You can often learn just as much—if not more—by examining the downtrodden periods of a genre as opposed to only looking at the highs. So, after we ranked the best years in rap history earlier this week, it’s only right we rank the worst as well.

So what makes a poor year in rap, and how does it happen? Several factors contribute. Poor years often arise when rappers become obsessed with chasing trends, which leads to a dearth of innovation. They also occur when the leading figures hit creative cold streaks or stop competing altogether. Following an all-time great year can yield additional challenges. Then there are factors that artists or labels can’t control, such as the effects of death or generational global events that can disrupt entire industries.

When deciding on our ranking of the worst rap years, we weighted the quality of the music released that year and the significant moments—or lack thereof—that defined it, with a particular focus on patterns or outcomes that were detrimental to hip-hop. We didn’t consider any year before 1990—the year rap became a true commercial force—because the genre was still in its infancy, and it doesn’t seem fair to compare the early stumbles of a child to an adult. (Also, for the most part, the ’80s were awesome.) We also excluded 2024, as it’s not yet complete; however, transparently, this year would have been under consideration due to its disappointing releases. (Shout out to Kendrick Lamar vs. Drake, though.)

Here are the 10 worst years in rap history.

Complex original

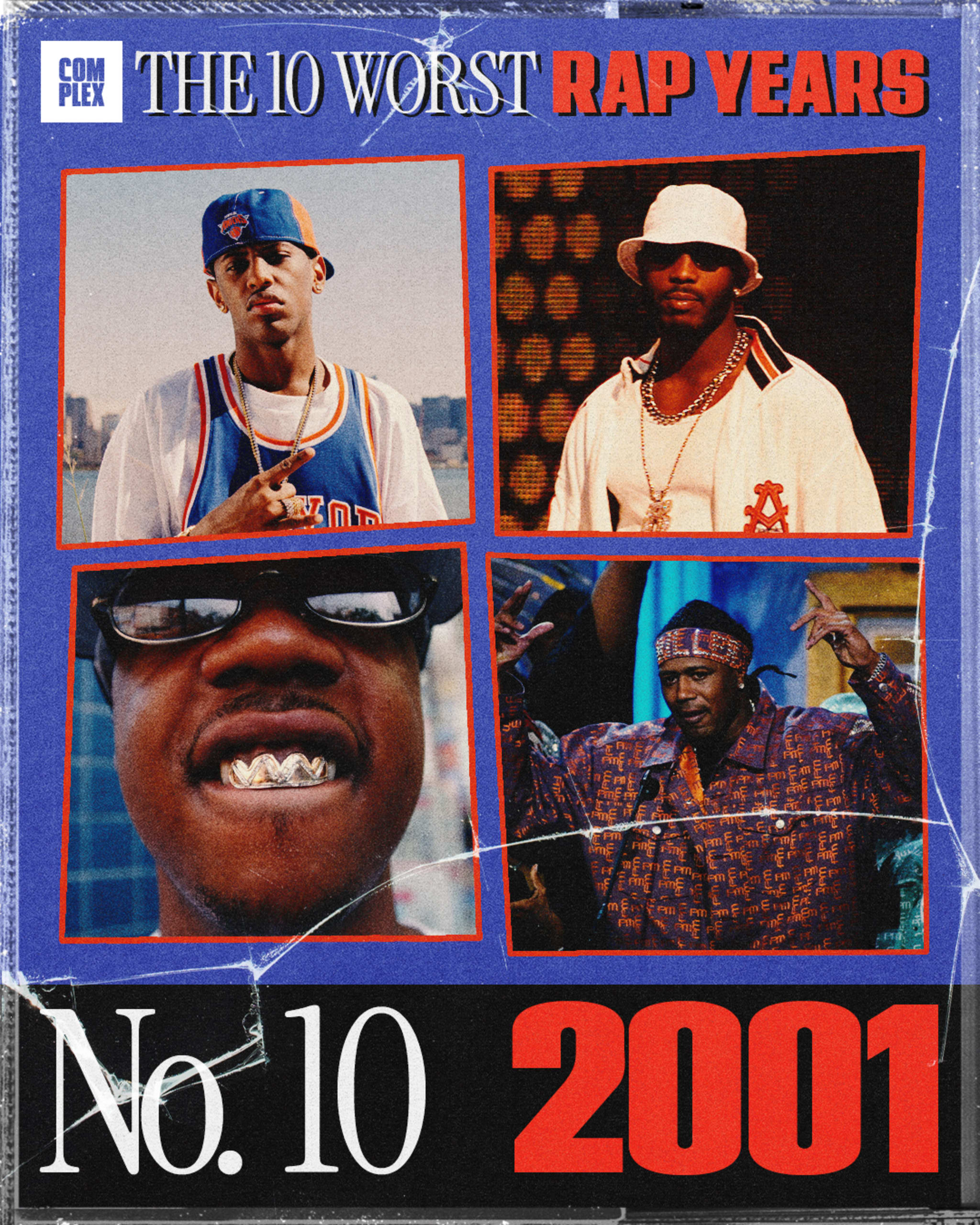

Why This is One of the Worst Years: Too manyrappers were trying to make commercial hits for the club and radio

A Silver Lining: Jay-Z and Nas faced off in one of the most memorable rap battles of all time

Baked into the lore of Jay-Z’s masterpieceThe Blueprint is its release date: 9/11. Less frequently mentioned is another significant rap release that day: Ghetto Fabolous. The debut album from Brooklyn rapper Fabolous is more representative of the year 2001 in hip-hop: The album features clever but empty raps and some notable guest appearances, but ultimately fails as a cohesive debut, functioning more as a scattershot collection of uneven club bangers.

