The origins of Rap (rhythm and poetry) trace back to the early 1970s in the United States. With the globalization of culture, the genre has spread worldwide, adapting and evolving by incorporating diverse cultural aspects, which made it even richer. In the 1980s, rap reached São Paulo, and, in the last decade of the 20th century, its lyrics took on a more critical tone. Associated with the peripheries and marginalization, rap became a form of protest against social contradictions and inequality.

From the 2000s onwards, the genre underwent significant changes, occupying unprecedented social spaces and experimenting with new aesthetic elements.

These transformations are the focus of a research project by Professor Daniela Vieira dos Santos from the Department of Social Sciences. The project “The New Condition of Rap in Brazil” builds on her postdoctoral research at the University of Campinas (Unicamp), completed in 2019. Professor Daniela describes this period as one of “great learning”.

A professor at UEL since 2020, Santos started the research project based on the many developments her postdoctoral research unveiled. The most significant changes were observed starting from 2010, although the first ones date back to the 1990s, as she explains. However, despite these changes, the studies revealed that these findings are not about “new generations” of rap, but rather a different category: the “new condition” of rap.

Rap in Brazil, which initially had more limited reach within certain social groups, has expanded in this century, gaining greater visibility and recognition nationwide. Nowadays, it is legitimized not only in the peripheries but also crosses borders, with Brazilian rappers going on international tours and recording in other countries. Moreover, the themes addressed in rap lyrics that once focused on issues of urban peripheries, such as poverty, now include identity issues, like sexual orientation. “Rap was born sexist, but that has already changed”, notes the researcher.

Thus, the genre, which initially had a limited audience, has expanded. Young people from different social classes and backgrounds began to appreciate it. Rap’s increased presence in the media and other spaces, such as bookstores, contributed significantly to this growth, characterizing its new condition. Additionally, Professor Daniela attributes part of this “new condition” to the political context of the Lula and Dilma governments, which supported rap and other previously marginalized cultural expressions.

Aesthetics

Aesthetically, rap is characterized by its flow, combining rhythm and rhymes. In the 1990s, sampling — combining mixing segments from different songs — became very common. These samples often came from other genres, such as pop or even classical music. An example is “Prince Igor” (1997) by American rapper Warren G., featuring Norwegian soprano Sissel Kyrkjebø, who sings excerpts from the opera “Prince Igor”, and unfinished work by Russian composer Alexander Borodin, who died in 1887.

The new condition of rap may not be as sample-heavy as in the past, but it has introduced fresh aesthetic elements, continuously innovating and creating what Professor Daniela describes as a “musical library” within each song. She sees this evolution as rich, powerful, and educational for listeners, as it fosters dialogue and offers new interpretations of music. According to the researcher, current concerns are to avoid repetition and to experiment with something different.

