An exhibition of his impressive collection compels our art critic to ask if we should start taking the world famous street artist’s project more seriously.

The artist known as KAWS in London, 2022.

(Tolga Akmen / AFP via Getty Images)

I’ve never been interested in the art of KAWS. Like Damien Hirst, Jeff Koons, Takeshi Murakami, and very few others, KAWS (born Brian Donnelly) has succeeded in leaping across the boundary between Pop art and a broader realm of just plain popular art. Like them, his oeuvre—as a graffiti writer turned painter/sculptor/designer—ranges from collectible merch that average folks can afford to unique works on a monumental scale. But I’ve never bought it. His work, reliant on a mini-universe of figurines and characters, might be appealing in small doses but lacks substance; it might be almost universally comprehensible, but so is Hello Kitty or the Energizer Bunny. In fact, I didn’t even bother to make the 20-minute walk from my apartment to the Brooklyn Museum when KAWS had his big survey exhibition there in early 2021.

Now I wish I could see that exhibition. It still probably wouldn’t make a convert of me, but I might be able to see more in it than I would have back in 2021. What made the difference is that now I’ve seen the remarkable exhibition “The Way I See It: Selections from the KAWS Collection” at the Drawing Center in New York. Today, at least, I’d be able to look at his retrospective with the certainty that KAWS is an artist and not, as I might have said before, an art director masquerading as one. I dismiss out of hand the assertion of the Drawing Center’s director, Laura Hoptman, that KAWS has “to some extent bested the hegemonic lens of the institutional art world in part because of the international popularity of everything he makes,” which would replace an aesthetic judgment with a quantitative socioeconomic measurement, a mere accounting (whether of “likes” or of dollar signs).

The exhibition itself, which primarily features artists who have neither achieved nor sought the kind of worldwide success that KAWS enjoys, refutes that. But I may well have been too hasty in my judgment—and as KAWS himself says in an interview in the Drawing Center’s exhibition catalog, “There are a thousand ways to exist as an artist and many different trajectories.” KAWS can clearly appreciate many of them. And his interlocutor, Valérie Rousseau, a curator at the American Folk Art Museum, is categorical: “There is not a real unity across your collection,” she says. “I see such contrasts, for instance, between the irreverence of Peter Saul and the internalized scientific concepts in abstract form of Hilma af Klint and the incredible travelogue of Adolf Wölffli”—Saul, a highly erudite pictorial satirist and Pop expressionist; af Klint, the Swedish painter who threw over her 19th-century academic training to explore theosophical mysteries through colorful diagrammatic symbols intended for a “temple” that never came to be; and Wölffli, af Klint’s Swiss contemporary, who began drawing, painting, and writing after he was committed to the psychiatric hospital where he spent the rest of his life.

What is so impressive about the collection, however (or at least the small part of it that is being exhibited, about a 10th of the 4,000 pieces that KAWS owns), and what makes one want to say that it could only have been assembled by an artist, is that it gives such a vivid sense of how the “thousand ways to exist as an artist” are, at some deeper level, at one. There can be a mutual recognition among artists of very different sorts, and very different kinds of artwork can be recognized as sharing an essential similarity. But how can that similarity across categories (both social and aesthetic) be articulated? Why does it make sense to see a drawing by a modern master like Willem de Kooning (portraying a “clamdigger” whose wildly distorted body is formed of countless little spasmodic charcoal marks), together with ones by a contemporary painter such as Nicole Eisenman (a quasi-Surrealist beach scene in which a nude woman lounges on her blanket, revealing that her derriere has eyes), an “outsider” like Henry Darger (three complex tableaux from his famously incomprehensible narrative cycle about the Vivian Girls “in the realms of the unreal”), graffiti writers like DONDI (Donald Joseph White, represented here by whole sketchbooks as well as individual sheets), and comics artists such as Robert Crumb (also with sketchbooks as well as drawings)? Or rather, why do all of them make more sense together than they would separately? It’s because together they tell us something about the constantly transforming yet always urgent impulse to make pictorial art—an impulse that no one mode of expression can exhaustively embody and convey.

That artists are also collectors—and in this, KAWS differs from many other artists I know only in the sheer quantity of things he has had the means to amass—makes sense when one considers that, in some deep part of the mind, picturing something and possessing it are hard to disentangle. Maybe that was already the case in the caves where early humans depicted the animals they presumably wanted to bring back in their hunts, and perhaps that unconscious thought was still in operation somewhere at the root of the Duchampian readymade, in which acquiring and making were equated in a new way suitable to the burgeoning consumer culture of the 20th century.

