Anyone who has attempted to define hip hop- to peg it down and domesticate it- has been met with the same challenges as those who try to do the same with horror and the Gothic. Hip hop, like horror, is not merely a genre but an artistic modality born of transgression. One thing is taken apart and transformed into something altogether new and right for its discursiveness.

In this way, it’s easy to draw comparisons between the founders of hip hop- DJ Kool Herc, Grandmaster Flash, Afrika Bambaataa, and DJ Disco Wiz- and Dr. Frankenstein. If we think about an album, a song, a sound as a kind of sonic body, they were snatching records, chopping up songs, sampling sounds, and remixing them into something else entirely that became the future.

There’s an inherently gothic nature to Black art that exists beyond genre, subject, aesthetic, or intent by fact of the history and conditions of Black life. Like the field songs and spirituals, the Blues, jazz, and rock, hip hop was born of these conditions. It blossomed from the cultural revolution of the ’60s, the advent of new technology, and pure inventive genius on behalf of the originators of technique.

Composed of sonic traditions as well as oral and literary traditions from across the diaspora that can be approached hauntologically, where the haunting is both method and form. Songs haunted by (or in communion with) samples of other songs. Rap as weaponry, as the battleground for more cultural and actual warfare than perhaps anyone ever imagined and through which particular histories of time and place occur. So it’s not enough to say hip hop’s cultural roots run deep. You have to account for the blood in the soil.

Though their influences long precede them (here’s lookin’ at you, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins), punk, hip hop, and modern horror all emerged simultaneously but incongruously out of the same moment from the late ’60s through the mid-’70s. While genre heavyweights like Halloween, The Exorcist, Jaws, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and Alien broke box office records, blaxploitation films like Blacula, Foxy Brown, Shaft, and Sweet Sweetback’s Badassss Song were also raking in giant profits based on the appeal of their predominantly Black casts, who Black audiences were starving to see.

Understanding that these were the films folks were watching- which is to say nothing of the diaspora’s long tradition of storytelling about the supernatural– it’s no wonder that horror and its adjacent themes and motifs have been present in hip hop pretty much from the beginning. In fact, the blaxploitation boom arguably prophesied what was to come for hip-hop once the ghouls of industry came knocking. Let this be your annual reminder that the “exploitation“ in “exploitation filmmaking“ refers to the economic models behind production and distribution—it does not merely refer to character tropes.

Blaxploitation films were distinguished by miniscule budgets (which led to shoddy scripts and dangerous working conditions) and short theater runs that nevertheless saw millions in returns on investment for white-owned and operated production and distribution companies. There’s no significant distinction to be made between the film and music industries on this matter, nor does it really matter at the end of the day if the one doing the exploiting is white or Black. The horrors persist in the architecture.

But I digress. The earliest iterations of what we’ve come to call horrorcore emerged during the hyper-conservative Reagan ’80s. After the blaxploitation boom of the ’70s, Black folks’ presence in mainstream horror films had dwindled to tokens, sidekicks, and villains; roles that, underneath the modern veneer, more closely resembled the spooks, servants, and monsters of the ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s in terms of their narrative function. But as the Moral Majority’s influence spread and our presence in Hollywood diminished, horror’s presence in hip-hop expanded.

Rap is, first and foremost, a literary medium. Before the existence of the written word, poetry, oral storytelling, and song bore no distinction; their content was a composite of myths carried by individuals as they moved from place to place. All lyricism is an extension of this prehistoric human practice, but rap transforms this predisposition toward myth-making into an Olympic sport.

One of Afrofuturism’s most recognizable conceits revolves around outer space as a frontier of wonder, terror, and most importantly, possibility. Since the ’50s, no single artist has encapsulated these ideas more completely than Sun Ra, whose innovations in music, performance, and philosophy coalesce around the personal mythology that he was an alien from Saturn guiding us into harmony with the broader universe. On “Adventures of Super Rhyme“ (1980) Jimmy Spicer raps “No, I didn’t come from the planet Earth/ Planet Rhymeon is my place of birth… my father put me on a meteorite/ sent me to Earth to rock the mic.“

Spicer uses the same conceit as Ra to vastly different effect, spinning a kind of romance about being destined to become an MC. Naturally, this means meeting a monster or two along the way. His Dracula isn’t the one of Stoker’s imagination though—this one “didn’t like blood, not this vampire/ the disco beat was his desire,“ delivered in Bela Lugosi’s famous Transylvanian accent. Four years after “Adventures of Super Rhyme,“ The Brother From Another Planet crashed into theaters.