Racionais MCs and Emicida

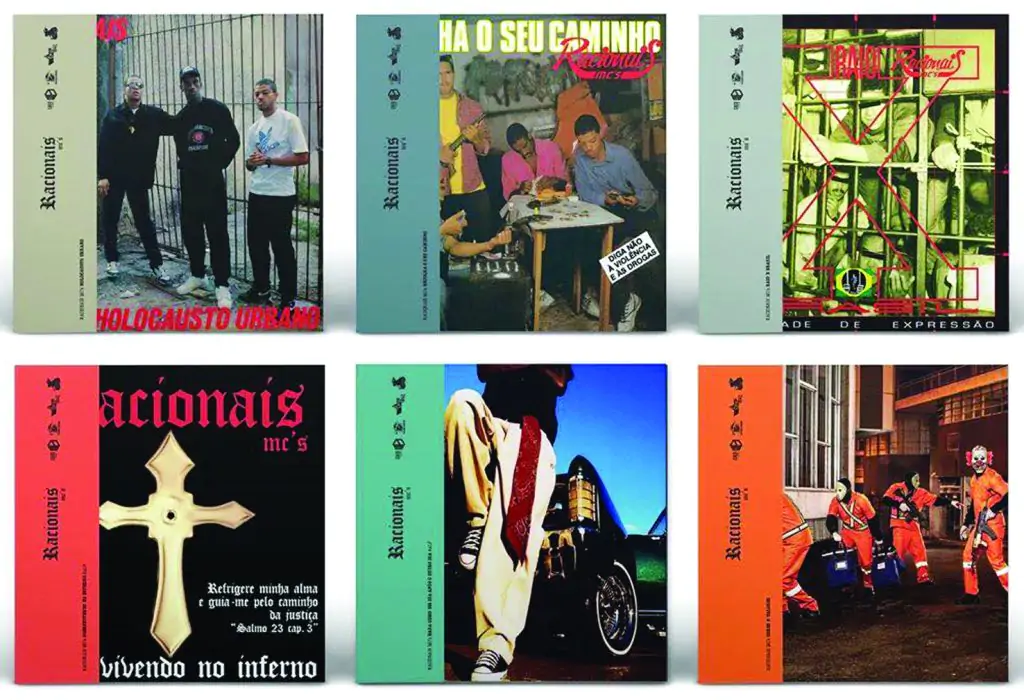

It’s impossible to talk about rap in Brazil without mentioning some important names, Professor Daniela emphasizes. Two of them are Racionais MCs and Emicida. Racionais MCs, formed in São Paulo in 1988, are one of the main references for the genre in the country, influencing generations of artists and gaining international recognition. Considered by many the “father of Brazilian rap”, the group stands out for its strong beats and powerful lyrics that directly address social issues.

Their songs, especially those from early albums, denounce issues such as racism, poverty in urban peripheries, police violence, drug trafficking, government neglect, and organized crime. The song “Diário de um Detento” (1997) (Diary of an Inmate), for example, is based on the notes of a former inmate of Carandiru prison, where a massacre in 1992 resulted in the deaths of 111 prisoners. With a documentary-like feel, the music video won two MTV awards and was ranked the second-best video of all time in a list published by Folha de S. Paulo in 2012.

Leandro Roque de Oliveira, known as Emicida, is regarded as the standout artist of the 2000s. His stage name originates from his numerous victories in freestyle battles, where he would “kill” his opponents with his rhymes, earning him the nickname “MCcida”, later adapted to “Emicida”, combines “MC” with “homicida” (Portuguese for “homicide” or “killer”), playing on his reputation as a “lyrical slayer” of rivals in the rap scene.

According to the researcher, Emicida is a typical representative of rap’s new condition: more professional, with more flexible (not as harsh) lyrics, he produces rap that invites dancing, and he is a more media-oriented figure, with songs featured in TV shows and movies. He has worked as a TV reporter and even co-hosts a show on the GNT channel. In 2021, he gave a series of lectures and interviews at the University of Coimbra. He’s highly active on streaming platforms and social media.

Hip hop

According to Professor Daniela, the research has shown that the periphery, rappers, and music have changed. Songs are now shorter, with fewer samples and more danceable rhythms. The way music is produced has also changed, as has the youth who consume it. Rap, one of the pillars of hip-hop culture, remains in the spotlight, although the other pillars have also transformed. Breakdancing, for example, has become an Olympic sport, not without controversy. Meanwhile, graffiti has transcended street walls, undergoing a process of “artification” and gaining recognition as an art form now displayed in museums and buildings.

Professor Daniela explains that hip-hop has become institutionalized and is now recognized as part of Brazil’s cultural heritage. This process of legitimizing these cultural expressions, according to the researcher, should continue to strengthen, especially as they gain governmental support. There are even projects to bring hip-hop culture into schools, such as the program”Rap-sando a Educação” (Rapping Up Education, in free translation).

Dissemination and Outreach

Professor Daniela has two undergraduate students in Social Sciences studying female rap. She is also a professor in the Sociology Graduate Program at UEL (PPGSOC) and has presented her project at national and international academic events, in addition to giving lectures at UEL and SESC.

She was one of the organizers of the book “Racionais MCs: entre o gatilho e a tempestade” (Perspectiva, 2023, 320 pages) and published an article in Novos Estudos Cebrap (Qualis 1A) alongside Professor Derek Pardue, a scholar of Brazilian Culture at Aarhus University (Denmark). She is also co-organizer of the collection Hip Hop em Perspectiva (name of the publisher), which analyzes the complexity of youth culture in the peripheries. Four books have been published, and the fifth may reach the shelves this semester.

Tradução: Ana Paula Luiz dos Santos Aires. Revisão: Raquel Prete. Supervisão: Fernanda Machado Brener. PFI_ Programa Paraná fala Idiomas.

Matéria originalmente publicada em português na edição nº1427 do Jornal Notícia.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.