As Tone Madison‘s 10th anniversary approaches, we look back at some highlights from the past decade.

Tone Madison turns 10 years old this year. To mark a decade of our fiercely independent, reader-supported coverage of culture and politics in Madison, we’re revisiting some highlights from our archives. Got a favorite Tone Madison story you think we should include? Let us know by sending an email to editor@tonemadison.com.

“The situation on State Street is an interesting microcosm of today’s movements with non-Black people, in poorly formulated attempts to be allies and spread whatever their personal notions of ‘positivity’ may entail, speaking over the Black voices envisioning what a better future could look like and how it can be built. The murals have the potential to start a conversation beyond the artwork itself, one that addresses what it means to listen without taking up space.”

—Sannidhi Shukla

Editor’s note: Art is politically contested. It’s economically hairy. Public art especially is so often a debate about who gets to access and shape different public spaces, and about which messages belong where. God knows we can’t leave it to tourism programs and property owners to deck out the city’s outdoor walls with (even more of those goddamn) flamingos and soothing platitudes. We need to keep growing our actual public-art programs—publicly funded efforts that elevate a variety of local artists without watering down their expression—and stop clutching our pearls so much about illegal street art.

Sannidhi Shukla captured an explosive moment in that debate with her June 2020 report on a City of Madison-sanctioned mural project along State Street. Amid the nationwide uprising following the murder of George Floyd, broken and boarded-up shop windows downtown became fertile ground for the most diverse and overtly political public art project that has confronted Madisonians in recent memory. Artists, businesses, the public, and City officials—in some cases the same officials who backed violent police crackdowns on protests and put a disingenuous spotlight on property damage—had to tussle about all this out in the open. Those conflicts kept playing out as people memorialized and made plans to preserve the resulting art.

As Shukla reported, the biggest disruption to the City art project came from “vigilante painters” helping themselves to the vast plywood canvas to create works that “were toothless by comparison, filled with images of flowers and calls for unity.” But most of the artists in the project weren’t having it. Beautiful, often blistering works carried the day, tackling the racial politics of the moment head-on. That summer, the odds that you would’ve encountered people of color in downtown Madison, and that you would’ve heard what they had to say in powerful, unvarnished terms, increased about a thousandfold.

Tone Madison Music Editor Steven Spoerl is also a great photographer, and spent a lot of time that summer walking around downtown, documenting art that ranged from sanctioned murals to spontaneous graffiti. A few of his photos accompany Shukla’s deft weave of cultural critique and on-the-ground reportage.—Scott Gordon, publisher

Amid ongoing protests, artists in a city-sanctioned mural program try to ask some probing questions.

Originally published June 8, 2020.

On May 30, Madison activists began a major series of protests in solidarity with George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter movement at large. By that evening, police marched their riot lines up and down State Street, equipped with tear gas and willing to use it liberally against unarmed civilians. The street was transformed almost overnight, changing from one of Madison’s most popular destinations into a street whose every surface became marked by the moment. Face-burning gas lingered in the air. Broken glass, upturned planters, and the debris of militarized policing littered the street.

In the wake of the damage, State Street has been transformed entirely once again. Its storefronts, many of them shattered in the intensity of the protests of the past 10 days, have been covered with thick boards of plywood. The graffiti tags protestors have left as a more permanent reminder of the fight against police brutality are still scattered up and down the street. In between them, Madison artists have painted a series of murals over the past week that promote messages of community and empathy.

City of Madison Madison Arts Program Administrator Karin Wolf commissioned the murals on Sunday morning at the request of Mayor Satya Rhodes-Conway and Common Council President Sheri Carter, though some of the murals currently displayed were sanctioned directly by businesses, and yet others were the completely unsanctioned work of volunteer clean-up crews. Wolf says she set out to “amplify the voices of people who have been directly impacted by racial injustice,” and initially selected a list of 12 artists to begin work on the project, with plans to bring on more artists through an open call over the course of the week. The project guidelines ask only that artists do not incorporate commercial messaging into their murals and “keep it family-friendly” by not depicting nudity.