As rap music became increasingly global after its late ’90s commercial boom, so did its sound. The year was hurt by the fact that there was a contrived effort by rappers to broaden their respective styles. Middle Eastern flutes (Nas’ “Oochie Wally”), Spanish guitars (Jay-Z and R. Kelly’s “Fiesta” remix), and Jamaican rhythms (T.I. and Beenie Man’s “I’m Serious”) were the dominant sounds on BET’s Rap City. This era was marked by a certain thirstiness that can be seen from even some of the most stubbornly hardcore rappers of the ’90s. Fat Joe started making club songs with R. Kelly, Mobb Deep was crafting love songs with 112, and Ja Rule entered his googly-eyed phase with Ashanti. It’s impossible to fact-check but this feels like the year when rappers started saying phrases like “I need a girl joint for the album.”

With The Blueprint, Jay-Z focused his efforts on a more classical, legacy-defining approach, tapping an in-house production team of Bink!, Just Blaze, and then-newcomer Kanye West to create a body of work that pays homage to the ’70s music he grew up with. This choice is part of the reason it was declared an instant classic upon its release. The other reason was that it seemed like the culmination of a long-simmering beef with Nas. This conflict—which officially popped off at Summer Jam in June, reached its creative peak with the release of “Ether” in early December, and ended later that month with Jay apologizing on Hot 97 for “Super Ugly”—almost makes up for what was a historically weak year for rap music. —Dimas Sanfiorenzo

Complex original

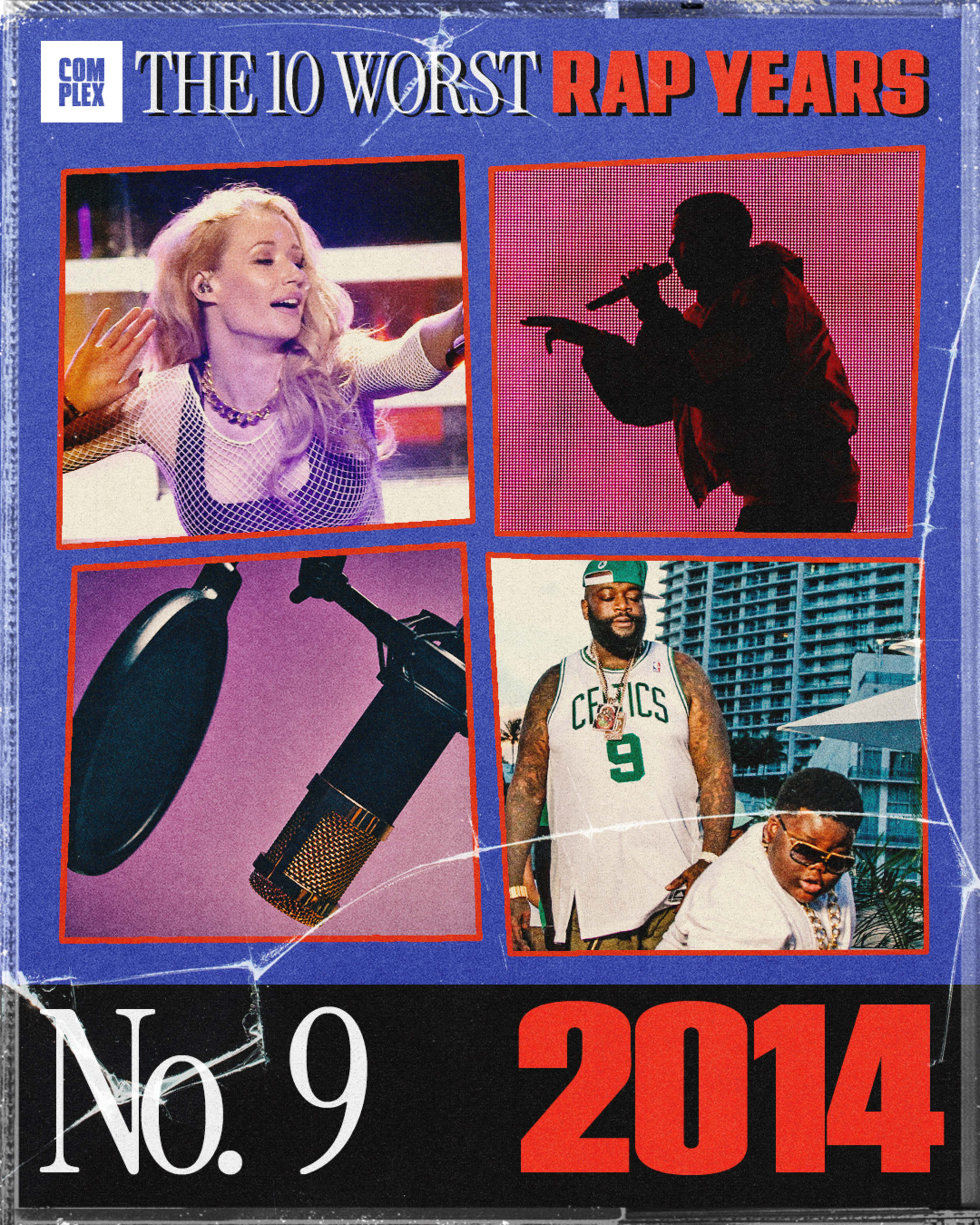

Why This is One of the Worst Years: A lack of music from the stars of the day while the next generation’s talent was still underdeveloped

A Silver Lining: Young Thug, one of the standout rappers of the 2010s, had his breakout year

Twenty-fourteen was a transitional period. The blog era was over, but hip-hop was still a couple of years away from dominating on streaming services. Pop-leaning rappers like Iggy Azalea thrived, while more street-oriented artists struggled to transition from mixtapes to albums. YG and Rae Sremmurd released great debut albums, powered in part by the ubiquity of their producers, DJ Mustard and Mike WiLL Made-It, respectively. Bobby Shmurda scored a viral hit, but by the end of the year he was embroiled in legal issues that would keep him locked up for years. Even Future, already well-established, stumbled when he tried to make a guest-heavy, industry-friendly album with Honest. In December, J. Cole and Nicki Minaj released hit albums that only underscored the relative lack of star power on the release schedule in the previous 11 months.