Artists who have undergone conventional formal training, or who participate in the established art world—one that’s populated by people who are aware of the accepted terms of discussion and the standard narratives of art’s history—make work whose basic parameters are readily understood by viewers who share a similar background. If I see a painting whose visual vocabulary seems based on Cubism, for instance, I can assume that the artist is familiar with the Cubist works of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque; that they are self-consciously quoting this style and expect viewers to realize that this is so; and therefore that the reference is part of the meaning as well as of the form of the painting. As Renato Poggioli long ago observed, “The reaction of modernism to tradition is one more bond, sui generis, to that very tradition. Avant-garde deformation, for all that the artists who practice it define it as antitraditional and anticonventional, becomes a tradition and a stylistic convention.” But if I notice something like a Cubist visual vocabulary in the work of an artist who might be unfamiliar with Cubism as a historical art movement, an artist who might have arrived at this way of working independent of commonly held art-historical information, then I should be much less certain about what I am looking at—of what the work is and why the artist made it. This state of uncertainty turns out to be a favorable condition for aesthetic appreciation.

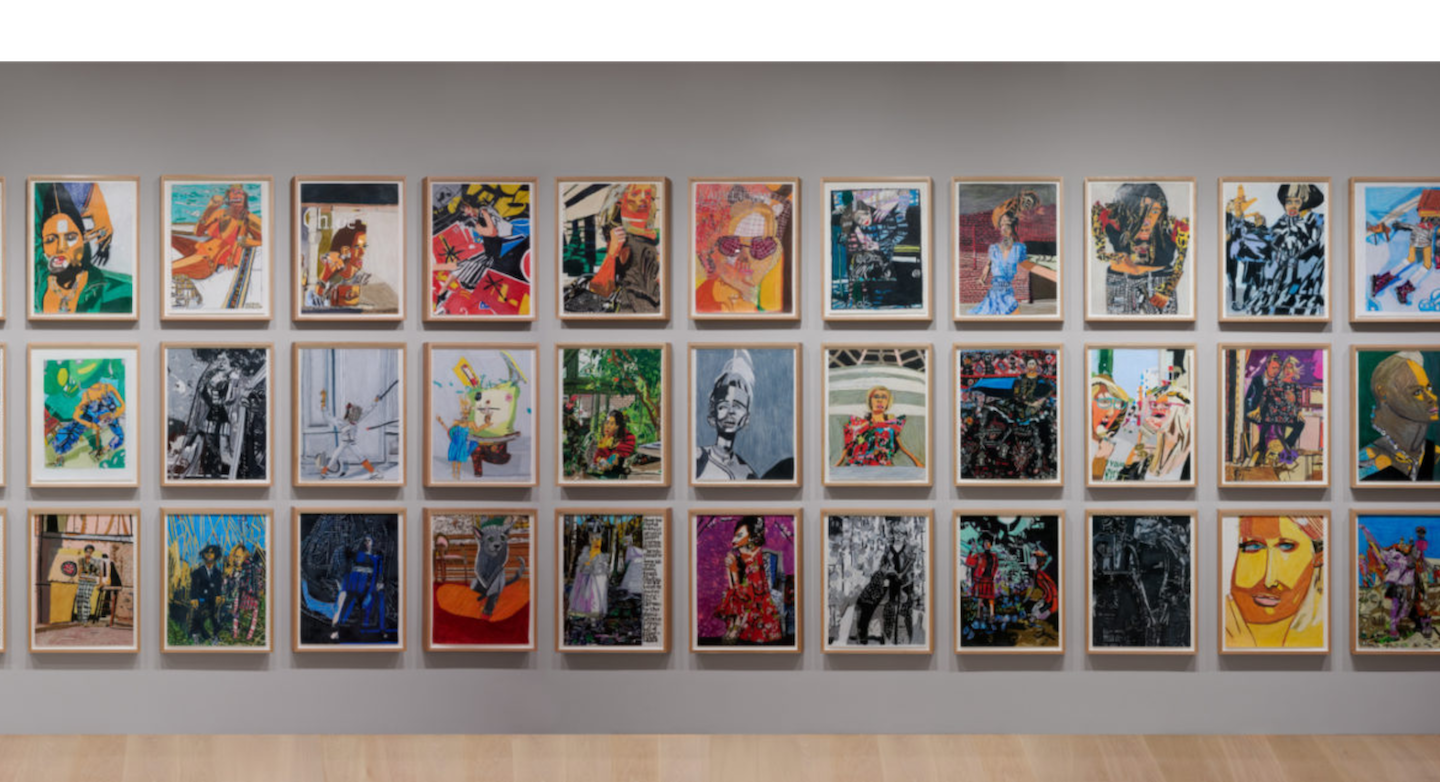

Here at the Drawing Center, I felt that kind of uncertainty keenly at times, and never more so than in front of a wall of 48 color-pencil and graphite drawings by Helen Rae, amounting to an extraordinary one-person show within the group show. The structural deformation of her figures, and the fragmented, reconstructed, and flattened space in which they occur, really do recall aspects of Cubism, while the choice of imagery—much of it clearly derived from fashion magazines—might make one think of a contemporary artist such as Karen Kilimnik. But my guess is that Rae (who died in 2021, at the age of 83) had no idea about the innovations of Picasso and Braque; nor did she follow the contemporary art scene on which Kilimnik rose to quick notoriety around 1990—about the same time that Rae, who was deaf and described as “completely nonverbal,” began making art at a center for adults with developmental disabilities in her hometown of Claremont, California.

Rae exemplifies a type of artist who is less uncommon than we might think: one whose intentions remained unarticulated (except in the work itself), who work without the ballast of theory or tradition or an imagined audience. What did Rae want her art to say? What did she want it to do? Is it an expressive act, or does it embody a form of making that is fundamentally self-enclosed and incommunicative? To think that what it says to me, what it does in my eye, has much to do with anything she had in mind would be unsupported speculation.