The project gives the artists involved a platform that’s at once powerful and fraught with political conflict. Rhodes-Conway, Carter, and other local officials have drawn criticism for supporting violent police tactics and now-expired curfews. They’ve drawn distinctions between “peaceful” protestors and those who engage in rioting or looting, distinctions that organizations leading the protests have rejected as divisive and simplistic. And in Madison, like anywhere else, there’s been a tendency for people to treat property damage as an evil equal to the injustices that fuel the protests.

As the week progressed, painters began to flock to State Street in droves—including groups of white painters who weren’t part of any real coordinated effort beyond the outpouring of support and funds for damaged businesses, but sought to leave their own mark on many of the yet untouched storefronts. The artists participating in the city program painted celebrations of Black lives and calls to action. The murals these vigilante painters left behind—often on spaces that Wolf and business owners had agreed to set aside for artists of color—were toothless by comparison, filled with images of flowers and calls for unity. Given their context, these murals feel more akin to a declaration that “all lives matter” and an attempt to quite literally paint over the pain, rage, and hopes of those protesting than a thoughtful attempt to respond to this crucial historic moment through art.

“What it did was just kind of illustrate Madison. They took over spaces that were meant for other people,” says Wolf of these non-commissioned painters. “It’s an unnecessary complication in a time we should be focusing on making cultural change and now we have to navigate white privilege. It’s endless.”

The situation on State Street is an interesting microcosm of today’s movements with non-Black people, in poorly formulated attempts to be allies and spread whatever their personal notions of “positivity” may entail, speaking over the Black voices envisioning what a better future could look like and how it can be built. The murals have the potential to start a conversation beyond the artwork itself, one that addresses what it means to listen without taking up space.

Notably, the Madison Police Department has reported arresting people accused of painting graffiti downtown in the past week, during the ongoing protests. That this happened as the city has commissioned artists to paint boards in the same area further underscores the strange and often contradictory relationship between street art and officially sanctioned “public” art.

The work artists actually created for the city-funded program still stands proudly on State Street. Brooklyn Doby, a recent graduate of Edgewood College’s art therapy program, painted two murals on State Street. One of these murals, a collaboration with Ciara Nash and Synovia Knox in front of the Campus Ink tattoo shop at 514 State St., shows three silhouettes of Black protestors participating in their own ways—one wears a shirt that reads “#SayHisName #SayHerName #SayTheirNames,” one raises a fist, and one holds a camera to document the protest—alongside the quote “Once there’s justice we’ll rebuild something beautiful” below a painting of the Earth.

“That’s our way of saying we are a part of the protests even if it looks different,” says Doby. “We just want to be heard, we want to be seen, we want to create change, we’re looking for hope.”

Nash says the artists chose to make the mural’s background orange for the color’s ability to “boost people up.”

