Kendrick’s response: a man who “has morals, he has values, he believes in something … He’s a man who can recognize his mistakes … can dig deep down into fear-based ideologies …” I mean, what? Are we really going to let Kendrick Lamar get away with starting a rap feud over a compliment, calling his opponent a pedophilic, Harvey Weinstein-level sex criminal, and finally passing it all off as a movement for love and self-consciousness?

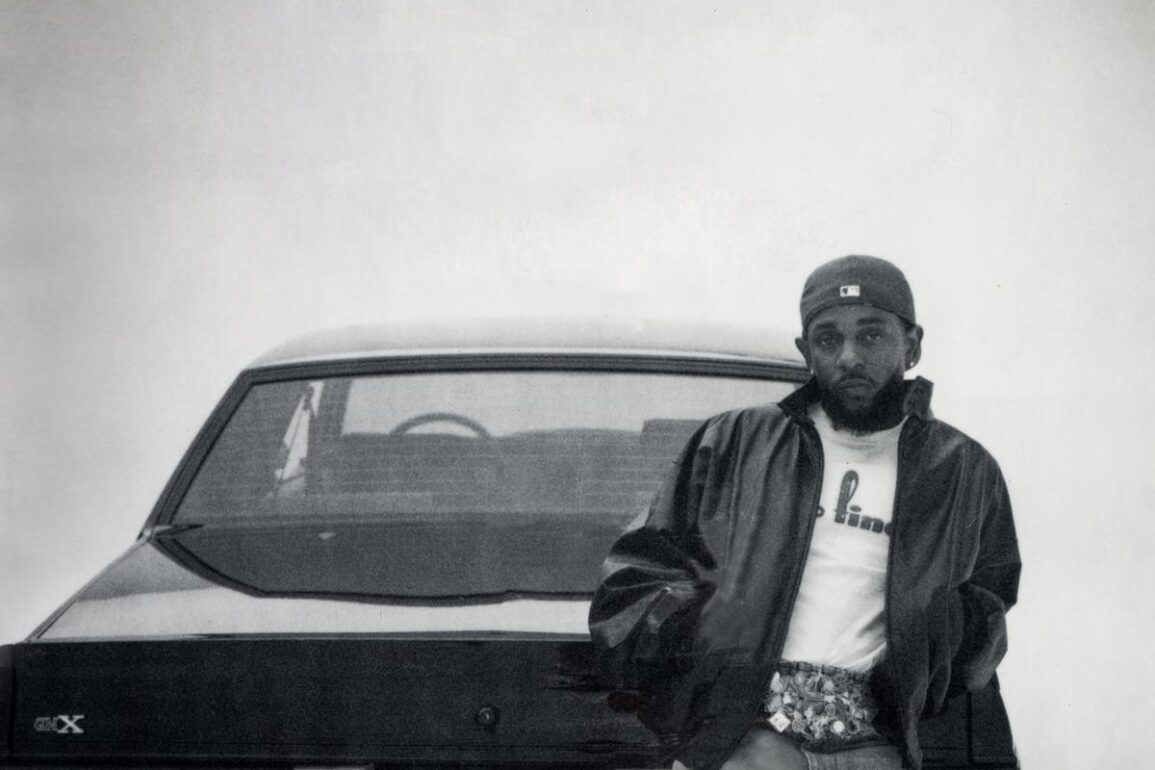

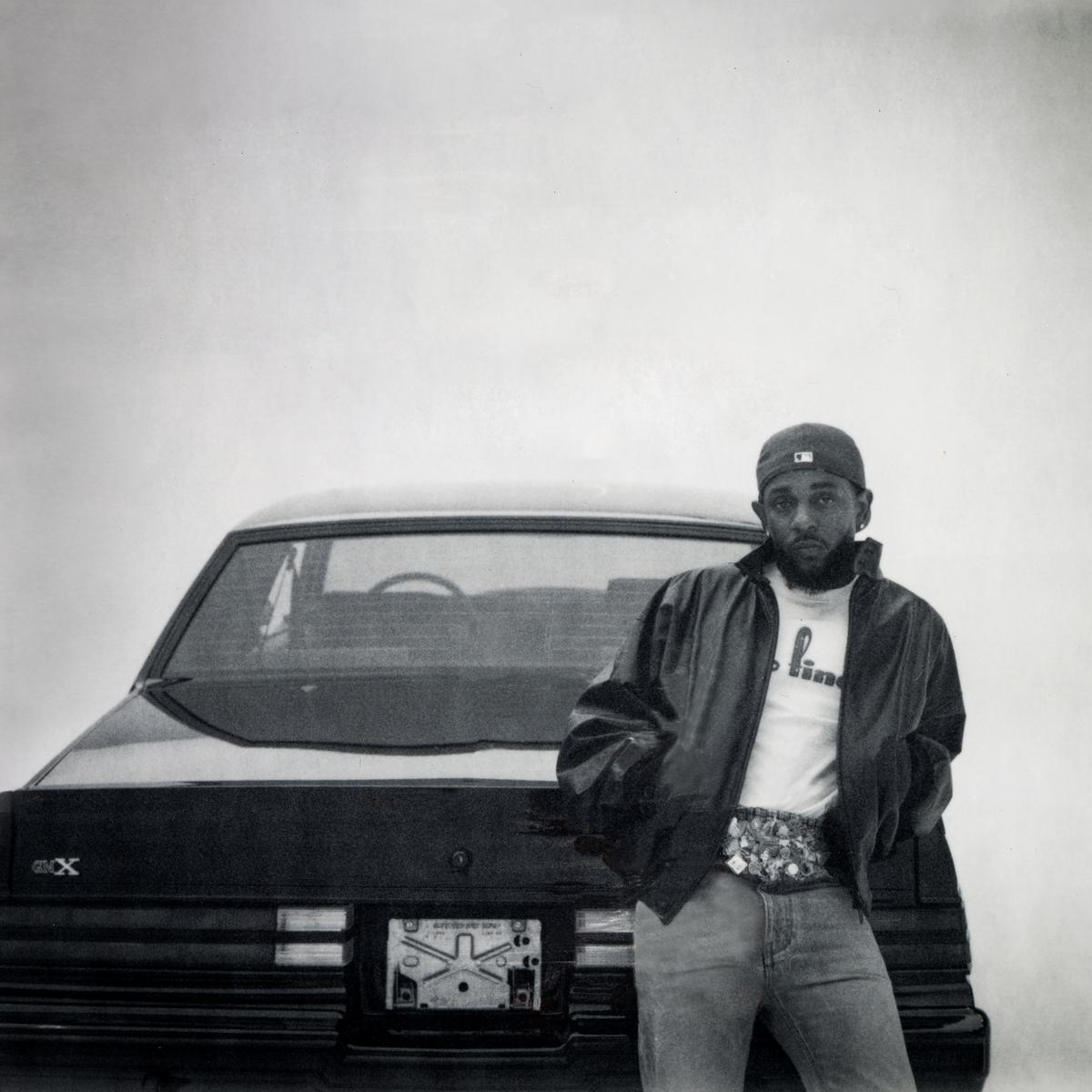

While Kendrick Lamar’s undisputed roundhousing of Drake was ostensibly a victory for Kendrick Lamar, perhaps it truly did symbolize more than that for him. Perhaps the defeat of the poster boy for today’s uninspired rap mainstream symbolized not just a singular win but a victory for Lamar’s perspective on rap itself. There’s a reason he took his victory lap on a stage shared with regional Los Angeles rappers as he united the Pirus and Crips. “Not Like Us” and the songs that preceded it might have been vicious and mean, but they were the means to an end. There is no Big 3 anymore. Lamar’s power is singular. He did this so that he would have the power to reset the rap game, to remake it in his image. And, on GNX, that’s what he does.

GNX is Kendrick Lamar’s vision for the future of hip-hop, and in all honesty, it looks quite a lot like the past. Much like the best rap music of twenty years ago, Lamar reps his hometown, harkens to a hundred years of Black music in more than just sound, and boasts with a flamboyant attitude that justifies itself. It’s fitting that reincarnation plays such an outsized role across GNX, because the album is an attempt at just that: at channeling the soul of a long-dead rap ecosystem and rejuvenating it by trying to bring back its glory moments. It remains to be seen whether or not his attempt to usher in a new genre golden era will succeed, but regardless, GNX is a masterwork in and of itself. This may not be the grand, interwoven concept album that some of his past works are, but it’s just as intricate of a piece: it’s a concise statement of regional pride, braggadocio, and non-conformity.

