By Erica C. Barnett

Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell, King County Prosecutor Leesa Manion, and City Attorney Ann Davison announced charges against 16 people for graffiti in and around Seattle. According to Manion, it cost more than $100,000 to clean up graffiti by the 16 charged individuals.

One tagger whose name came up frequently in the charging papers, Joseph Johnson—best known by his tag GRIDE—died earlier this year.

The investigation took more than a year, according to Manion, who declined to estimate the cost of investigating, arresting, jailing, prosecuting, and potentially imprisoning the 16 charged individuals.

“I can tell you that I’m sure that it cost way less than $6 million for us to bring this case, but we know that in the city of Seattle alone [it costs] $6 million to remove graffiti, and that does not consider the expenses that private business owners have to spend,” Manion said.

According to Harrell’s office, the $6 million includes all annual expenditures for an interdepartmental team that includes the Office of Arts and Culture, Seattle Center, Finance and Administrative Services, Seattle City Light, the Seattle Department of Transportation, Seattle Public Libraries, Seattle Parks and Recreation, and Seattle Public Utilities. It’s unclear how much of that is direct graffiti abatement. Harrell’s “One Seattle Graffiti Initiative” includes 11 full-time employees in the parks department, including executive-level staff and nine “graffiti rangers.”

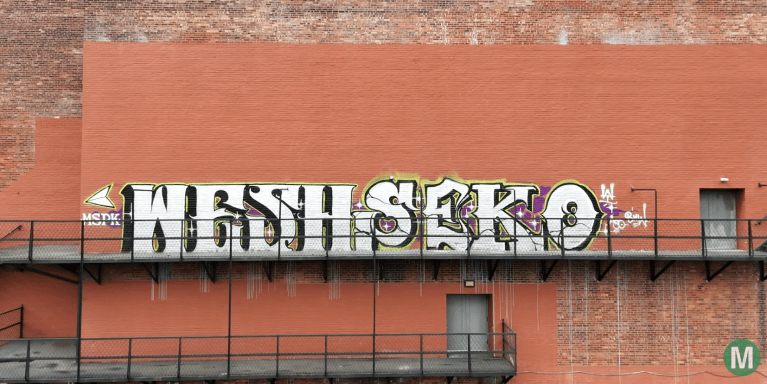

Charging documents show that much of the evidence collected over the past year stems from a publicly available documentary called “Make It Rain,” posted on Youtube in June. Investigators watched the video (which is dedicated to Johnson’s memory) and compared it to publicly available images on Instagram and mug shots of the featured taggers, most of whom had arrest records already. In addition to the videos, some of the charges stem from arrests made as far back as 2021, as well as messages and videos on phones seized by police.

” data-medium-file=”https://i0.wp.com/publicola.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/64812CE5-0894-4515-9C14-790DC52297BC.jpg?fit=300%2C230&ssl=1″ data-large-file=”https://i0.wp.com/publicola.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/64812CE5-0894-4515-9C14-790DC52297BC.jpg?fit=845%2C647&ssl=1″ class=”size-medium_large wp-image-42969″ src=”https://i0.wp.com/publicola.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/64812CE5-0894-4515-9C14-790DC52297BC.jpg?resize=768%2C588&ssl=1″ alt width=”768″ height=”588″ srcset=”https://i0.wp.com/publicola.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/64812CE5-0894-4515-9C14-790DC52297BC.jpg?resize=768%2C588&ssl=1 768w, https://i0.wp.com/publicola.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/64812CE5-0894-4515-9C14-790DC52297BC.jpg?resize=300%2C230&ssl=1 300w, https://i0.wp.com/publicola.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/64812CE5-0894-4515-9C14-790DC52297BC.jpg?resize=1024%2C784&ssl=1 1024w, https://i0.wp.com/publicola.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/64812CE5-0894-4515-9C14-790DC52297BC.jpg?resize=1536%2C1176&ssl=1 1536w, https://i0.wp.com/publicola.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/64812CE5-0894-4515-9C14-790DC52297BC.jpg?resize=150%2C115&ssl=1 150w, https://i0.wp.com/publicola.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/64812CE5-0894-4515-9C14-790DC52297BC.jpg?w=1629&ssl=1 1629w” sizes=”(max-width: 768px) 100vw, 768px”>

Tom Graff, president of the Ewing and Clark real estate company and the head of the group Belltown United, told reporters that graffiti has made his neighborhood, and the condo tower where he lives, feel unclean and unsafe.

