In the late 1980s a group of friends in Ladbroke Grove began combining the teachings of Islam with rap lyricism to birth an entirely new style

–

Among the bustling market stalls in 1980s Shepherd’s Bush in west London, there was a small group of teenage boys breakdancing and beatboxing, performing a cappella rap verses to passersby about class consciousness, racism and equality. They called themselves Cash Crew and, despite still being in school and yet to sit their A-levels, they were already pioneering a new form of British hip-hop that would go on to produce a bold scene of its own.

Breaking out of the long shadow of US genre originators, homegrown British hip-hop acts spent the late 1980s and early 90s tapping into their own culture to create a fresh sound. Brixton group Hijack developed a uniquely fast-paced hardcore style, while MC Rodney P delivered his verses in a distinct London accent. In their home of Ladbroke Grove, Cash Crew began combining the teachings of Islam with rap lyricism to birth an entirely new style: Muslim hip-hop.

“Hip-hop has always had roots in Islam, with rappers like Mos Def, Rakim and Ice Cube all being Muslim, but no one was doing what we were back in the early 90s,” Cash Crew co-founder Rakin Fetuga, 53, says when we meet on an icy winter’s night at his local arts hub, Rumi’s Cave, in Harlesden, north-west London.

In 1992, the group released a single titled The Provider, combining chants of “Allahu Akbar” over a thumping breakbeat, turntable scratching and horn fanfares, while MC Trim — Rakin Fetuga — espoused the virtues of an alcohol-free, halal lifestyle between mentions of the angel Gabriel and prophet Abraham. It was a bold move, especially considering that certain Islamic scholars believed all music was impermissible, while others unfamiliar with hip-hop might have associated it solely with the controversial and often violent lyricism of the gangsta rap dominating the US airwaves at the time.

Yet, The Provider was soon on regular rotation at taste-making radio station Kiss FM, as well as featured in the leading British magazine Hip Hop Connection, becoming the starting point for a niche but powerful genre of British rap that continues to this day.

“We were being open about our religion and combining it with the music — using it as an educational platform of self-expression,” says Fetuga. “We drew people in with the beats and then they got to know what we were talking about through our lyrics.”

Raised in west London to a Nigerian Muslim father and Christian mother, Fetuga began performing as a breakdancer in the 80s as hip-hop culture made its way to the UK.

“It all flowed naturally — breakdancing, graffiti and MCing,” he says. “We became really excited by the ‘conscious’ hip-hop movement that was happening in America at the time, with artists like KRS-One, Gang Starr and Brand Nubian all rapping about our Black history. It felt like an awakening and the more we learned, the more we wanted to be a part of it all.”