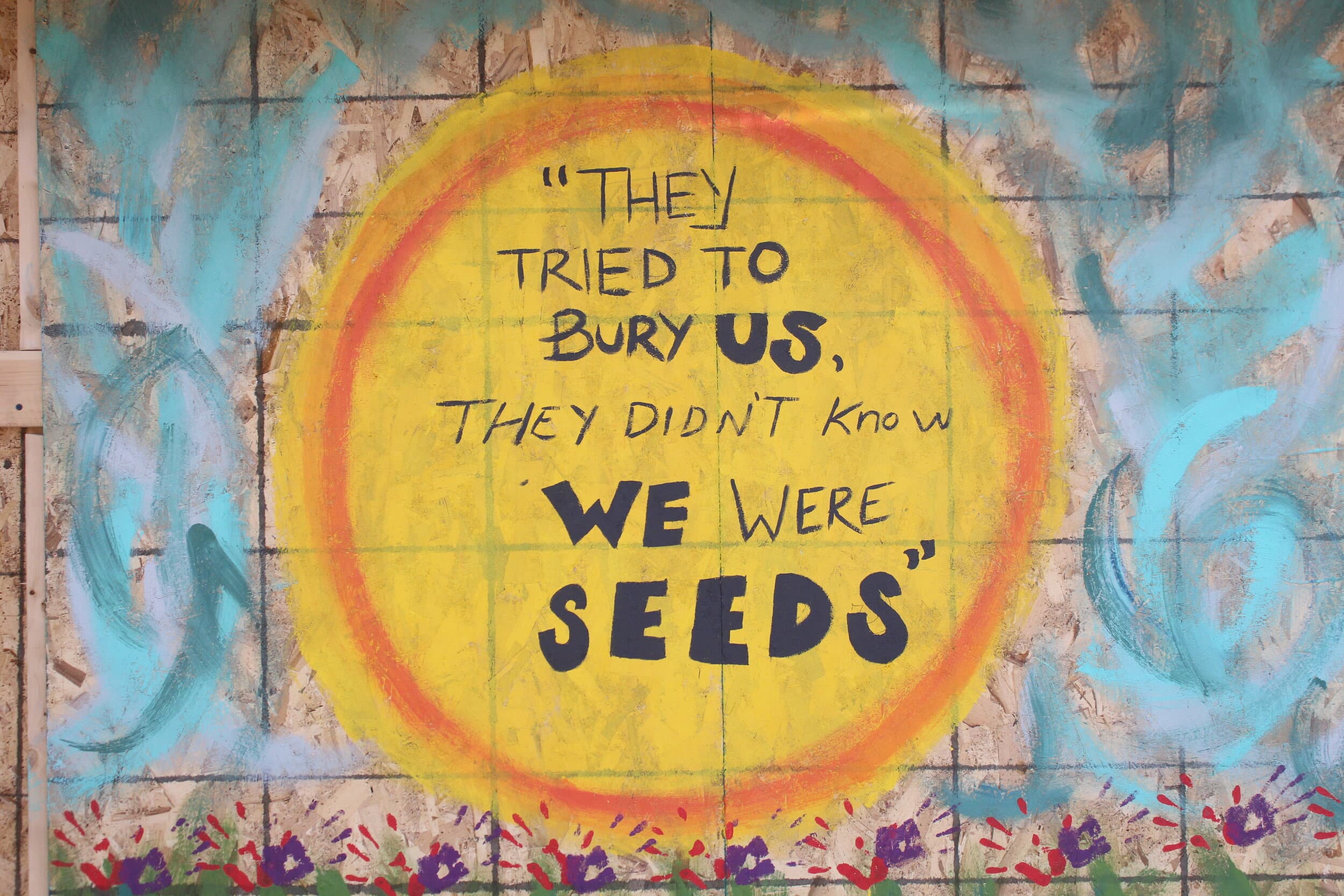

Doby’s second mural, painted with Nash in front of Short Stack Eatery at 301 W. Johnson St., features flowers set against a blue sky with the phrase, “They tried to bury us but they didn’t know we were seeds.”

Doby hopes that her murals will inspire passers-by to look inwards and think more deeply about their involvement in the moment. “Whether it’s negative or positive talk it makes you stop and really reflect on, what are you doing during these times to advocate for someone else or to be part of a cause? Or are you not doing enough?” she says.

Daniella Echeverría, another of the artists Wolf commissioned, created the mural on the boards covering the broken gift-shop windows of the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, 227 State St. The painting features the phrase “Silence is violence” between two skulls crowned in green and orange leaves. Echeverría says her mural takes its cues from the way that fires, often thought of as a destructive force, can give birth to new plants and new life. The piece also points out the capacity of silence and complicity to breed violence and destruction.

“People need to sit with the discomfort of these boarded-up windows and how their silence helps perpetuate white supremacy,” says Echeverría, who found herself having mixed emotions about the project. “It was really frustrating people walking by and saying, ‘Oh, thanks for turning this into something really positive!’” she says. “It’s hard to feel like what you’re doing isn’t just painting over this problem and not actually involving all communities.”

Ultimately the murals on State Street are just only one small step towards drawing attention to the white privilege and anti-Blackness that ooze through Madison and has revealed itself even in the midst of this project itself. Both the businesses on State Street and the city as a whole must look within to become more welcoming and equitable for Madison’s Black citizens.

“My hope would be for the businesses on State Street to start incorporating more Black art […] or just being more accepting of Black people. Letting them know that they are a friendly face, that they are welcome in their establishment, not discriminating against people when they walk in their stores,” says Doby.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.