“How would you feel if your garage door was spray-painted [by] a tagger?” Graff said. “That happened on my tower. … How would you feel to drop off your child in a school that has its front door covered with a graffiti image? You would not take your child there, and we expect the people who live and work downtown to put up with it, and it is unacceptable, and it has to stop.”

Manion is charging all 16 suspects with second-degree malicious mischief, a Class C felony that carries a prison sentence of up to five years and a fine of $10,000. She said her primary goal is to make the taggers pay restitution to all the property owners they have harmed.

“We are seeking accountability for what amounts to felony- level behavior, so it is appropriate to file felony charges,” Manion said. “It is not the jail time and the incarceration that we think will make a difference. It is getting folks to pay for the damage that they have caused.”

” data-medium-file=”https://i0.wp.com/publicola.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/68E03545-926D-4B08-8DBE-48B52D305558.jpg?fit=300%2C169&ssl=1″ data-large-file=”https://i0.wp.com/publicola.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/68E03545-926D-4B08-8DBE-48B52D305558.jpg?fit=845%2C474&ssl=1″ class=”size-medium_large wp-image-42974″ src=”https://i0.wp.com/publicola.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/68E03545-926D-4B08-8DBE-48B52D305558.jpg?resize=768%2C431&ssl=1″ alt width=”768″ height=”431″ srcset=”https://i0.wp.com/publicola.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/68E03545-926D-4B08-8DBE-48B52D305558.jpg?resize=768%2C431&ssl=1 768w, https://i0.wp.com/publicola.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/68E03545-926D-4B08-8DBE-48B52D305558.jpg?resize=300%2C169&ssl=1 300w, https://i0.wp.com/publicola.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/68E03545-926D-4B08-8DBE-48B52D305558.jpg?resize=1024%2C575&ssl=1 1024w, https://i0.wp.com/publicola.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/68E03545-926D-4B08-8DBE-48B52D305558.jpg?resize=1536%2C863&ssl=1 1536w, https://i0.wp.com/publicola.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/68E03545-926D-4B08-8DBE-48B52D305558.jpg?resize=150%2C84&ssl=1 150w, https://i0.wp.com/publicola.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/68E03545-926D-4B08-8DBE-48B52D305558.jpg?w=1620&ssl=1 1620w” sizes=”auto, (max-width: 768px) 100vw, 768px”>

During the press event, officials repeatedly offered their own definitions of what is, and isn’t, “art.”

Manion insisted that there is a “clear distinction between art” and “illegal vandalism.” Art, she said, includes government-sanctioned wall murals displayed in “appropriate outlets for talented artists and appropriate places for them to display public art,” like the county-funded murals visible to light rail riders in SoDo.

Art, Graff added, is an officially sanctioned mural that “the landlord approved,” like 12 city-funded murals in Belltown that received city funding. “The artist was assigned this wall,” Graff said. “It is not done randomly, and it doesn’t damage the property.”

Art, Harrell said, might include a freeway wall that, with approval from the state Department of Transportation, might be used as “a canvas that can be painted by an artist, some of our beautiful sunsets, sunrises, or some of our Native American art.”

What isn’t art? Manion gave a few examples. “Dangling above freeway lanes to tag a traffic sign is not art,” she said. “Destroying a mural in Kent with a tag is not art. … Tagging Metro buses and Sound Transit cars is not art.” The charging documents say graffiti tags exist for two purposes, and art is not one of them: They can either be “ideological”—a category that includes hate speech—or designed for “fame and glory.”

The history of government officials deciding what is and what is not art has, shall we say, a long and ignominious history.

But even assuming officials’ definition of “art” (to summarize: pre-approved murals; sunsets and/or sunrises; “Native American art” generally) is partial and not didactic, Seattle has an obsession with graffiti, cleanliness, and the need for “order” that warps city spending and serves as cover for cracking down on people whose ideologies (or existence, in the case of encampment “cleans”) conflict with official government priorities.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.