Young Thug was 2014’s breakout star, with hits like “Stoner,” “Danny Glover,” and “Lifestyle” running clubs and radio playlists. None of those songs ever appeared on an official album, however, which perfectly illustrates how frustrating music industry gridlock often was in 2014. Some of Thug’s career woes were unique to him—he’d aligned with so many labels on his way up that Atlantic, Cash Money, and 1017 Brick Squad spent most of the year squabbling about who Atlanta’s hottest rapper was signed to. In the meantime, Thug released collaborative mixtapes with Rich Homie Quan and Bloody Jay, but a proper solo album remained elusive for the time being.

Sometimes, there are just going to be years like this, when very little transcends and the music just feels a little undercooked. During an interview with XXL in October, ASAP Yams flat out declared 2014 as the worst year in rap music. So let’s finish this blurb with what he said: “It wasn’t any trends; musically it was a lot of dry-ass shit. Everybody [who] was supposed to drop, dropped the ball. This is probably the worst year of rap music ever. Let’s be honest.”—Al Shipley

Complex original

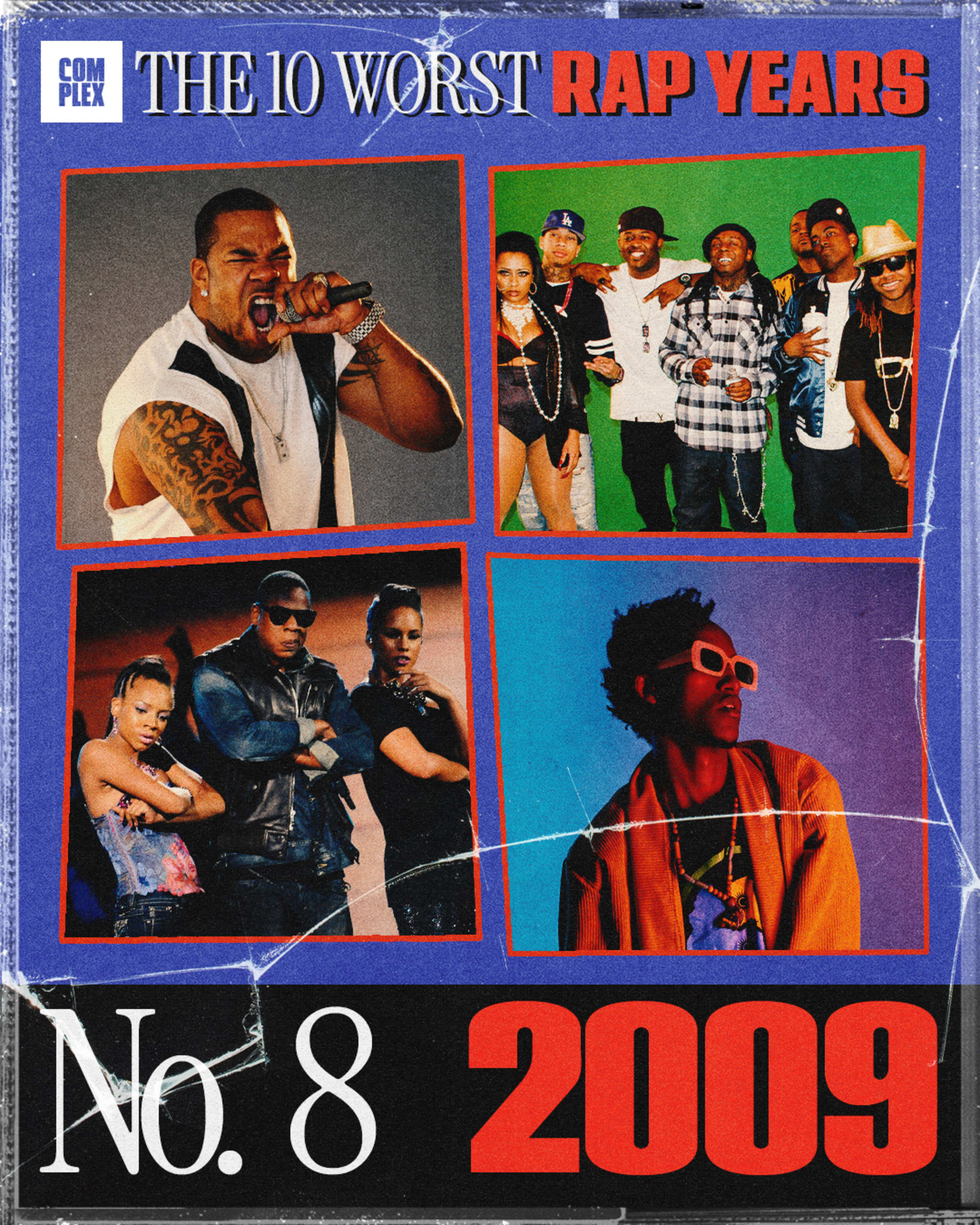

Why This is One of the Worst Years: It was overrun with bad sequels and cash grabs from rap’s elite

A Silver Lining: More interesting music was released in niche, underground spaces

Two-thousand nine was an undeniable lull in hip-hop, as veterans became caricatures of themselves and shifted into autopilot, focusing more on going viral than what made them great. A homogenization of sound washed over regions, particularly in the mainstream.

It wasn’t just subpar sequels like Jay-Z’s The Blueprint 3, Raekwon’s Only Built 4 Cuban Linx… Pt. II, Fat Joe’s J.O.S.E. 2, and Method Man and Redman’s Blackout! 2 that failed to live up to the beloved status of their classic predecessors. Anticipated new releases were met with lukewarm praise as well: Eminem’s Relapse, 50 Cent’s Before I Self Destruct, Busta Rhymes’ Back on My B.S., Clipse’s Til the Casket Drops and Fabolous’ Loso’s Way all felt flat. This was also a peak year for posthumous works that felt like money grabs, including projects from the estates of Ol’ Dirty Bastard and Lisa “Left Eye” Lopes. Even Dilla’s Jay Stay Paid felt somewhat forced.

