Spirituality refers to the subject’s access to a certain way of being or to the transformations a subject must undertake upon himself in order to access this way of being.

—Michel Foucault

The choice of language and the use to which language is put are central to a people’s definition of themselves in relation to their natural and social environment, indeed in relation to the entire universe.

— Ngugi Wa Thiong’o

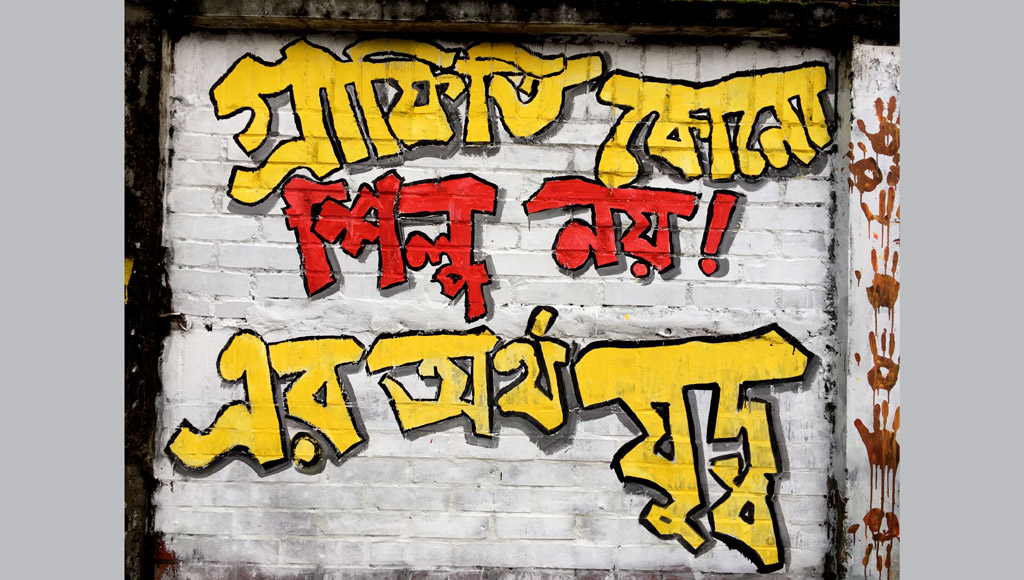

WHAT started as emancipatory self-expression was soon subjected to the dominant aesthetic regime. What started as ‘chika mara,’ a signifier of direct state repression, was soon turned into a sanctioned practice. But graffiti remains graffiti by virtue of its unsanctioned nature — the defiance and the subversive potential it carries and invokes. Its unauthorised writtenness materialises its affective emancipatory charge.

‘Step Down Hasina’ — stenciled or spray-painted — was already appearing on walls and streets long before the ‘Remembering Our Heroes’ event was declared as part of the 9-point demands. While rebellious phrases, verses, and slogans were painted, so were swearwords — the feared ‘f’ word or the sexist ‘k’ word — targeted at the ‘dictator’— a word that had de facto held a taboo status for the past 15 years. While wall art and murals created space for organised creativity that sought to channel the energy of resistance, the saboteur role was played by spontaneous spray paint bottles. Easily carried and used by people amidst curfew during a time of violent and deadly crackdown, many could not finish the phrases or lines, leaving them incomplete or longing for the end of dictatorship, perhaps in a bid to escape arrests or worse, the indiscriminate bullets targeting protesters.

The infrastructures that symbolised the authoritarian regime and deprived the people of public spaces were being reclaimed through symbolic reparations enacted via vandalism. The regime had long used development as a tool to justify its terrorising rule, seizing ownership of public spaces and infrastructures, alienating the people. The public rejection of the regime was being inscribed on the very structures that have long shielded the dictator. While students played with the signifieds of ‘rajakar,’ their affective core had been expressed through swearwords, long voiced by many of our marginalised siblings in tea stalls, transports and markets who defiantly charged their talk with affective coounter-violence. These are the very students who had chanted slogans against the police, questioning their worth back in 2018. They had the training and knew how to weaponise language — or rather, how language itself can act as a weapon. This time, slogans worked well and the reverberation led the students and the public to arche-writing.