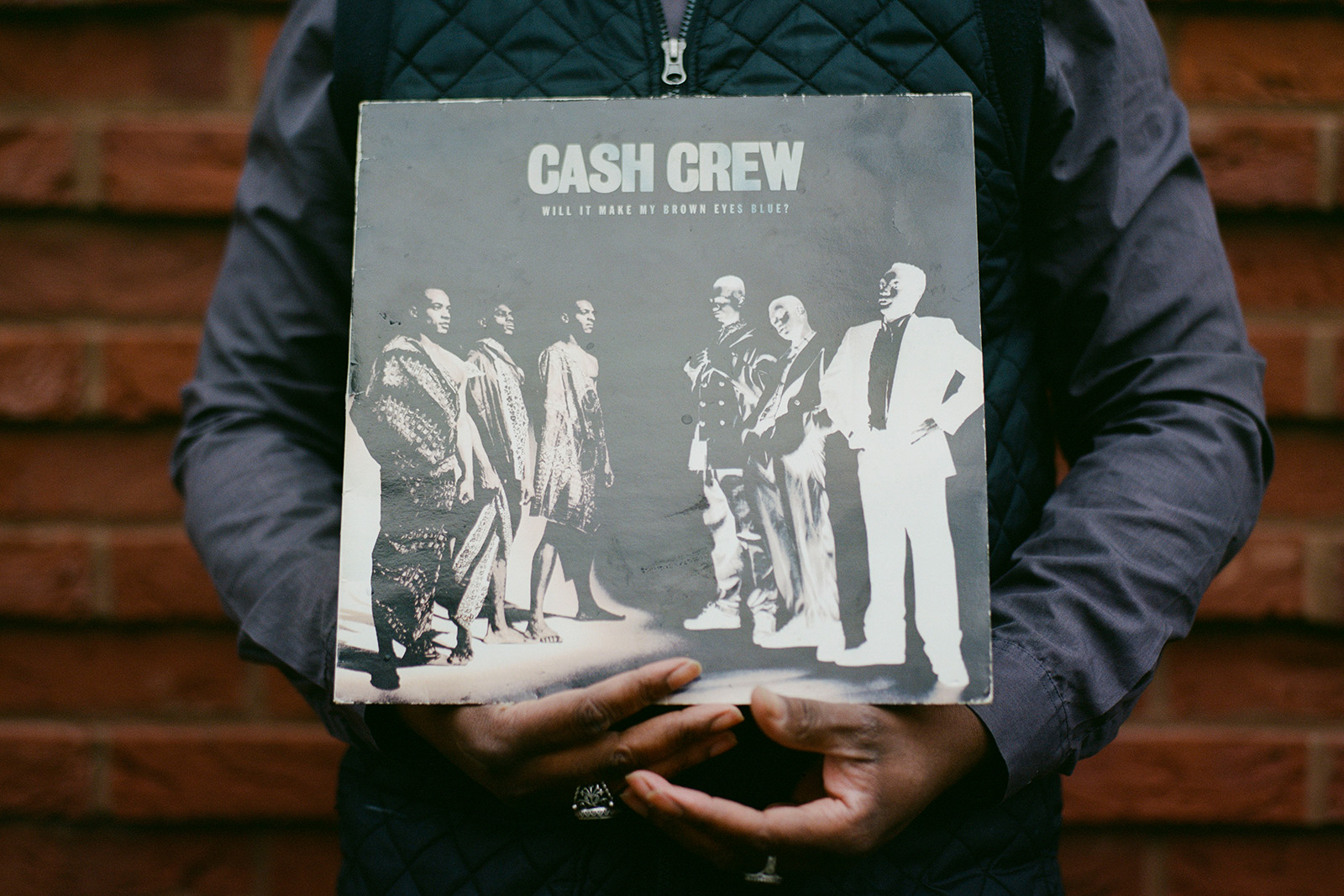

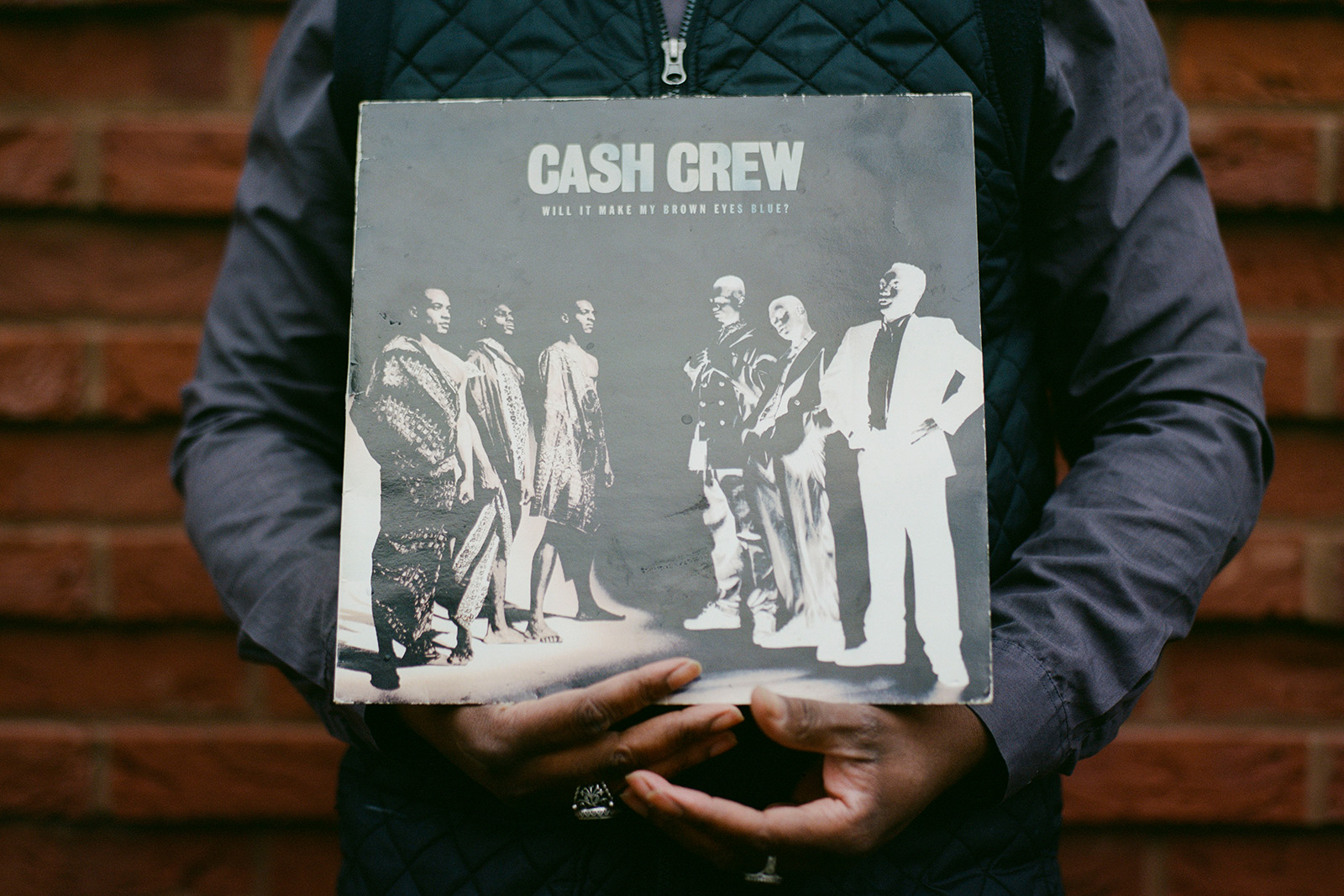

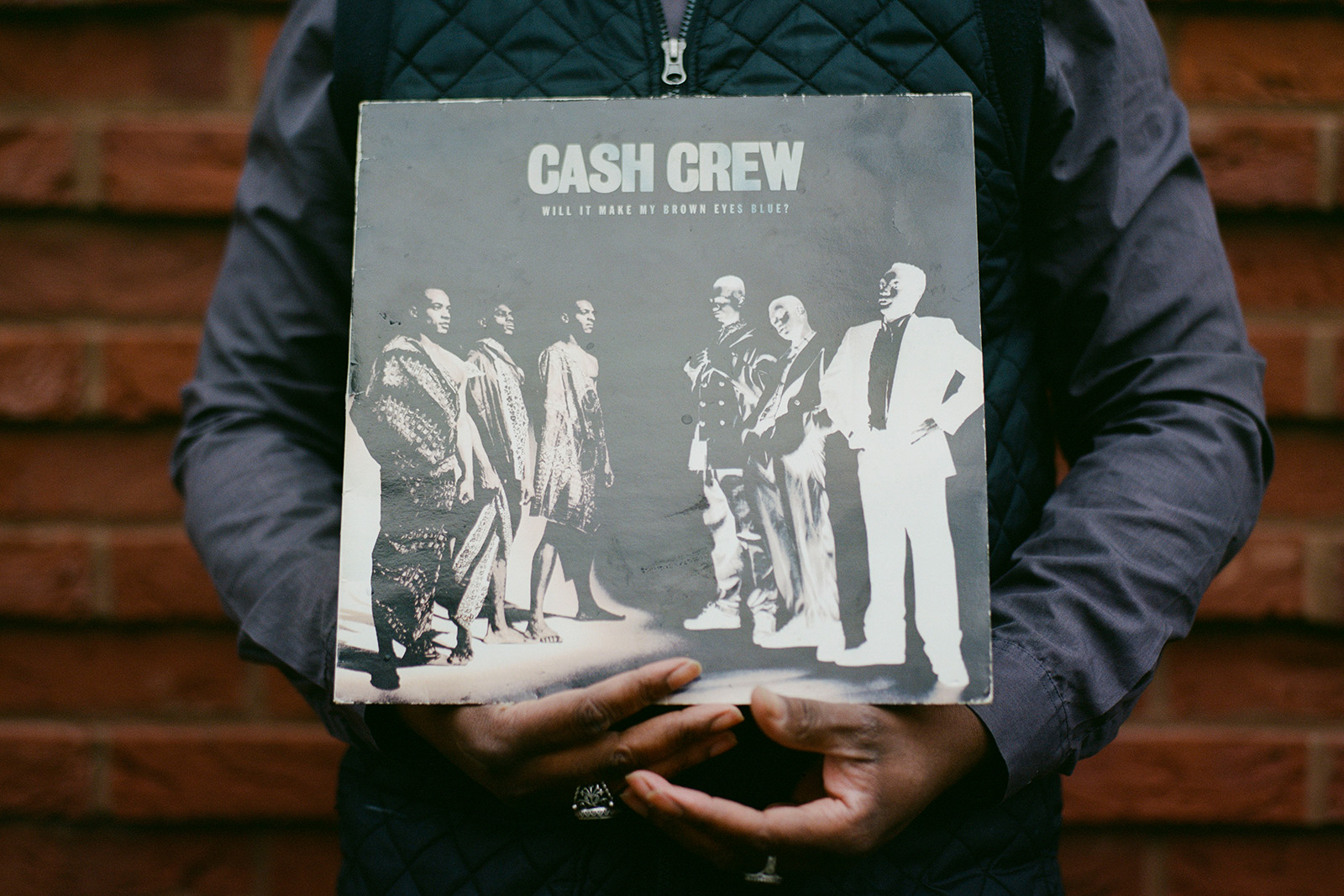

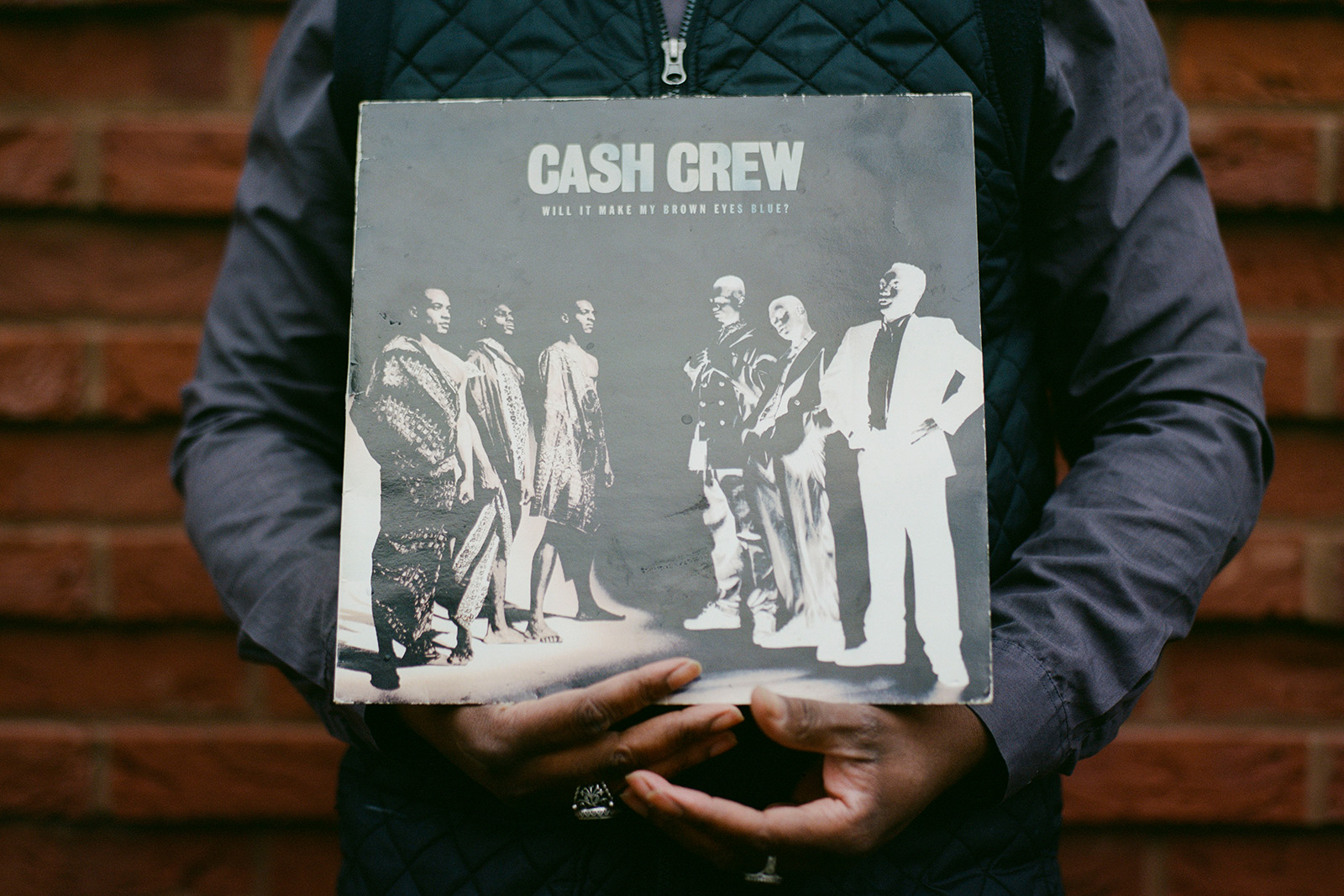

By 1985, Cash Crew were signed to Virgin Records off a handful of lo-fi demos. Still in school, they continued writing and performing, and were later flown out to the US to record material for what would become their 1991 debut album, Will It Make My Brown Eyes Blue? Covering topics that were otherwise unheard of in UK hip-hop at the time, the single Green Grass spoke about the climate crisis and threats to the environment, while Ghetto Circumstances critiqued social hierarchies.

“We became role models for the Ladbroke Grove community and everyone was really proud of us,” Fetuga says. After touring the album in 1991, however, Cash Crew weren’t able to recoup their advance and were dropped from the label.

The group converted to Islam in around 1992, and their faith “soon became part of our music”, Fetuga says. “That’s when we recorded and then independently released The Provider.”

The track was well received within the British hip-hop scene, “largely thanks to the tune’s heavy beat”, Fetuga laughs, but Cash Crew experienced severe backlash from the Muslim community. “Loads of people were calling us haram,” he says. “I remember one performance not long after the song came out when a guy ran on to the stage to attack us, but was luckily tackled off by security before he could. It was a scary moment and I think it was only later that we realised how dangerous it could have been.”

That incident forced Fetuga to question whether hip-hop and Islam could ever work together. He decided to leave Cash Crew in 1995, moved a few miles further north-west to the borough of Brent and began studying under the Islamic scholar Sheikh Babikir Ahmed Babikir, while finally sitting his A-levels.

But it was there that he returned to music, finding a path to forge his faith and artistry together. “The more I studied with my imam, the more he encouraged me to continue using Islam in my music. He taught me that music could not only be acceptable but actually an important way to keep educating others and have a positive impact,” Fetuga says.