In 2009, rap struggled to rebound from the end of ringtone rap’s brief rise. While ringtone novelty made millions for the likes of Soulja Boy, others faded into obscurity. Meanwhile, some of the genre’s most reliable artists dropped releases that sounded overly polished, trite, and predictable, taking all the wrong lessons from Ye’s Graduation by fixating solely on big hooks and catchiness, without much of the craft.

That said, 2009 did have notable exceptions. Some interesting music emerged from the indie, underground scene, like Yasiin Bey’s The Ecstatic, which has gained more esteem in recent years; MF DOOM’s Born Like This, a late-career masterwork; The Jacka’s street epic Tear Gas; and DJ Quik and Kurupt’s unorthodox BlaQKout. However, these gems were far too infrequent for what would go down as one of rap’s most desolate years. —David Ma

Complex original

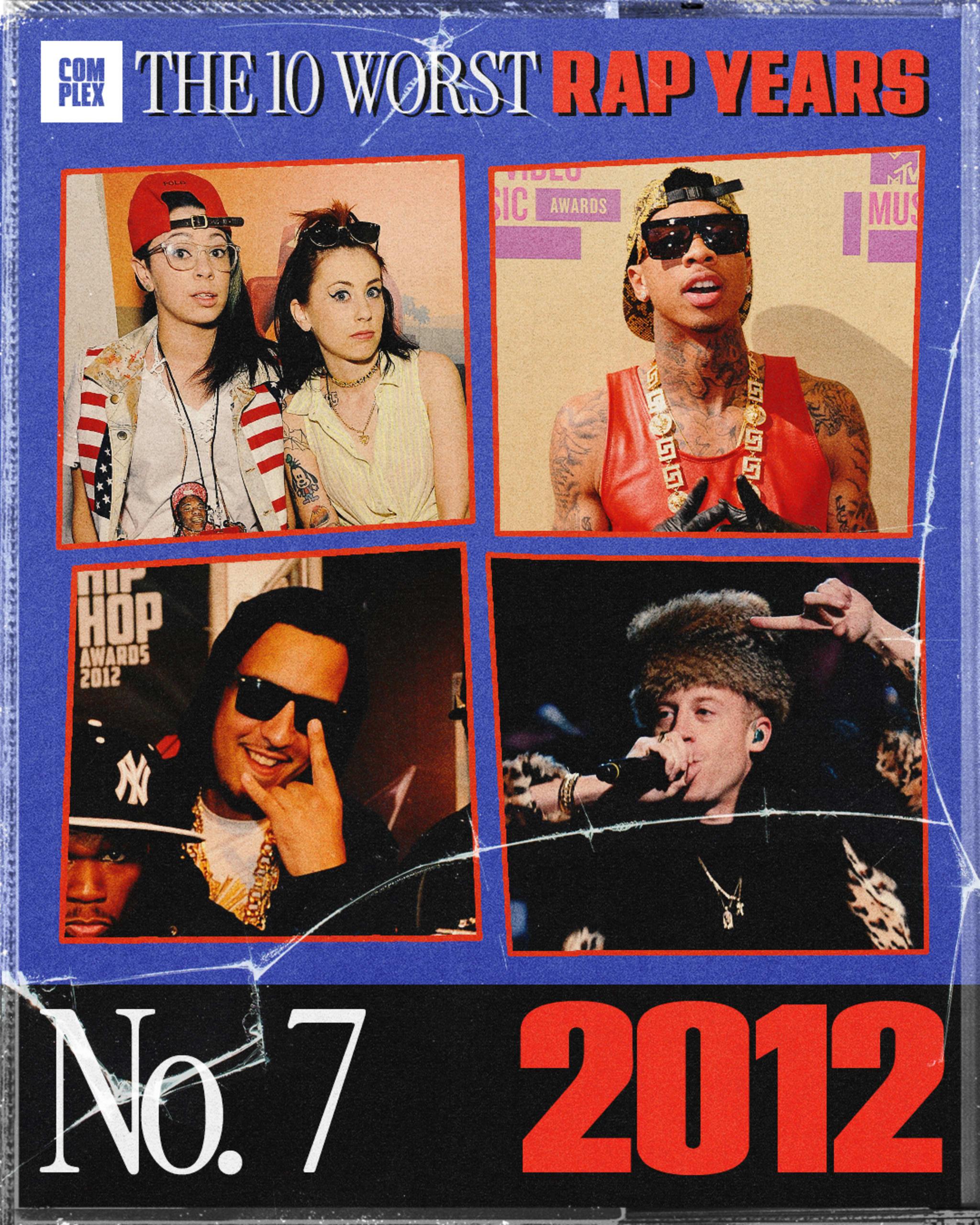

Why This is One of the Worst Years: Conservative rap releases dominated 2012, while newer sounds were marginalized

A Silver Lining: The rise of drill music and the release of one of the greatest rap debuts provided some bright spots

Sometimes, one great album can lift up a so-so year. But, conversely, in a so-so year, even a solid album can be perceived as an all-time great. Case in point: Kendrick Lamar’s good kid, m.A.A.d city, an album that benefited from being released during a mediocre year in rap music.

We look back at 2012 as the year of Chicago drill and the rise of Chief Keef, Lil Durk, and Lil Reese, who all signed to major labels that year. But the subgenre was not critically recognized outside of its core fanbase. In fact, despite the popularity of the music amongst young fans, much of rap media instead focused on the surrounding controversy and incriminating tweets, opening the door for the rap true-crime grift that exists now. While critics questioned the artistic merits of drill, they continued to glorify more traditional new rappers who offered their own versions of styles from earlier eras. Artists like Joey Badass, Action Bronson, Curren$y, Big K.R.I.T., and Freddie Gibbs rose to prominence—all worthy rappers in their own way, but also clearly inspired by (or derivative of?) artists from the ‘90s. In short, a lot of the shit that got attention was stale, while the more radical, and potentially more influential, music was marginalized. I should note that Kendrick also took a more traditional approach with good kid, m.A.A.d city, using narrative and West Coast-influences to craft an Illmatic-like classic. But at least his high level of rapping ability was matched by a knack for making anthems.

