In the organised chaos that is Chennai’s Kannagi Nagar stands a white facade of a three-storey building that captures ephemerality like no other. It carries a mural in grey that only appears as the sun goes up. The artwork is an intelligent shadow play that embodies a crisis that the resettlement locality, some 20-odd kilometres from Chennai city, is faced with every year: water shortage. The wait for the image every morning mirrors the neighborhood’s wait for water. Here, time repeats itself. For Daku (translates to bandit) aka Hanif Kureshi, time has always been a conduit for expression; a medium by his own admission.

In 2022, the streets of Fountainhas in Goa got introduced to dancing alphabets that play to the tune of the sun. He compared the catastrophic pandemic to the Spanish flu, pointing fingers at how history has this habit of repeating itself.

But one cannot help but wonder if his favoured medium could have been kinder, as the country now mourns the artist’s passing following a year-long battle with lung cancer. He was 41.

“Daku. What a badass, right? To make such political, powerful and fearless public art interventions in India at a time when public art was not even a thing!,” asks artist Shilo Suleiman, adding, “What a visionary builder and mentor to a community.”

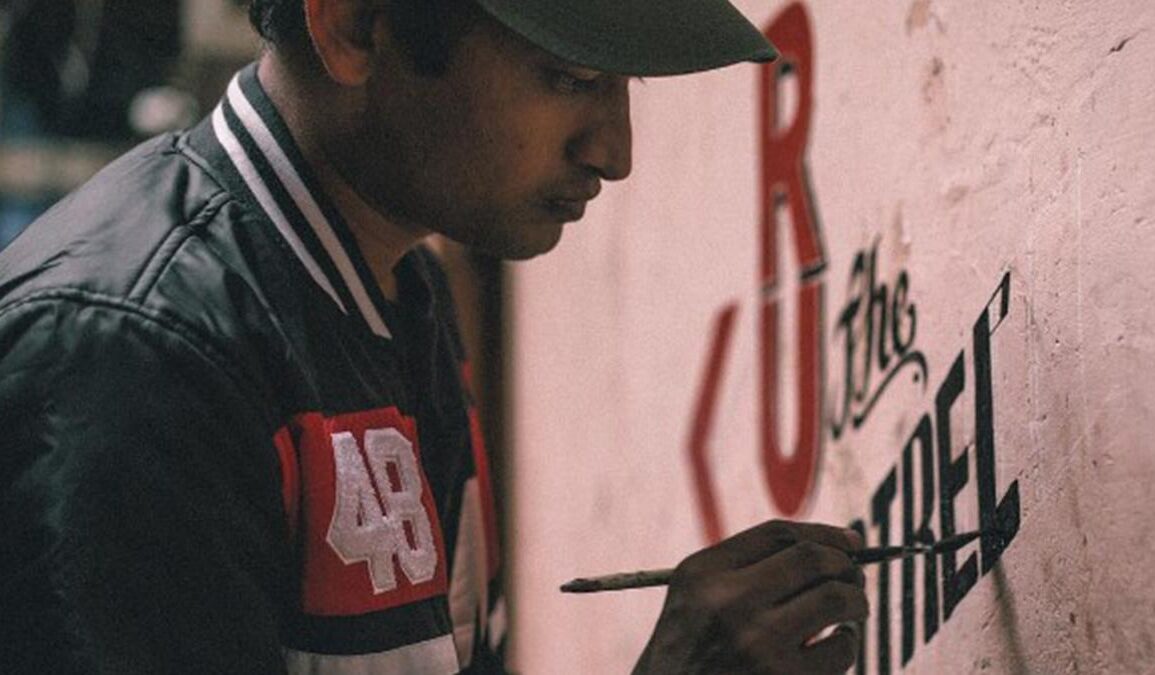

Artist Guido Van Helten spent days photographing local women at the docks. Their vast portraits grace the warehouse where people like them have carried on their traditional business for the 142 years of Sassoon Dock’s existence. The creative lead for this project was Hanif Kureshi

| Photo Credit:

special arrangement

For Shilo, Hanif was a mentor who quickly became a friend. “What he has done with the street art community, and how he brought us all together, and brought opportunities and infrastructure to the street art world, is a universe in itself.”

Hanif is remembered by a consortium of adjectives. Voracious. Inclusive. Loving. Passionate. A freaking genius! His work, right from the early 2000s, is a tour-de-force in the contemporary Indian art ecosystem. From humble beginnings in Talaja, Gujarat, he pioneered multiple movements that brought the ‘regional’ to the mainstream; he unapologetically and deliberately broke out of the white cube while also recognising the importance of creating an art market that the country can call its own; and most importantly he took art to the streets. Loudly. Sometimes as large flex boards that announce his arrival and at others, on stop signs with clear warnings: ‘Stop Gossiping,’ one such sign read in Delhi.

“Yet, he had a way of wearing his art so gently,” reminisces Riyaz Amlani, a longtime collaborator and friend. Hanif’s HandpaintedType is a pathbreaker project that to this day attempts to preserve the typographic practice of sign painters across India. “One of the first things I remember was how passionate he was about typography. It was one of his greatest loves. He was an analogue brain in a digital world. His love for people who worked with their hands was unmatched,” recalls Riyaz. The artist was a breath of fresh air in a contemporary art world that was still struggling to balance the duality of traditional and modern aesthetics.

Daku’s work at MUAF 2022-2023,

| Photo Credit:

St+art India

With the idea of community at its centre, the ambitious St+art India project that he co-founded with Guilia Ambrogi, Arjun Bahl, Akshat Nauriyal and Thanish Thomas in 2013, was the first formal step to democratising art through public-facing murals. In 2014, India’s first ever art district sprung up in Delhi’s Lodhi Colony.

Guilia recalls, “The first few projects were done all by ourselves. We were carrying paint buckets, pasting posters and transporting equipment. Nobody knew what we were doing. It almost seemed like street art was a game then, you know. And it was beautiful, because it was a bunch of crazy people together. The energy would never stop.”

There is also a quieter side to Hanif. Some of Guilia’s fondest memories are in Paris when the duo spent hours roaming around its streets, in curious pursuit of public art with their respective partners. And time spent in their first studio in Haus Khaz village by the lake.

At Khairadabad Flyover

| Photo Credit:

special arrangement

As years went by and St+art India grew as an institution, Guilia says that their relationship became all about balancing ideas. “I have never heard Hanif complaining. Even after the diagnosis, he never complained. He was the sun! So full of energy.”

Shilo recalls a conversation she had with Hanif earlier in January. “Even through his deteriorating condition, we have had long conversations on how artists feel as though we are immortal. We work hard, barely sleep and as containers of creative vision, we often forget that we are human, and need a routine. It’s my biggest takeaway following this loss.”

Published – September 25, 2024 05:07 pm IST

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.

Email

Remove

SEE ALL