The decorative arts of the 19th century, and specifically Pennsylvania Dutch utilitarian stoneware, are rarely associated with hip-hop culture. Rarely, but, as visitors to “Timothy Curtis: The Painters’ Hands” at the Current in Stowe will learn, not never.

Curtis introduced his exhibition, which is on view through April 12, with a brief artist talk last Thursday. He is not your typical leather-elbow-patches-and-bow-tie art historian. The self-taught painter, who now lives in New York City but whose work is strongly rooted in Philadelphia, began his studies while incarcerated.

Before then, growing up in the 1990s in North Philly’s Kensington neighborhood, he was fascinated by graffiti. “When I was a young kid, around the age of 9, it felt like everybody was kind of born into graffiti,” he said during the talk. He noticed it everywhere and started writing his own at age 10 or 11.

Curtis said graffiti opened his world. In a city with strong territorial, cultural and racial divisions, he met graffiti writers from all over. He described graffiti as offering the artists — who, he stressed, were often children — a kind of passport to cross boundaries and connect with each other.

The Current’s main gallery is lined with 25 11-by-14-inch photographs of graffiti, which Curtis shot as a teenager in the mid-1990s. While many of Philly’s street-level tags were regularly cleaned up, he and his friends found troves in the subway system. “We started noticing graffiti dated all the way back to the 1960s,” he recalled. “It was kind of like going into an Egyptian tomb or some underground museum — this stuff existed still, and it was protected from the elements.”

-

Courtesy of Matt Neckers

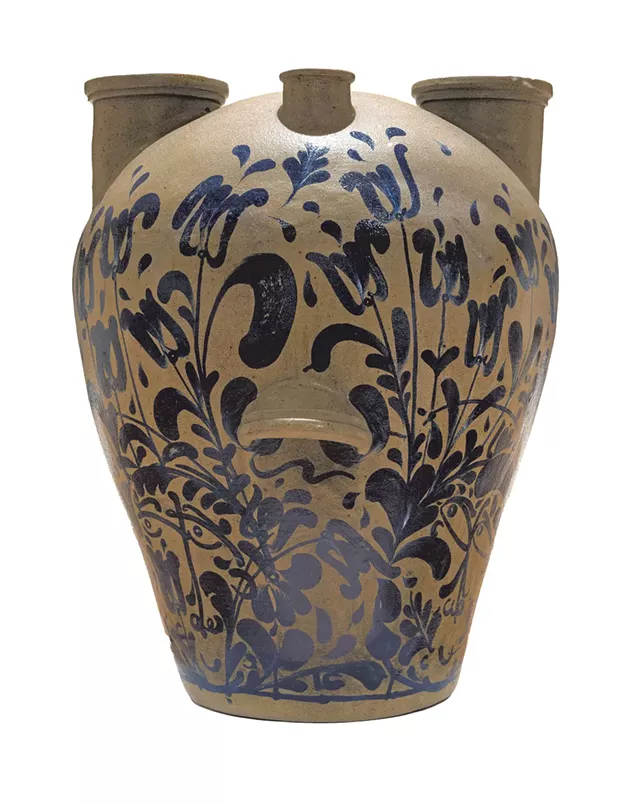

- “Philadelphia Mud Garden — 156 Years Later” Timothy Curtis

Many of the photos feature the taggers’ names, such as Cornbread, aka Darryl McCray, who is widely credited as the first graffiti artist of the modern era. McCray will offer a talk at the Current and visit local schools later in the exhibition’s run.

Curtis’ images document the Philly-specific elongated, gestural style of the tags — their lettering, curves, flourishes — as well as the recurring motifs, such as stars, crowns and top hats, that the artists added to their monikers. The artist’s thesis is that, stylistically, this graffiti is remarkably similar to another Philadelphia-based art form, one from a century earlier: Pennsylvania Dutch stoneware.

In the center of the gallery, Curtis has assembled “The Garden,” 19 pieces from his own collection of vessels, most dating from the 1860s. They are the colors of cement, shiny from a salt glaze, and decorated with deep-blue tulips, leaves, scrolls, stars and other embellishments. Curtis described how in Pennsylvania this type of pottery is ubiquitous: “It’s usually near the door of your grandma’s house, and there’s an umbrella in it.”

The style was created by German-speaking immigrants, some of them Amish or Mennonite, who came to Pennsylvania starting in the 17th century. It is generally associated with the countryside, but that’s an incomplete history, according to Curtis. Most of the pieces in the show were made in Philadelphia, many by Richard Remmey, a fifth-generation potter in the 1860s. “This is inner-city stoneware and pottery,” Curtis said. “It’s nice to kind of bring that back.”

In the Current’s west gallery, the artist presents a series of paintings that draw on both graffiti and pottery. Four 6-foot-square canvases and four 16-by-20-inch ones borrow visual elements from the stoneware: Each has a cement-gray base, not glazed like the pottery but with a sandy texture augmented by tiny flecks of pinkish glitter. Brick-red spots speckle the surfaces, a nod to the frequent marks and discolorations that occur when stoneware is fired.

Gardens of indigo tulips — like those popularized by Remmey pottery — burst forth in Curtis’ paintings, their stems stretching upward and arcing gracefully across the canvases. Showers of teardrop-shaped petals abound. The tulips grow over and around cartoonish round faces, whose expressions range from joyous to content to inscrutable.

His faces, Curtis said, are related to another Philly symbol: the smiley face. The yellow icon was created in 1963 by designer Harvey Ball in Worcester, Mass., for an insurance company based in Philadelphia; brothers Bernard and Murray Spain, who owned a chain of Philly-area gift shops, added the “Have a Nice Day” slogan and slapped it on buttons, mugs and T-shirts. Local graffitists then appropriated it for themselves, attaching it to their tags beginning in the late 1960s.

Curtis included similar faces in earlier works as a reference to those on prison feelings charts. Like pain-rating charts in hospitals, the icons are used as tools for prisoners to indicate their emotions when they might not be able to fully articulate them.

Curtis described how, in the new paintings, his faces are hiding behind the tulips, looking out at the center of the room, where he has situated a 30-gallon 1869 stoneware vessel. Curtis painted blue tulips and flourishes all over its surface himself, blurring the boundary between historical and contemporary art.

The vessel is a stand-in, he said, for his mother’s casket, which he also painted with Philadelphia tulips; she died six months ago. Her spirit is an emotional anchor for the elements in the show: Curtis described how she knew many of the graffiti artists whose tags are in his photos. His sense of Philly pride is clearly connected not only to the streets but also to his mother and her history. He chose to use this vessel, he said, because “she passed away in the neighborhood a few blocks away from where this potter is from.”

Curtis doesn’t think Philadelphia graffiti artists consciously learned from its potters, aside from an aesthetic possibly absorbed on school field trips. Instead, the connections he sees between them come from the way each medium is grounded in the place and how it was taught — father to son, as with the Remmey family, or older taggers to younger ones.

“It’s nice to have an American art form where people from poverty and certain class levels were connecting and bonding and doing it in style,” Curtis said. “A lot of this is taught in the streets or the jail system or the juvenile system — it’s not taught on an Instagram post or a YouTube video. You can’t do Philadelphia graffiti unless you come from this environment.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.