Once “Thriller“ opened the floodgates and fundamentally reshaped the relationship between music and movies in 1982, hip-hop artists increasingly drew inspiration from the horror genre. In 1986 Dana Dane sampled Jack Marshall’s iconic theme from The Munsters on “Nightmares,“ a song in which he likens women to “beasts“ and “creatures,“ i.e. the source of said nightmares, and casts Black women for these roles in what amounts to a perfect case study of the ways misogynoir has been present in hip-hop culture since its inception. The same year “Nightmares“ was released, Grace Jones- with seven studio albums under her belt- gave her unforgettable performance as the voiceless Katrina in Vamp.

Two years later, The Geto Boys released Making Trouble which would prove wildly influential on horrorcore and adjacent subgenres to come. That same year, Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince released “A Nightmare On My Street,“ Insane Poetry put out their first single “Twelve Strokes To Midnight“ which samples the theme from Friday The 13th, and The Fat Boys’ “Are You Ready For Freddy?“ became the official theme song for A Nightmare On Elm Street 4: The Dream Master. By the decade’s end, the unholy union of hip-hop and horror had fully commingled, setting the stage for the veritable deluge of projects that emerged throughout the ’90s.

In the same way that horror and crime mysteries both have their roots in the Gothic, horrorcore is intimately tied to gangsta rap, sometimes representing the extreme of a subgenre already maligned for its extremity. Pioneers like The Geto Boys, Brotha Lynch Hung, Insane Poetry, Ganxsta N.I.P, Esham, and Kool Keith all used the motifs, narrative techniques, themes, and sonic landscapes of horror to narrate the tensions that made up the harsh realities of Black life. When the individual comes up against predetermined structural marginalization, poverty, addiction, police brutality, and racially gendered generational violence, it isn’t altogether distinct from a brush with the supernatural.

Notably, these artists frequently prescribed monstrosity to themselves, developing personas or narrating stories about their own lethal nature; a trend that has never ceased but ceaselessly inspires an ire that transcends political affiliation. Hip-hop in general, and gangsta rap/horrorcore in particular, have always triggered outrage discourse heavily fueled by respectability politics and satanic panic-esque hysteria, just like horror films.

And just like horror films, they have the capacity as art forms to reveal the complexities and paradoxes of the human condition in ways that titillate and repulse. By revealing the dark underbelly of the status quo, they thus reflect and raise questions that prohibit these modalities from ever really becoming mainstream precisely because their violence is emblematic of the truth of the mainstream.

The ’90s demonstrated this in a major way. Geto Boys, Gravediggaz, Flatlinerz, Three 6 Mafia, Bone Thugs-N-Harmony, and Insane Clown Posse emerged from the underground to fully establish horrorcore as a distinct subgenre. Balancing the sillier camp aspects of proto-horrorcore and gangsta rap’s harsh preoccupation with violence while retaining a poet’s control of language and a certain gallows humor, this generation really harnessed horror and hip-hop’s respective powers to plunge the depths with profundity and misogyny in equal measure.

At the same time, Black filmmakers were exploring similar themes through horror films. Gravediggaz reflects on religion, theology, and morality through their work just as James Bond III, the writer, producer, and director of 1990’s Def by Temptation did, albeit in very different ways.

It’s no wonder, then, the slippage that occurred between music and film. When I wrote about Megan Thee Stallion’s Cobra Era, I discussed horror’s role as an oft-relied upon bridge for artists as they narrate their gradual evolution, but it’s also been a bridge between different facets of industry.