The most astute, and certainly one of the most passionate, responses to Rae’s work was that of the Los Angeles critic David Pagel, writing when her work was shown for the second time, in 2016. “Rather than shoring up a viewer’s sense of self, her radically fractured compositions invite us to dip our toes into a world in which lampposts, potted plants and handbags are as fascinating as any human being, depicted or living,” he wrote. “The electrifying energy that pulses through her pictures gives form to a cosmos that is not anthropocentric.” Certainly, Pagel’s perception in these works of a pulsating energy—an intense and jagged rhythm that is somehow stronger, more vivid, than any particular depicted thing—is one I can’t help but share. But do we need to make the leap with him to the conclusion that these pictures—almost all of them centered on human figures, however fractured and stylized—embody a non-anthropocentric vision, something perhaps comparable to, but even more extreme than, that “dehumanization” that José Ortega y Gasset saw as typical of the early 20th-century avant-gardes? I’m not necessarily convinced. But I am sympathetic to his view that Rae’s work produces a profound sense of unfamiliarity in what would otherwise be quite familiar kinds of imagery, and that this can make the viewer “feel like an alien—out of place in a world that shares significant features with everyday reality but is charged with a kind of sizzling energy that is both exhausting and intoxicating.” There’s an irony in that: Artists like Rae are often described as outsiders, but experience suggests that we apply this label defensively. It’s not that an artist like Rae is an outsider but rather that we viewers become outsiders in the face of an art that we can’t help responding to, but without ever knowing if the response has any necessary connection to it.

There is something incomprehensible about an art like Rae’s—incomprehensible, and yet it compels recognition. What I don’t understand about this artist’s relationship with the commercial culture whose products she is at once emulating and demolishing speaks, all the more powerfully perhaps for doing so involuntarily, to my conflicted relation to it and to the parts of myself that I feel being formed and deformed by it. This quandary about understanding touches on one of the deep, insoluble ambiguities about art: Is it primarily an effort at communication, or is its essence somehow more internal, even solipsistic? When it comes to those who’ve been called “outsider artists” in the classic sense—often people who have been left profoundly isolated by psychiatric or other conditions, as in the cases of Wölffli or others whose work is included in KAWS’s collection, such as Susan Te Kahurangi King (who stopped speaking at the age of 8) or Martín Ramírez (who spent half his life institutionalized as a schizophrenic with a tendency to catatonia)—I felt for a long time that their art embodied an attempt at communication by individuals suffering an unwilling isolation. But the more I see their work, and the more I think about it, the more convinced I become that they found worlds within worlds within themselves and that they were moved to incarnate those inner worlds in the form of artworks simply in order to hold on to them, to develop and cultivate them for their own sake. Some unimaginable necessity has forced them to construct a culture of one. We, the viewer, are irrelevant to this aim.