GNX picks up right where the Drake beef left off: with a loud, menacing threat to the industry. On “wacced out murals”, backed by a heartbeat-like kick drum and dark string hits, he fires shots at just about everybody, even some of his idols: Snoop Dogg, who boosted one of Drake’s disses against Lamar, and Lil Wayne, who claims to have been snubbed by Lamar for the headlining halftime show slot at next year’s Super Bowl. “I’ll kill ‘em all before I let ‘em kill my joy,” he declares. It’s a reminder of two facts: Lamar is at the top of the rap game, and he isn’t happy with how that game looks.

Every move after this track is designed to manipulate hip-hop towards his vision. After Drake’s dethroning, mainstream hip-hop is more malleable than it has been in a long while, and Lamar seems ready to fill the void he created with new friends and nostalgia – the ghosts of his past and the young artists of his future. He sometimes indirectly gloats about his victory, but he largely leaves it ignored; instead, that context allows his boasts to feel that much more justified. Few could get away with an entire song listing the reasons why they’re the greatest rapper of all time, but Lamar pulls it off with perfect poise. While every rapper claims to be the greatest, Kendrick is the first in years to have the evidence, and he acts like it.

All over this album, he uses that immense influence to pay his respects to Los Angeles. He has a whole song dedicated to ripping people who see LA for its rich, gentrified half; elsewhere, he shouts out interstate highways, high schools and regional restaurant chains. This might be Kendrick’s most accessible album in a while, but it’s also his least universal. There are vanishingly few features by Lamar’s contemporaries on this album: other than former labelmate SZA, who appears twice, essentially every featured artist is an up-and-coming SoCal native. This album is for them, and he makes sure to let us know.

The title track is itself a posse cut with a trio of underground LA rappers; Lamar himself takes the backseat, only rapping a hook where he shouts out each rapper explicitly. “Who put the West back in front of shit?” Tell ‘em Kendrick/Peysoh/Hitta/YoungThreat did it! The track itself is comparatively weak, mostly due to an upsettingly wonky instrumental that falls over itself for three whole minutes. Each of the featured artists deserved way better – they rap in top form, as does every feature on this album, even when they only get a few bars.

While Lamar imbues the album with burgeoning regional talent, he also harkens back to old souls. On “reincarnated”, one of the finest storytelling songs of Lamar’s career, he raps over a barely-flipped Tupac beat and waxes poetic about his imagined past lives – a 50s guitarist who manipulated the world to earn respect, a Black woman performer who dies addicted to drugs. By the end of the track, he finds himself arguing with God, promising to use his musical talent for good rather than existing in the infinite cycle of literal ego death. It’s a deeply powerful moment, and one where he situates himself in the history of Black music as a whole, both criticizing its corruptions and finding its beauties.

Lamar does a lot of calling back on this album: he trios with SZA and a sample of Luther Vandross and references Anita Baker on the album’s first and last tracks. On his sixth installment of The Heart series, he dedicates verses to his friends as he came up – Jay Rock, Dave Free, Punch – and paints a series of beautifully detailed memories about his early career. As much as this album looks forward to the future of hip-hop, it dedicates a significant amount of time to hindsight, both near and far.

And yet, the album isn’t dated – it’s very much inspired by the sparse synth melodies and drums of modern trap music. The album was produced in large part by (surprise!) Jack Antonoff, who has clearly taken a break from producing sleepy synthpop for Taylor Swift to suddenly become very, very good at West Coast hip-hop. His work implementing conspicuous flipped samples with unique electronic instrumentation and subtle sound effects has made this album feel lush and expansive, existing in conversation with the past while sounding consistently novel. That distinguishes this album from a pure journey to nostalgia-land: it’s inspired by those who inspired Lamar, and by those who inspired his heroes, but it’s undoubtedly a mid-2020s Kendrick Lamar album. Mainstream hip-hop hasn’t sounded this fresh in a long time, and it’s clear that Kendrick Lamar wants that back.

As he recently admitted on in an Instagram-only drop, Kendrick Lamar has been itching for the destruction of what he sees as a malformed, corrupted hip-hop culture – a culture perhaps best represented by Drake, may he rest in peace. In the absence of his main rival, GNX sees Lamar stepping in to fill the power vacuum that he himself created. Every moment this year led up to this: from the first shots fired to the post-beef limbo of his genre, Lamar was preparing to flex his muscle so that he could execute a coup over the rap industry. With this album, that process is complete. And while some songs on this album get drowned out by the grandiosity of its goals, the project – and the man behind it – are as strong as ever. GNX is the blueprint for a new rap zeitgeist, and all we can do is hope that everyone gets the cue.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.