Behind the cinematography for the 1992 Tupac-led crime thriller, Juice was long-time Spike Lee collaborator Ernest R. Dickerson, who would go on to cast and direct Jada Pinkett as the first-ever Black Final Girl in 1995’s Tales From The Crypt: Demon Knight. Rusty Cundieff’s iconic anthology Tales From The Hood was released that same year, but his first feature in 1993, Fear Of A Black Hat, was a hip-hop mockumentary in the spirit of This Is Spinal Tap.

Then there were the music videos. Geto Boys confront their deepest anxieties in the unsettling “Mind Playing Tricks On Me.“ Busta Rhymes cultivated a uniquely Gothic Afrofuturist aesthetic that is, to this day, entirely his own. Snoop Dogg’s 1993 video for “Murder Was The Case“ featured his dealings with the devil.

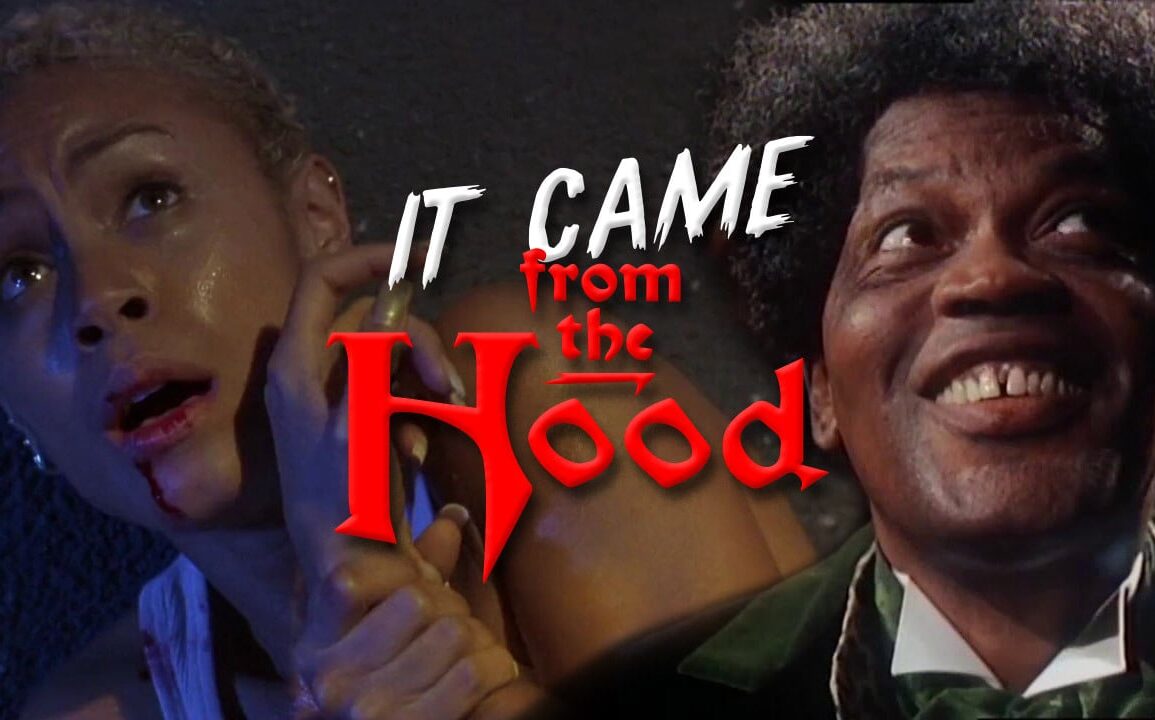

But once Ice Cube starred alongside Jennifer Lopez in 1997’s Anaconda, not a year passed for almost a decade that didn’t see at least one horror movie cast a hip-hop/R&B star, be it LL Cool J in Halloween H20 and Deep Blue Sea ), Snoop Dogg in Urban Menace, Bones, and Snoop Dogg’s Hood of Horrors, Brandy in I Still Know What You Did Last Summer, Ice T in Leprechaun in the Hood, Coolio in Dracula 3000, Aaliyah in Queen of the Damned, or Will Smith in I Am Legend.