What, it might be asked, does this utterly self-contained quality I attribute to so-called outsider artists have to do with other kinds of art, which as history shows us have always been social phenomena, the product of guilds, schools, coteries, and movements, no matter how narrow or broad, powerful or marginal, unified or conflicted? Most often, artistic achievement is forged through a process that’s best characterized by a phrase I picked up from Albert Murray (though he got it from Ralph Ellison): “antagonistic cooperation.” In the Drawing Center’s exhibition catalog, Nicole Rudick quotes Henry James’s adage on this broad historical process: “Art lives upon discussion, upon experiment, upon curiosity, upon variety of attempt, upon the exchange of views and the comparison of standpoints.” The point of all these exchanges and comparisons, though, is not a balancing or moderation of differences, but rather the sharpening and even the stylization of individual identity—of which no better example can be found than James’s own intensely constructed late prose style.

Here at the Drawing Center, it is particularly revealing to see the drawings of the New York graffiti artists of the 1970s and ’80s, whose sketchbooks evidently hold a particular fascination for KAWS. It was with them, in fact, that his collecting began: “When I was younger and doing graffiti,” he recalls, “I would trade ‘black books’ with other artists. They would draw in your book, and you would draw in their books.” One senses that this milieu was a tight-knit community that might have been intensely competitive but was united by its adherents’ self-chosen distance from the mainstream art world and even from legality. The graffiti writers’ main subject matter was their own “tags” or adopted monikers: an assertion of identity, for sure, but one that always tended to break down into pure form—which, perhaps unsurprisingly, is when they begin to show their underlying affinities, whether conscious or otherwise, with more institutionally accepted forms of modern art.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Some of the designs by CRASH (John Matos), for instance, are bluntly legible, but more often they are like intricate puzzles in which the intertwined forms can only be made out with a degree of effort not unlike that required to disentangle the fragmented components of a Cubist still life. A 1988 drawing by PHASE 2 (Michael Lawrence Marrow) is a completely illegible mound of what might be letter forms that have been bent and twisted beyond all recognition; it reminded me of the relentlessly scribbled little shapes that fill the surfaces of certain works by Jean Dubuffet. A tightly linear, geometrical marker drawing from 1981 by Eric Haze—who now exhibits in galleries rather than underground—seems to emulate the Suprematism of Kazimir Malevich. In each case, the association with modernist painting might reflect nothing more than my own subjective impression, but what these works confirm is that the artists’ efforts to push their work into ever more extreme stylistic territory introduce a form of abstraction that decomposes the very identifiability, the trademark quality, that the “tag” or signature seems to assert. And if I can’t help translating aspects of their work into terms I learned from forms of art that are more familiar to me, it’s not because one validates the other; it simply shows that similar impulses arise in very different art worlds.

Those connections across the boundary between “high art” and “street art,” however arbitrary they might be, also confirm what I found to be the main takeaway from this show: that artists of different backgrounds, with distinct kinds of training or even none at all, are responding to similar needs and are therefore capable of inventing similar methods of fulfilling those needs. And drawing is where those commonalities are most likely to reveal themselves, thanks to the immediacy and availability of its materials. KAWS himself points to the similarity between the visual idioms of a self-taught artist such as King and a highly sophisticated one like Peter Saul, despite the fact that, as he says, “they are creating in two completely separate worlds,” while also noting that a Peter Saul from 1960 works very differently from one made in the 1980s. An artist can be more different from himself than he is from another artist, while the separation between one kind of artist and another may be more superficial than we think. KAWS describes the unity of this amazing array of art as, simply, “People making marks.”

It sounds simple, even basic, and it can be—until you start wondering why human beings, even in the absence of any evident need or utility, are possessed by this unquenchable need to make marks, traces of oneself and of what is utterly outside oneself—and by so doing, to magically make something visible that wasn’t there before. There is something fundamental about the urge to make art, to make a mark, that remains as unarticulated as it is inescapable. Right now you can feel closer to grasping what that ineffable something is at the Drawing Center than anywhere else. I’m only left wondering why, if KAWS understands art as deeply as this show suggests, his own work never seems to plumb those depths.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.