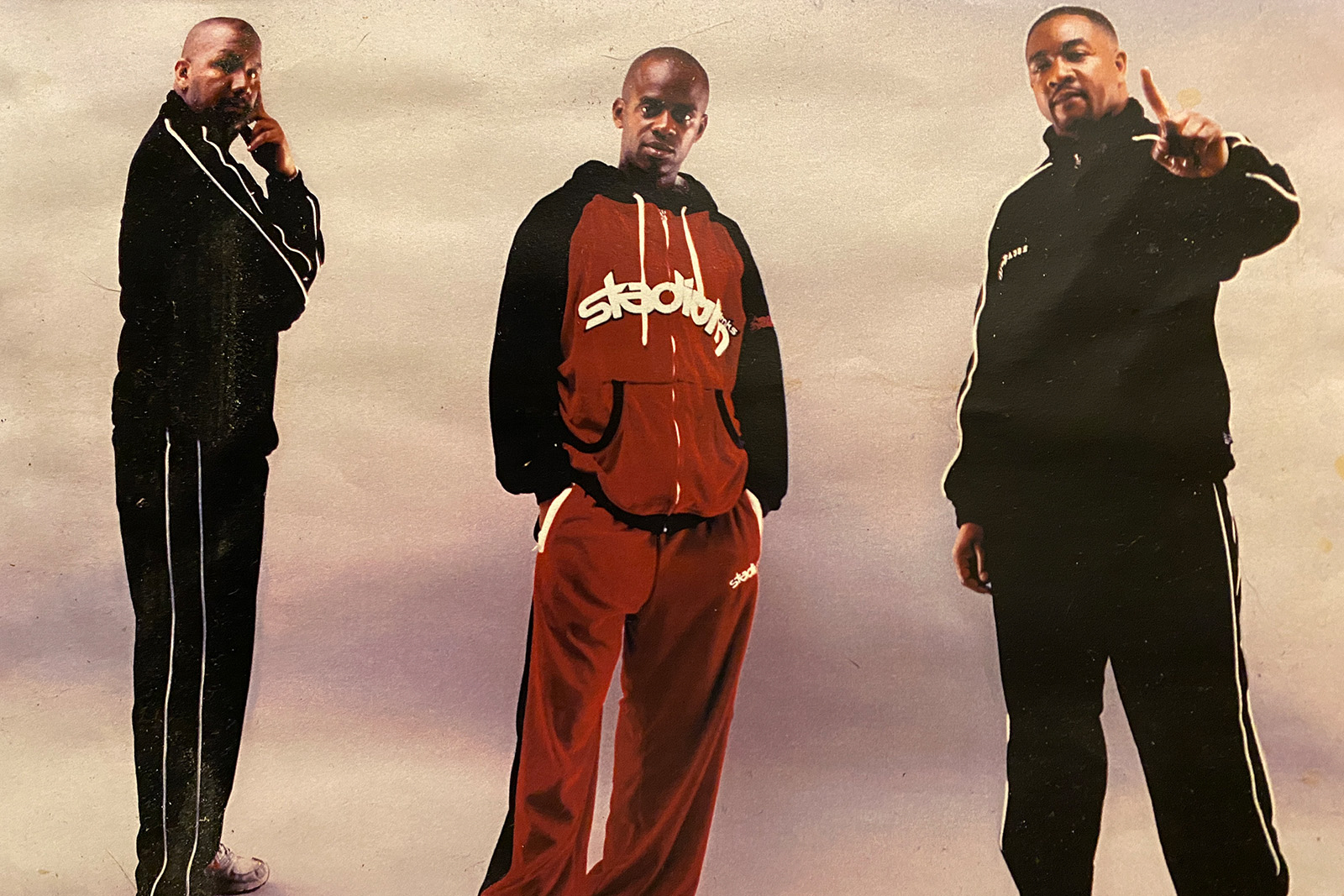

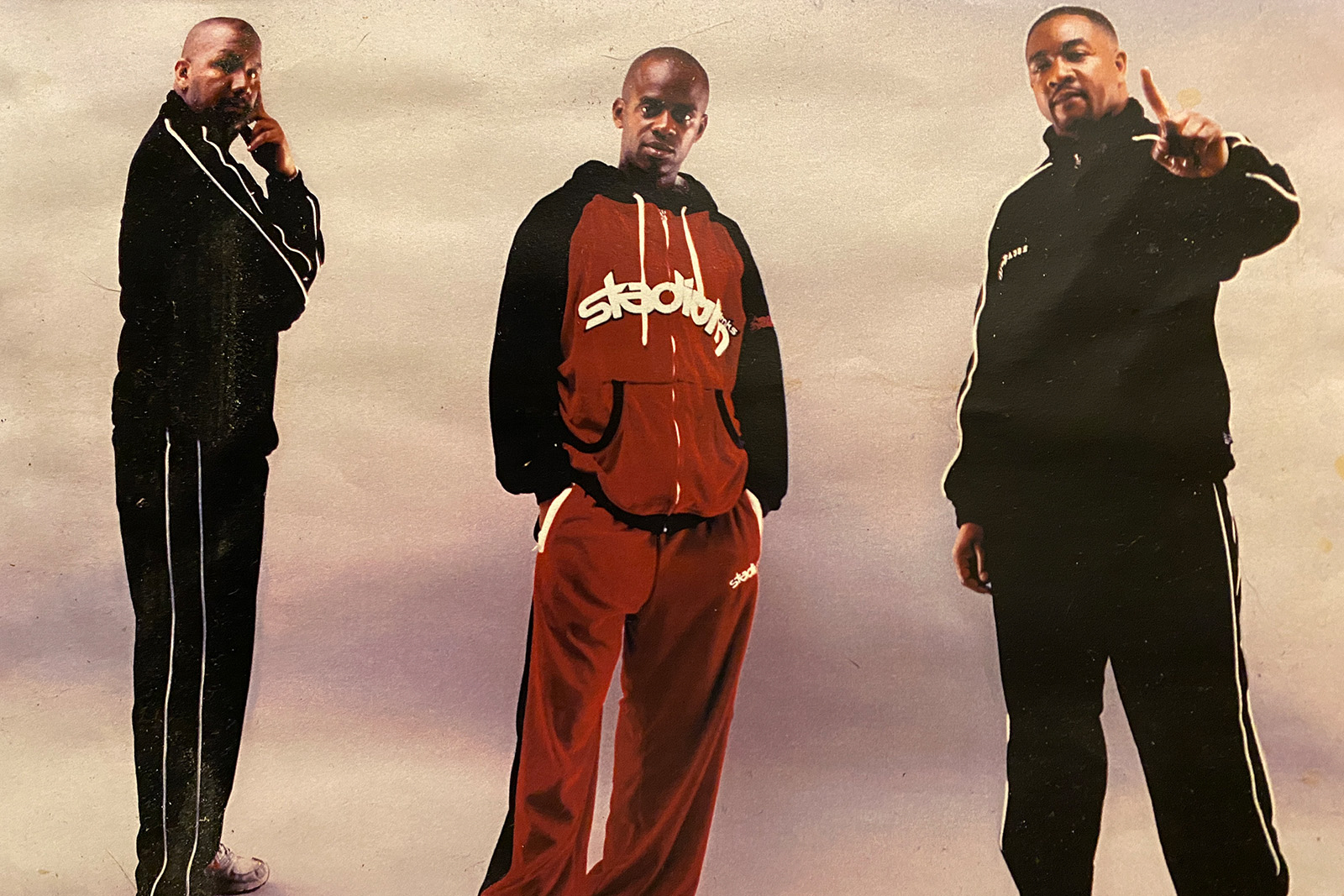

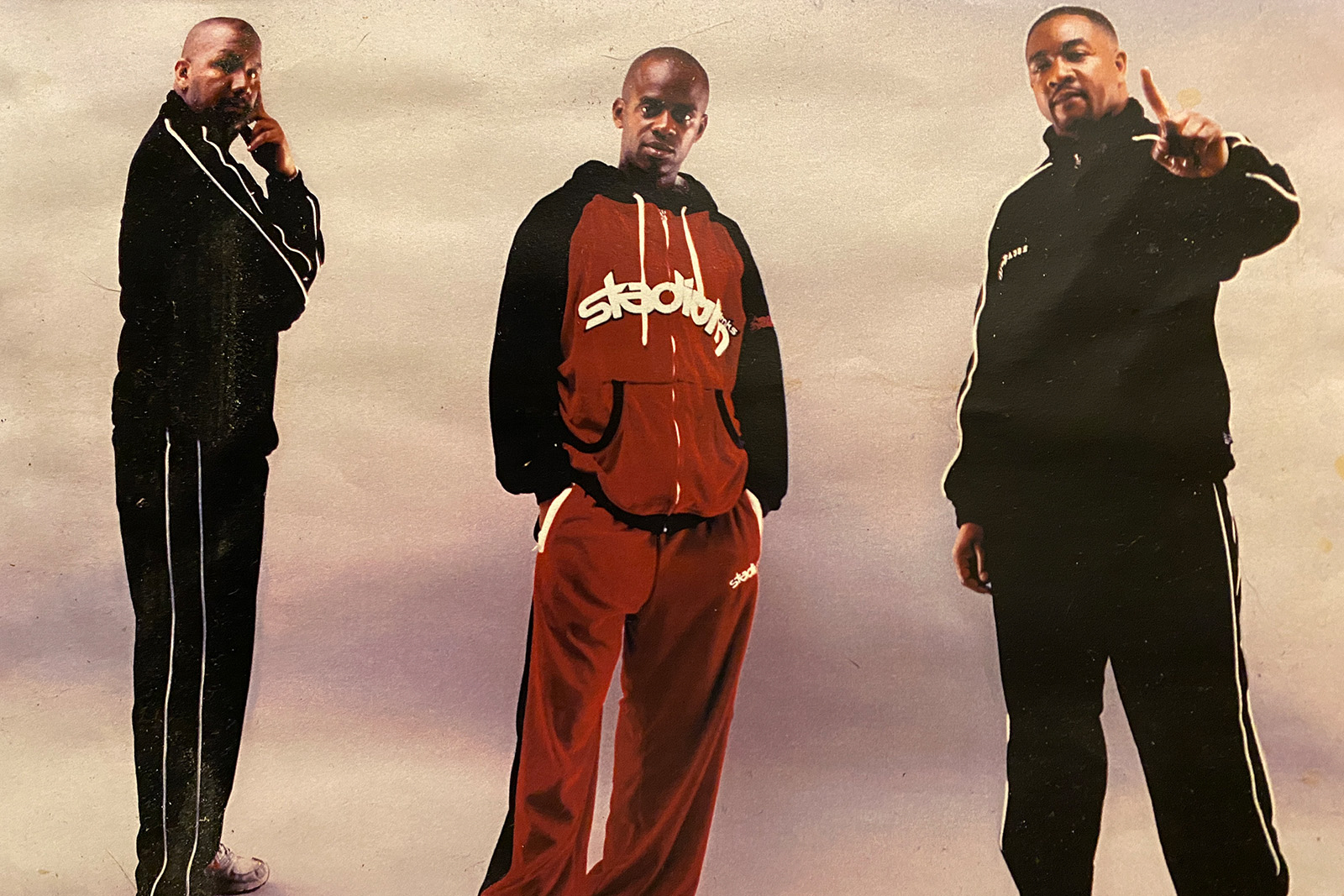

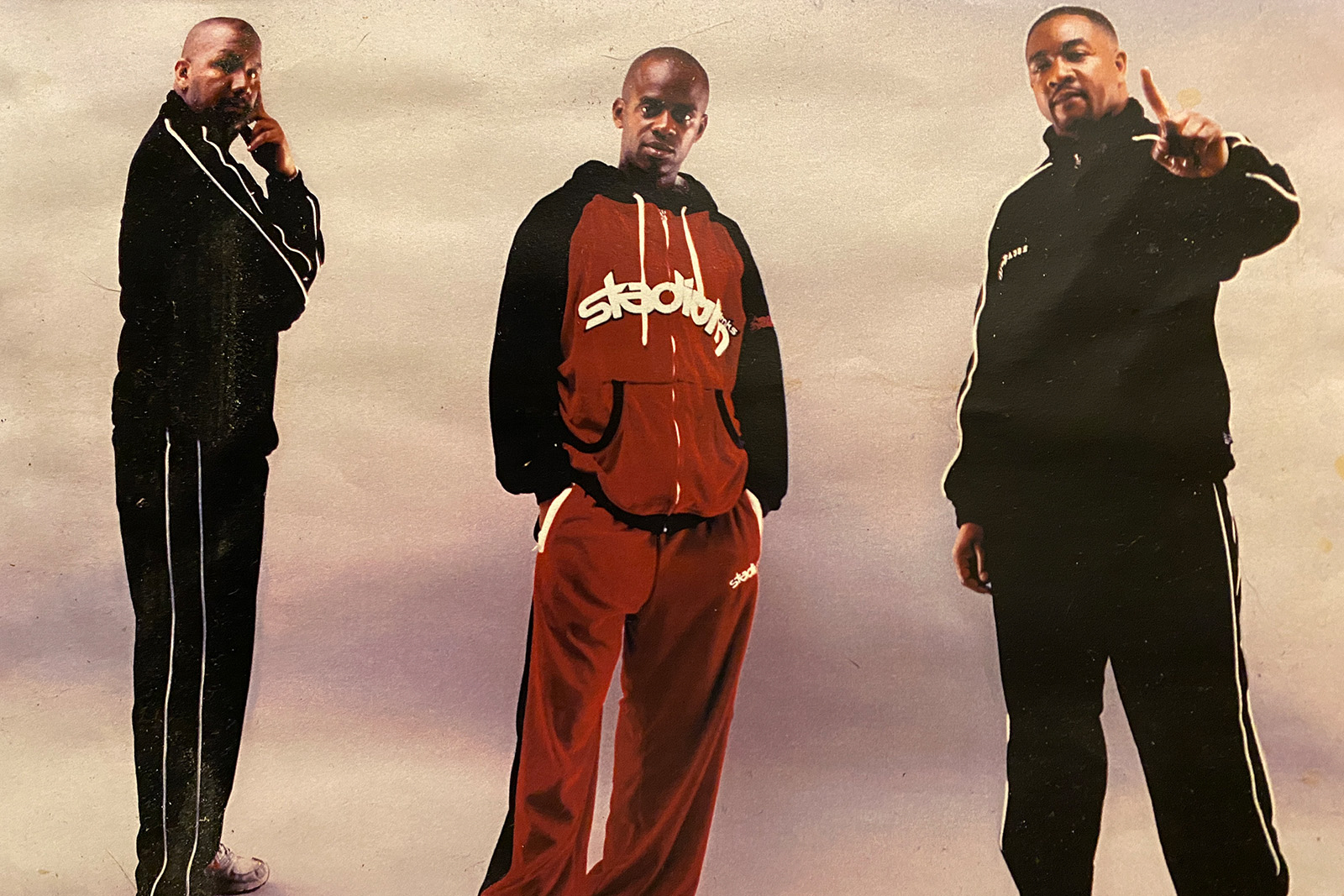

“That’s when I got together with another Muslim friend of mine who also rapped, Ishmael Lea South, and we formed Mecca2Medina — the first rap group in the UK that existed purely to make music about Islam.”