It wasn’t until the end of the 00’s00, though, that horror and hip-hop next converged in a culture-defining way, and it started with Kanye West interrupting Taylor Swift’s acceptance speech at the 2009 MTV Video Music Awards. 2010’s My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy was West’s response to the sweeping condemnation that followed this moment, and with it, the highly controversial music video for “Monster.“ Featuring an all-star lineup alongside West, including Rick Ross, Jay-Z, Bon Iver, and Nicki Minaj in what would come to be a career-defining moment, the video chock full of monsters and dead models- stoked feminist outrage, ended up being banned from MTV, and was pulled from YouTube.

It’s worth mentioning that RZA, otherwise known as The RZArector while with Gravediggaz, is a co-producer of My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy. Kid Cudi was also featured, an appearance that followed West signing him to his GOOD Music label in 2008 after the success of his debut single “Day n Nite.“ A decade later, this partnership evolved into Kids See Ghosts, a project emblematic of and concerned with the artists’ respective struggles with mental illness that often conjures a sonically psychedelic eeriness.

Over the span of his career, Cudi retained the Geto Boys’ penchant for using horror’s lexicon to confront the demons that dwell within, his work grappling with themes of alienation, shame, party culture, sex, and ambition over electro beats and samples from indie and psychedelic rock bands. Following Cudi on the come up was The Weeknd, who doubled down on this method to produce the darker, moodier, “haunted strip club“ vibe we’ve come to know and love.

Of all the contemporary artists in hip-hop and R&B who nod to horror, The Weeknd perhaps most notoriously incorporates it as an enduring core element of his artistry. Direct references to the horror genre are imbued in everything from 2013’s Kiss Land, which he described as a Carpenter, Cronenberg, Scott-influenced “horror movie“ so-named because “if you watch a horror movie and it’s called Kiss Land, it’s probably going to be the most terrifying thing you’ve seen in your life,“ to 2020’s After Hours, which came accompanied by a visual album that functioned as a serialized horror feature.

Since then, The Weeknd has released two additional albums, become the first pop star to be featured on the cover of this here magazine, and gone on to transform the world of his music into a living nightmare at Universal Studio’s Halloween Horror Nights while acting like a living nightmare on HBO’s The Idol, a project he co-wrote alongside Assassination Nation and Euphoria’s Sam Levinson. Kid Cudi too fomented an acting career alongside his career as a musician, having appeared in episodes of Shudder’s Creepshow, Westworld, as well as Ti West’s X and most recently, as the delightfully cunty diva-rapper, The Thinker, in M. Night Shyamalan’s Trap.

Horror is ubiquitous among women in hip-hop. Rihanna hit a nerve (or several) with her 2015 vengeance fantasy, “BBHMM,“ in which Hannibal’s Mads Mikkelson stands in for her doomed and dastardly accountant. Beyoncé’s visual album for Lemonade is a master class in Black women’s Southern Gothic.

Megan Thee Stallion has consistently paid homage to horror’s greatest monsters and heroes through her cosplay, music videos, and general creative direction, and has let it be known since 2019 that she’s working on a horror script. Be it something she produces herself, a supporting role à la the ’90s-’00s, or the starring role (Megan Thee Final Girl, hey!), it feels inevitable we’ll see Thee Stallion onscreen at some point in the not-too-distant future.

Doja Cat, too, has made elements of horror and the weird a major aspect of her creative direction. And perhaps most recently, Doechii has waded into the swampy depths of the Southern Gothic and come out having crowned herself the Swamp Princess (or Ruler, depending on where you heard it). Watch out for the gators.

Then there are artists like Rico Nasty, Janelle Monae (who has her own haunted manor at the LA Haunted Hayride), Lil Uzi Vert, Odd Future, FKA Twigs, Lil Nas X, and so many more who similarly draw influence from the genre in a vast multitude of ways, while newer subgenres like trap and drill evolve horrorcore for a new generation. However you may feel about it, horror is deep in the blood of hip-hop and hip-hop is frequently a horror film expressed through a different medium.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.