Kendrick was the high point, but there were other cool moments in 2012 that would resonate throughout the decade—the debut of tough-guy Drake on “Stay Schemin”, the last stand of Odd Future, 2 Chainz’s star-making summer, and Rick Ross’ attempts at turning MMG into a dynasty. Yet, none of it could make up for a year that just felt a little stale. —Dimas Sanfiorenzo

Complex original

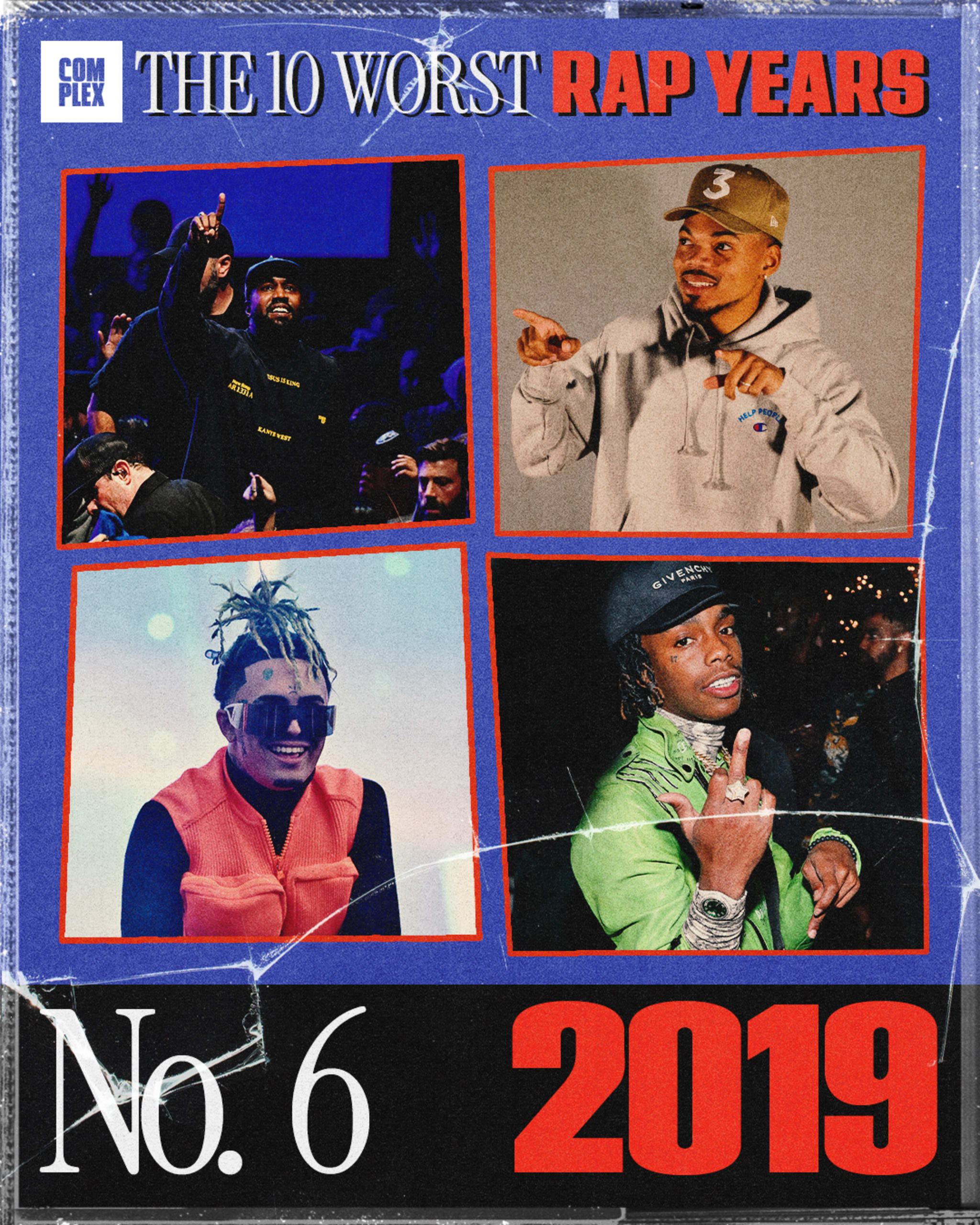

Why This is One of the Worst Years: Disappointing releases and the tragic deaths of stars in Juice WRLD and Nipsey Hussle

A Silver Lining: Cardi B becoming the first woman to win a Best Rap Album Grammy

For the most part, 2019 had all the characteristics of a forgotten year: None of rap’s Big 3 dropped albums. A rap GOAT did the equivalent of skipping an NBA season to play baseball, and the proverbial next up flopped. Second-tier rap stars thrived, but Atlanta’s melodic trap sounds were replicated to the point of oversaturation, and much of so-called SoundCloud rap fizzled out. Two-thousand nineteen is generally an afterthought, but tragedy made it indelible for the worst reasons possible.

In February, 21 Savage was detained by ICE for having an expired visa, followed by a series of ill-advised memes making fun of the situation. That same month, YNW Melly, one of Florida’s most talented young exports, was arrested for allegedly murdering both his friends and making it look like a drive-by shooting. He’s imprisoned to this day. A month later, Nipsey Hussle was shot and killed in the South Central LA plaza he’d spent his entire life trying to reclaim for his community. He was only 33.

In between the turmoil, good things still happened. Cardi B’s Invasion of Privacy won the Best Rap Album trophy at the Grammys. (She remains the only solo female to win the award.) With its intriguing genre-blending and eye for virality, Lil Nas X’s “Old Town Road” became the longest-running No. 1 in Billboard Hot 100 history. Tyler, the Creator released Igor. But, as he often had since 2017, Future hit cruise control with Save Me, an EP with some of the most forgettable tracks of his career. And, after unloading three acclaimed mixtapes and becoming a little annoying, Chance The Rapper stunted all of his momentum with Big Day, a middling album that somehow instantly convinced fans to lower their expectations for the would-be A-list torchbearer.

