, and even still use a Mayline [workstation] at the beginning of a project. I love using basic materials like wood, steel, concrete, brick. I’m never really on the hunt for the latest technological solution to any design challenge. I allow the technology to emerge as necessary throughout a project and even directly challenge the digital to act more human.

What is the most progressive architectural city you’ve visited?

Amsterdam, for sure (at least in how I understand the term “progressive”). Even the lowliest sidewalk or street sign is designed to a higher standard than most public buildings in the U.S. I’m still generally more impressed by a city like Cairo, where it’s almost impossible to figure out its underlying logics, yet it works beautifully and effortlessly in a frantically chaotic kind of way.

What is your last source of inspiration that surprised you?

I just started working on a project for a veterans memorial and, at first, I thought about completely rejecting the idea of the American flag altogether. Then I found there’s something really unique and fascinating about all its complex geometries. Now I’m thinking it might be the catalyst for the entire design.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.