Releasing their debut EP, Life After Death, in 1996, Mecca2Medina began performing at melas, Muslim community events and at schools, aiming to spread the word of Islam through Fetuga’s combination of 90s boom-bap beats and socially conscious lyrics. While the group remained independent and underground, without commercial label support or mainstream radio play, their star was rising within the British Muslim community.

“They were trying to create a positive Muslim identity for us and making space for the next generation of Muslims to express themselves through art,” historian and writer Nadia Khan says. “Everyone in Brent knew them and they began to create a scene there — they’re pioneers.”

Younger rapper Mohammed Yahya, who was also based in Brent, was similarly inspired by Mecca2Medina when he was starting out.

“When my mum died in 2000 I went on a bit of a spiritual journey and on a trip to Gambia I met a beautiful community of Sufis who introduced me to Islam,” he says. “Once I was back home, a friend led me to a west London mosque where I converted and there I met Rakin, who immediately took me under his wing. Mecca2Medina influenced me to no longer make music that might imitate American rap, but rather art that spoke to my own experiences of Islam.”

The newly expanding group of Muslim hip-hop artists, including Yahya and groups Poetic Pilgrimage and Pearls of Islam, still faced criticism and controversy.

“We began to form our own scene, inspired by Mecca2Medina, and it felt really exciting to be a part of something new, but we still had cultural misunderstandings where people might listen to bhangra but they couldn’t fathom Muslims making hip-hop,” Yahya says.

“Or we had Islamic scholars still saying all music was haram. After 9/11 we also had so much more prejudice and Islamophobia — Poetic Pilgrimage had death threats, there was an arson attack and I once had eggs thrown at me outside a mosque during Ramadan. It was really tough.”

Facing threats of violence from some in the Muslim community and increased Islamophobia post-9/11, Yahya and the next generation of Muslim hip-hop artists ultimately became more determined to focus on their music, rather than waver in the face of criticism. In fact, the early 2000s was the point when British Muslim hip-hop seemed to find its biggest audience, sending Mecca2Medina, Yahya and others on nationwide tours.

“Strangely, it really took off for us after 9/11. We were getting so booked outside the Muslim community that we would sometimes perform in three cities in one day. It went that crazy,” Fetuga says. “We became the nice face of Islam and we made a lot of songs about Islamophobia, to show people there’s nothing to be scared of.

“We ended up being featured on BBC Radio and we regularly spoke to government outreach programmes. It was hard to tell what impact it might have had but I think it was important that our voices were heard and our faces weren’t seen as a threat.”

Navigating wider popularity alongside increased scrutiny and potential danger eventually served to galvanise the musical community. “I decided to start a monthly event where we could represent ourselves and invite a young crowd into a safe space,” says Yahya. “Alongside Poetic Pilgrimage, we set up the night Rebel Muzik at the Ladbroke Grove pub Inn on the Green in 2006 and it became a hub for Muslim poets, rappers and singers to develop their talent. People like Lowkey and Muslim Belal would come through — it was one of a kind.”

Facing rising rent and rates, Inn on the Green closed in 2011 and Rebel Muzik followed. Yahya went on to found the Muslim Jewish duo Lines of Faith to promote religious tolerance in schools and now leads a programme about hip-hop and environmentalism, Hip Hop Garden, in Bristol.

In Brent, Fetuga became the artistic director of Harlesden community restaurant and arts centre Rumi’s Cave. “We run lots of spoken-word events here now as that seems to be where the young community are really expressing themselves,” he says from the bustling restaurant floor. “With all the war and genocide going on in the world, the young people need a way to talk about their realities and there still needs to be more education about Islam — we can’t continue to be seen as the enemy. Mecca2Medina created a scene but new artists need to take up the mantle now.”