With a growing dearth of starpower, artists like Juice WRLD stood as proper bridges to the future, especially following the deaths of Lil Peep and XXXTentacion. But, days after his birthday that December, he died of an accidental drug overdose, cementing a year defined by loss and unfulfilled potential. —Peter A. Berry

Complex original

Why This is One of the Worst Years: Too much bleak end-of-the-world rap was released

A Silver Lining: MF DOOM debuted with a classic

“Four MC’s murdered in the last four years / I ain’t tryin’ to be the fifth, the millennium is here.”

This line from Mos Def’s “Mathematics” encapsulates the paranoid mindset of being a rapper in the late ’90s. The violent deaths of 2Pac, The Notorious B.I.G., Big L, and Freaky Tah from The Lost Boyz still loomed large as the 2000s approached. The atmosphere significantly influenced the music; hip-hop was in its pessimistic afrofuturism, Y2K stage: dark, moody, industrial, and often bare. It could be heard in the actual music, with rappers turning to synths and keyboards as harbingers of the future. But it was more apparent in the videos, which embraced a sci-fi aesthetic. To this day, we still talk in awe about the ways Missy Elliott and Busta Rhymes saw and explained the future. But this motif was all over rap in 1999, produced with varying degrees of success; artists like Nas, Jay-Z, Q-Tip, Method Man, and Diddy all explored millennium angst in their own ways, often utilizing corny CGI in the process.

With the end of the world looming and uncertainty about what the future would bring, some of rap’s stalwarts also started to mail it in. The fourth quarter of 1999 was a bloodbath, filled with underwhelming releases from Raekwon, the aforementioned Q-Tip and Nas, and even the God MC, Rakim.

However, there was also innovation in 1999. KMD’s Zev Love X reemerged as MF DOOM, cleverly flipping cheesy ’80s quiet-storm sounds into lo-fi hip-hop classics. A rough-around-the-edges rapper from Memphis, Project Pat, made his national debut, inventing flows that baffled Northerners but would leave a lasting impact decades later. Prince Paul created the first rap opera (A Prince Among Thieves), telling one cohesive story across an album long before Kendrick perfected the format. Meanwhile, Dr. Dre redefined the rap blockbuster with 2001, which helped propel Eminem into a superstar, leading up to the release of the The Marshall Mathers LP in 2000.

As it turns out, all the worry was for naught—rap would live to see another day. —Dimas Sanfiorenzo

Complex original

Why This is One of the Worst Years: Goofy ringtown rap was everywhere

A Silver Lining: Kanye West’s Graduation outselling 50 Cent’s Curtis was a standout

Look, Nas was deep in his old-head bag when he dropped a whole-ass album called Hip-Hop Is Dead at the end of 2006. The concept was gimmicky and overwrought—try listening to “Who Killed It?” without laughing. By his own account, the whole idea was reductive. But—but—he low-key had a point, and 2007 serves as a comprehensive validation. Tacky, yet somehow also indistinct, 2007 was a drab slice of shameless trend-chasing and rote commercialism. Ringtone rap was just about as big as it would ever be; gangsta rap started to lose some of its luster; and for every A-list blockbuster, there was an accompanying dud, sealing the year’s fate as a net loss for the culture.

The issues were multilayered. Soulja Boy wasn’t the problem; everyone wanted to Superman that hoe. The problem was that for every “Crank Dat,” there were three or more shittier versions. Remember V.I.C.’s “Get Silly”? If you don’t, be grateful—and if you do, I don’t need to go any further. These copycat tracks felt like mindless AI before there was mindless AI. By the time gems like Jay-Z’s American Gangster and Lupe Fiasco’s The Cool dropped toward the end of ’07, the year was already lost, with grim shit like MIMS’ “This is Why I’m Hot” and Shop Boys’ “Party Like a Rockstar” dominating the year in radio.

There are many florid adjectives I could use to dissect the year, but it’s easier to cut it here: 2007 just wasn’t it. Yes, Ye dropped Graduation, defeating 50 Cent and his pandering Curtis LP in the process, but snap rap was a sound we had yet to completely graduate from. There was just too much superficial newness—too many lame dances. Score this one for the old heads.—Peter A. Berry

Complex original

Why This is One of the Worst Years: Syrupy pop-rap became the main sound of commercial hip-hop

A Silver Lining: Landmark debuts from Ice Cube, A Tribe Called Quest, and Brand Nubian

In 1989, DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince won the first Grammy Award for Best Rap Performance, which theoretically set the tone for what became the commercial-rap explosion of 1990.

The win was ironic (and inevitably challenged by other artists), since 1989 is right in the middle of rap’s golden era, and a slap in the face to the creative and important groundwork being laid by groups like EPMD, De La Soul, Public Enemy, and many others. Critically speaking, that Grammy win gave everyone the wrong idea of the edge to which hip-hop can be pushed. That’s not to say that both Jazzy Jeff and Will Smith didn’t evolve into titans of both hip-hop and Hollywood, but it’s what their Grammy win signified to every Tom, Dick, and Rob Van Winkle.