They took up spray paint bottles to finally become the authors of their own history. The police and goons could clear the streets with tear gas, the bullets could shed blood, but they could not erase the hundreds of inscriptions declaring: ‘Ek dofa, ek dabi, shoirachar tui kobe jabi?’ Perhaps when speeches were gradually becoming impossible, arche-writing could be realised, breathing life into Derrida’s remark: ‘What cannot be said, above all, must not be silenced but written.’ The force of these writings was the force of collective consciousness, a binding agent that liminally invoked a revolutionary unity. Along with ‘ek dofa’ demands for the demilitarisation of the Chittagong Hill Tracts and ‘Kalpana Chakma Kothay’ also occupied space in public memory — an enactment of our national consciousness, with all its possibilities and pitfalls.

In a city where cosmopolitanism immediately translates into couthness, the Rangpuri dialect, written on metro rail pillars, serves as a disruptive force, a force that penetrates the regime of standardisation, which often fails to create resistance and demands servile gestures, or renders ineffective the creative force that a will for alterity can carry. It invites the audience to register the bereavement that envelops a call for justice against state violence, a maayer daak — ‘Hamar Betak Marlu Kene?’.

Although ‘Mo pobore hitte majjo?’ also demands justice for state violence, it is too ‘foreigned’ to be registered by the Bengali audience. While the Rangpuri dialect disrupts, the Chakma utterance ‘disgusts’. It is a call that demands silencing because, in the Bengali imagination, there is no room for the intimate others — the indigenous. Their indigeneity has been repeatedly denied, and attempts to inscribe their oppression on the walls of several districts in the Chittagong Hill Tracts have been actively censored by the Bengali civil-military complex, further asserting the presence of a colonial force that seeks to grab land and resources at the expense of these communities. Why does a question as simple as ‘Kolpona Chakma Kothay?’ require censoring, not just by the military but by ordinary Bengalis? Why are they so eager to smear the graffiti? Because it signifies the history of military-facilitated infiltration, tourism, resource extraction, and displacement, beginning with Bor Porong. Therefore, while Bengalis rejoice in the fall of a dictator, indigenous people are reminded of their exclusion from political liberation, and their lives continue to be marred by racial violence and displacement.

Back in the majoritarian plains, the affective charge that taboo lexemes carry had already been conjured to challenge the repressive regime, ‘Shoirachar Ch**’. However, their lack of political correctness has increasingly been questioned by the docile society of the dominant social order, often accusing them of reasserting existing sociocultural oppressions. The display of the public’s affective interior seems to unsettle mostly those who are part of this dominant order. But the intimacy created by the semantic link arguably acted as one of the driving forces of the uprising, also witnessed in the unparalleled popularity of ‘unhinged’ YouTube figures who frequently use taboo lexemes to frame their opinions. This semantic link between swearwords and repressive power can also be harnessed to challenge it, offering what could be termed cathartic swearing.

Perhaps one way to conceive the will of the people during the July revolution is to understand it as a will for alterity — new practices of selfhood. This will is expressed and materialised through a language that also enables this new self-expression. The words painted and stenciled on walls served as living testimonies of this self-expression.

However, once the final catharsis had been achieved on August 5, self-expressions were soon labeled obscene or profane, deemed too taboo to adorn the walls, gates, and pillars of public spaces. Many questions and swearwords were covered in white the day after the uprising by self-assumed ‘propagators’ of beauty and aestheticians who failed to recognise public graffiti as historical artifacts. In the Hill Tracts, the students encountered a different set of uniformed and ununiformed aestheticians who had repeatedly destroyed even concerted wall art after the uprising, leaving a clear message: history-making is not for the indigenous. While those painted words needed preservation, they were erased from public memory forever. It often escapes erasers that the power of graffiti lies in its liminality — the situational illocutionary force that has the potential to drive revolutionary change, as witnessed in Bangladesh.

Oliur Sun is a lecturer of English and Humanities at the University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh. He is a sunyatavadin and a creator/organiser of multidisciplinary knowledge in textual and visual forms based in Dhaka.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.