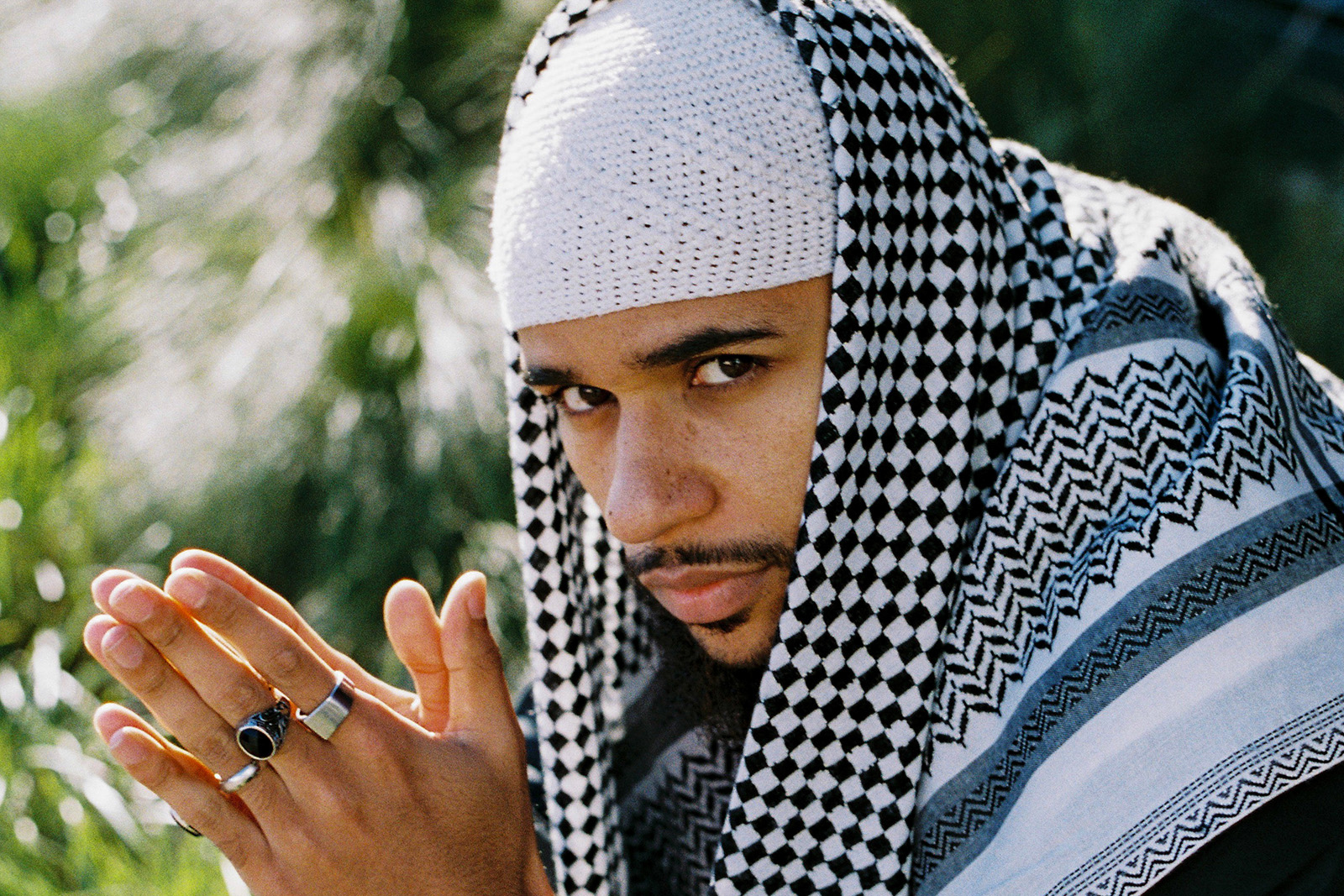

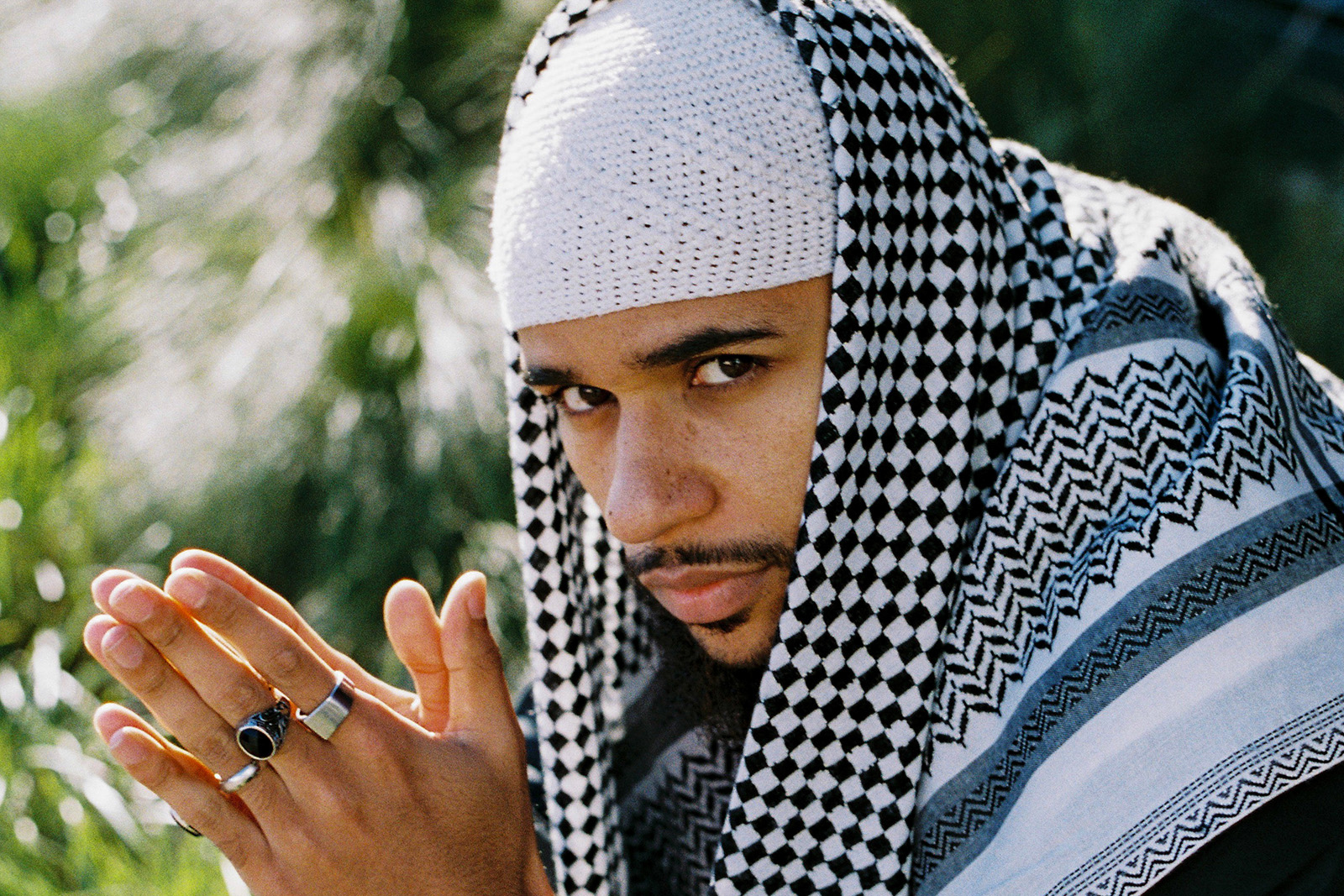

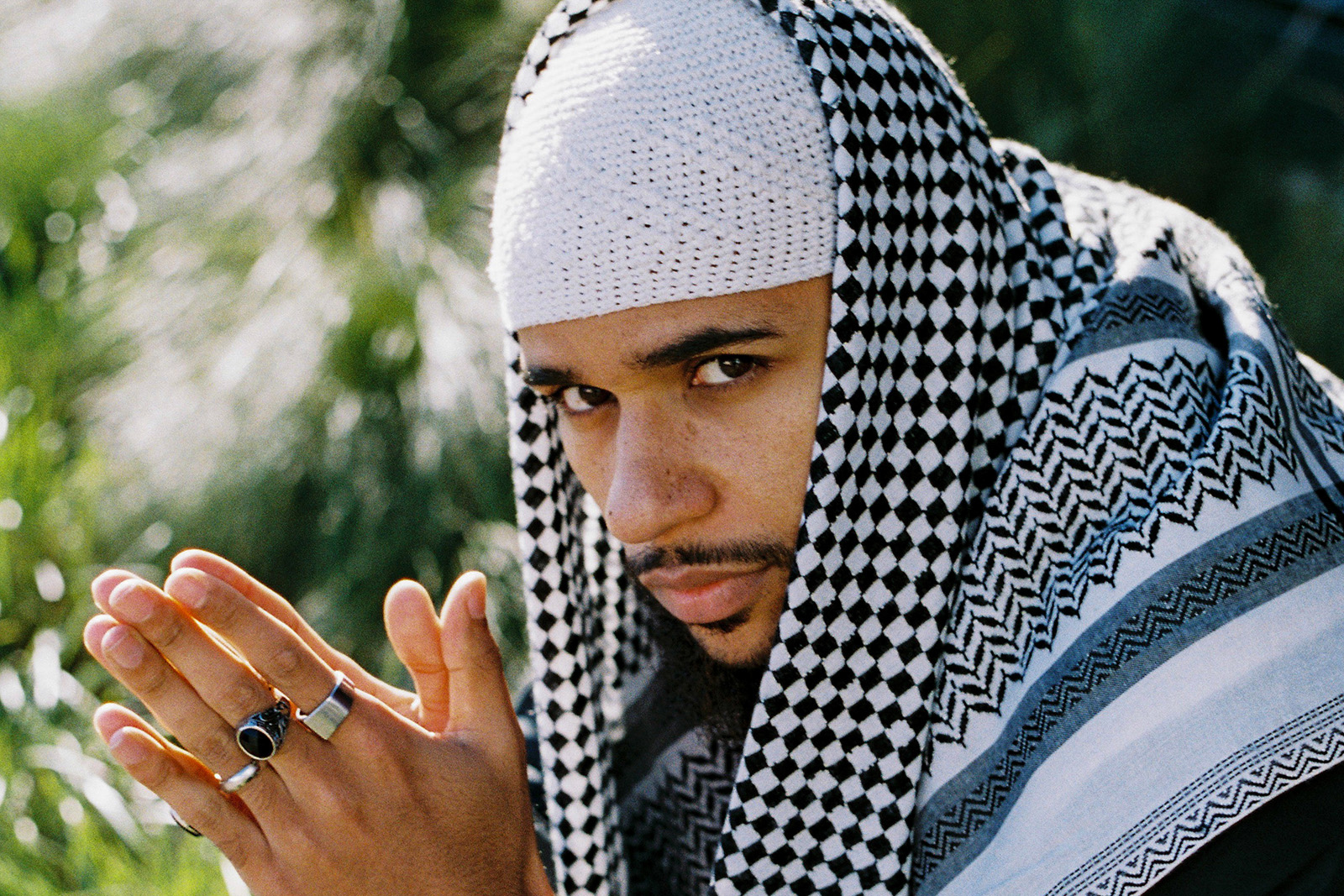

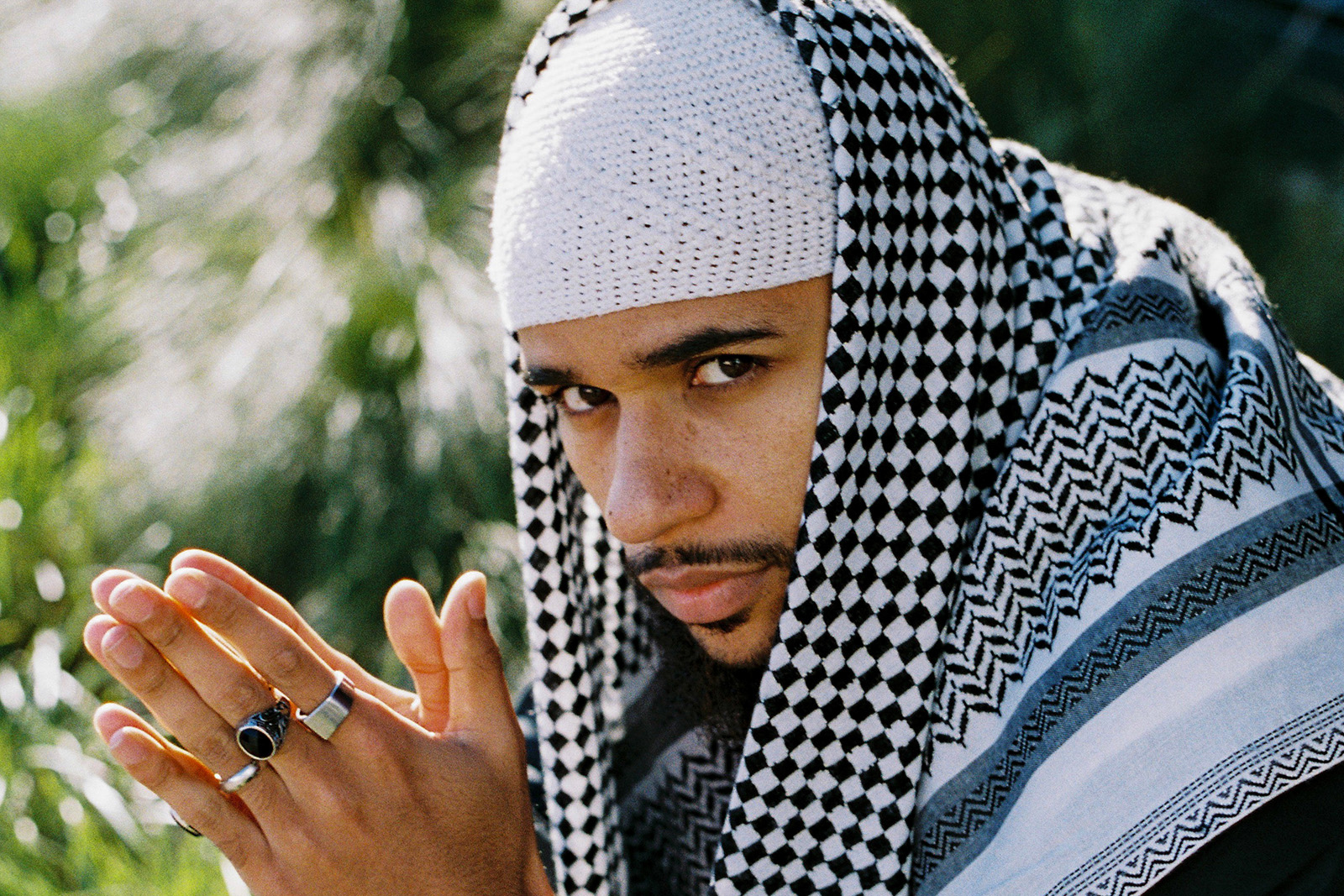

One of those artists is London-based Khaled Siddiq. Making music since he was 14, Siddiq began posting nasheed songs on YouTube in 2015, before quickly expanding his output to include everything from folk to rapping over drill beats — all while including messages about Islam to his 300,000 subscribers.

“Islam is open and beautiful and this music has a rich history that people don’t know about, from Mecca2Medina onwards,” he says. “There is still backlash, but it comes from ignorance and I just want to pave the way for more Muslim artists to come through and spread their positivity. The Christian gospel scene is massive, so why can’t we do the same with our own music?”

More than 30 years on from the origins of Muslim hip-hop in the UK, with artists such as Siddiq finding a young social media-based audience and Fetuga developing a documentary on his career, the legacy of that niche west London scene lives on.

“We have our place in history but I think people are always ready to hear new sides of Islamic culture,” Fetuga says. “The time is still ripe for this music.”

Topics

Get the Hyphen weekly

Subscribe to Hyphen’s weekly round-up for insightful reportage, commentary and the latest arts and lifestyle coverage, from across the UK and Europe

This form may not be visible due to adblockers, or JavaScript not being enabled.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.