From “Ice Ice Baby” to MC Hammer’s “U Can’t Touch This”, all of the progressive breakthroughs in rap were overshadowed by jingles and dance routines. Artists who were fighting against social injustice—addressing the crack era, police brutality, the AIDS epidemic, and speaking up for women’s rights—were mostly muted by this poppier interpretation of a culture that originated at street level. It was almost as if this became a welcomed distraction by the masses, who neither wanted to hear nor address the ills being documented in rap’s rhyme book of record. Little did we know that this would only be the start. The year 1990 gave us a glimpse of the shape of things to come once hip-hop landed in the wrong hands. —Kathy Iandoli

Complex original

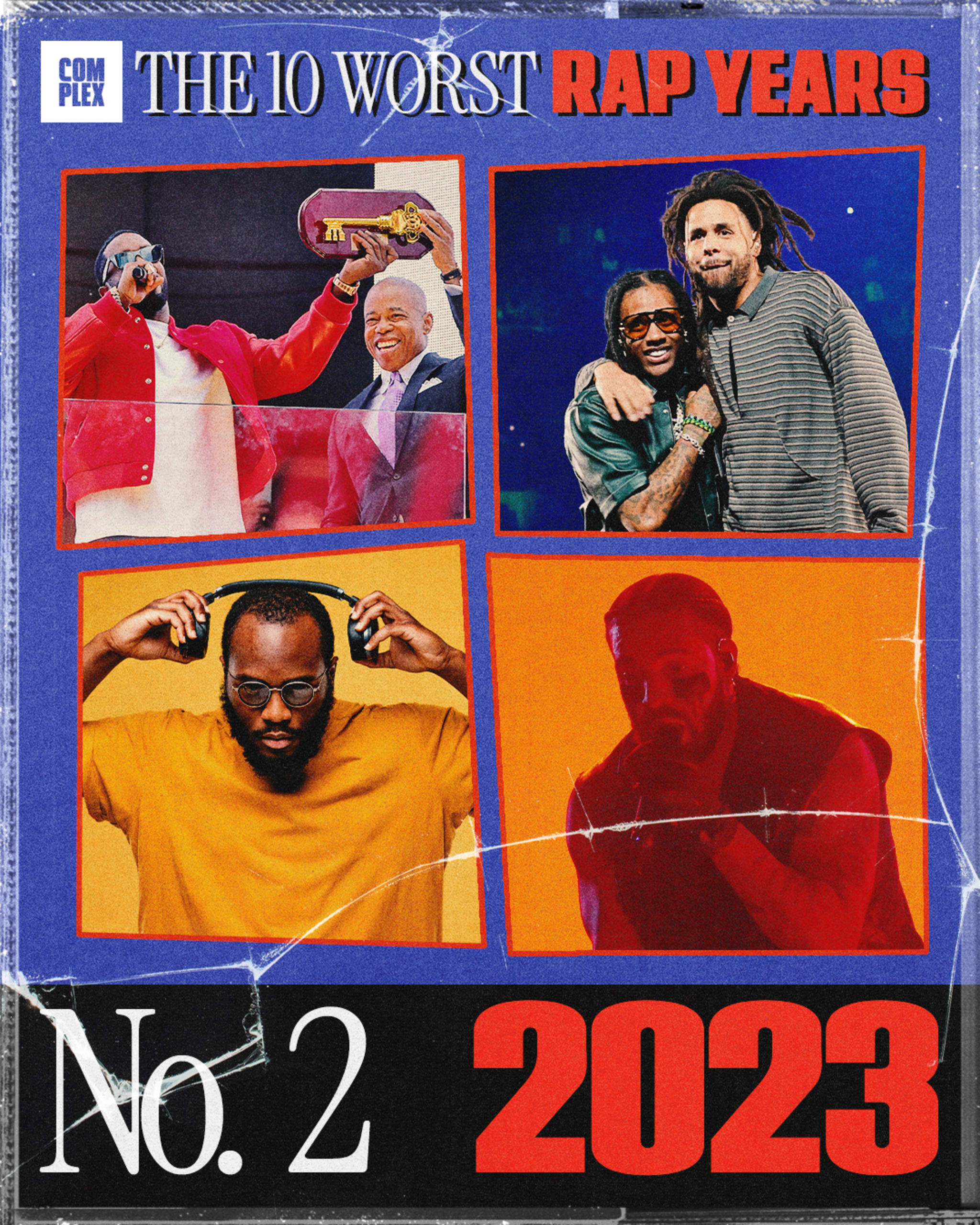

Why This is One of the Worst Years: The spotlight was on hip-hop for its 50th year, which highlighted how much of a slump the genre was in

A Silver Lining: The joy of seeing hip-hop get flowers all year for its 50-year anniversary

An auspicious 1973 block party hosted by DJ Kool Herc in the Bronx has been hailed as the unofficial birth of hip-hop culture. And 2023 was packed with all-star celebrations of hip-hop’s 50th anniversary, including a special Grammys medley and a concert at Yankee Stadium. Throughout 2023, however, fans and artists alike couldn’t help but notice that the genre was in a commercial slump, and arguably a creative one.

For the entire first half of 2023, no rapper scored a No. 1 song or album on the Billboard charts. Lil Uzi Vert broke the Billboard 200 drought in July with the Pink Tape, while no rapper topped the Hot 100 as the main artist on a song until Doja Cat in September with “Paint the Town Red.” Flimsy hits by Jack Harlow and Ice Spice crossed over, while established stars like Drake, Travis Scott, and Nicki Minaj dropped albums that felt like business as usual instead of exciting new chapters. Even an attempt at a meaningful crossover hit, Lil Durk and J. Cole’s “All My Life,” was too saccharine, and tainted by its association with disgraced pop hitmaker Dr. Luke.

Atlanta’s bustling and highly collaborative scene had carried mainstream hip-hop through several years over the past two decades, but morale seemed especially low in the city in 2023. The 2022 death of Takeoff was followed by a feud between his Migos groupmates Quavo and Offset, and the state of Georgia commenced a racketeering trial against Young Thug and YSL Records. Lil Yachty, who took a vacation from rapping with the acclaimed psychedelic rock album Let’s Start Here, became one of the most outspoken critics of the state of the rap game. But there seemed to be fingers pointed in every direction, as if everyone was a little responsible for hip-hop’s disappointing golden anniversary year. —Al Shipley

Complex original

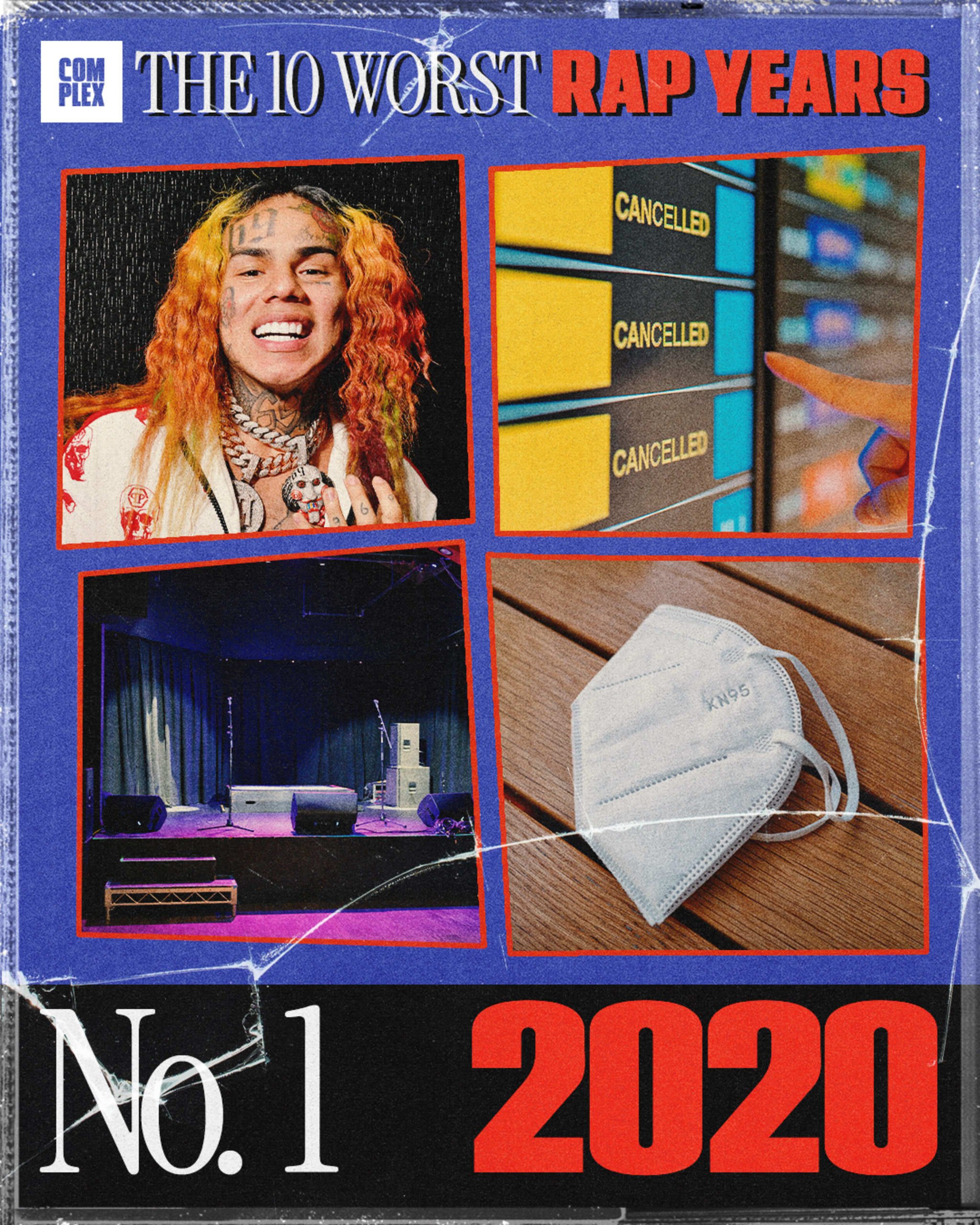

Why This is One of the Worst Years: Pandemic shut everything down, meaning no new releases and no new venues to enjoy the releases

A Silver Lining: Rap artists showed how they could adapt, creating new platforms like Verzuz

I’m just going to be blunt here: 2020 was pretty ass on all fronts, not just in rap, but because of a pandemic that shut down the entire world. If the best years in rap are remembered by what was happening at the time and the palpable energy that could be felt in the genre, then 2020 is the absolute worst year in rap history; artists weren’t able to leverage their music, so most just gave up on releasing anything of consequence. It was a barren time, with the best rap albums that year—Lil Baby’s My Turn, Lil Uzi Vert’s Eternal Atake, and Jay Electronica’s A Written Testimony—coming out literally weeks before the COVID-19 shutdowns took place. Pop Smoke’s Meet the Woo 2 tape was released in February, in part to set up his forthcoming full-length major label debut. But he was killed less than two weeks later, a devastating loss that was really felt when “Dior” soundtracked the George Floyd and Breonna Taylor protests around the country later that year.

Hip-hop is resilient, though, and despite government mandates forcing venues to close, artists still found a way to engage with fans and push their art using social media. This did spark some cool shit: DJ D-Nice’s Instagram sets provided us moments of connection, and of course there was the birth of Swizz Beatz and Timbaland’s Verzuz franchise, which became an important vehicle for legacy acts to show off their impressive discographies. (The debates about who would win hypothetical battles were fun for a while.) But it could never replace the real thing. And, in fact, we saw Verzuz peak a year later when it embraced a live-concert format rather than something we only watched on the ’Gram.

Then there was TikTok, one of the few big winners of the pandemic. The platform gained crazy traction in rap and artists began to see the commercial benefits of blowing up on your FYP. This led to some entertaining trends, like the “Savage” dance that came from Beyoncé and Megan Thee Stallion’s massive remix—but also some really wack ones, like Drake trying to manufacture a trend with the “Toosi Slide.”

The app also opened up a new can of worms: It accelerated a content-first, music-second strategy that many rappers now follow. We still see the effects today, with artists oversharing their day-to-day lives on social media instead of engaging with their audience in more meaningful ways. In fact, I would argue hip-hop has yet to fully recover from the pandemic. The pricing of concerts is wacked, with price gouging hurting fans while most recording artists can’t afford to make a living touring. Add that to the fact there has been fewer new stars breaking out, with fans struggling to differentiate between the signal and the noise in this new post Covid “content” era we’re in. Two thousand and twenty was easily the worst year for rap. Now the question remains…when will we start to recover? —Jordan Rose

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.