It’s ironic that the earliest synonym for street art in India was ‘vandalism’. In the early 1990s, at the dawn of mural culture in the country, graffiti was seen more as a nuisance than a form of expression. In cultural hubs like Bombay and Delhi, graffiti emerged sporadically, only to be painted over. Yet, much like the authoritarianism it often opposed, it returned—stronger and more defiant. In Bombay, Bandra’s Chapel Road became an informal epicentre of graffiti, featuring bursts of cartoon characters, hype slogans, and abstract imagery by local artists. Following the 1992 riots, walls in South Mumbai—Colaba and Marine Drive in particular—were transformed into canvases for anonymous protest art and commentary. In the capital, the walls of Central Delhi and North Campus of Delhi University reflected the city’s activist heartbeat, filled with slogans and imagery tied to student protests and political campaigns. Hauz Khas evolved into an experimental hub for young artists while Bollywood-inspired murals and slogans began appearing across Connaught Place and Karol Bagh.

“When I first arrived in Delhi in 2005, graffiti in this sense was virtually non-existent (at least visibly),” says street artist Bond Truluv. “There were only a few local interpreters who have been practising graffiti writing on the walls of the main urban settlements—but that made it more interesting to paint here. Graffiti-writing is not perceived quite as negatively as it is in western society,and I experienced mostly positive reactions when painting on the streets. Also the powerful spiritual atmosphere, diversified landscape, the lack of spray cans (and therefore forced improvisation), and the friendship with the few existing Indian writers made painting in India a unique and beautiful experience for me.”

Street art remained largely underground until the 2010s, when festivals like the Delhi Street Art Festival and the St+Art India Festival began bringing the movement into the limelight. Gradually, government support followed, and murals began to carry directed messaging. “In the early days of street art in India, I collaborated with pioneering artists such as Zine, Daku, Yantr, and Sunone,” says artist Zake.“At that time, only a handful of us were painting on the streets across the entire country.” It’s a community that constantly feeds into each other’s work.“I draw inspiration from a variety of artists; a few I really admire at the moment are Arsek & Erase, James Jean, Sofles, and Bond Truluv.” The street artist’s work embodies a sense of liberation that can range from bohemianism to outright dissent. It calls for an adaptability that studio art may not. “The streets are alive with a public audience as you paint,” says Anpu Varkey. “Sometimes, you’re literally suspended in mid-air while working, physically and emotionally drained from the long hours.You work fast, and intuitively, always racing against the sun, which is constantly behind you.Your audience could be thousands of people, passing by every day. I’ve had entire metro crowds in Gurgaon stop during peak commute hours just to watch me paint. People even bring their kids to watch. Those moments stick with you.” For Varkey, this connection with a live audience, unmediated by galleries or institutions, is palpable and deeply meaningful. “I’ve been invited into people’s homes, given food and drinks while working. There’s something exciting about being on the streets—you never know who you’ll meet or what story they’ll share, or what you’ll paint. I’ll never grow tired of it.”

Kartikey Sharma started street art as a means to make a living.“I didn’t have a good relationship with my dad, and I found myself disinterested in my engineering internship. I started convincing small cafe owners to let me paint their walls with pretty images, but I wasn’t very successful,” he chuckles. Over time, he found himself drawn deeper into the world of street art. “I love creating murals that make people wonder,‘How did they even do that?’ Using cranes, scaffolding, harnesses, and industrial equipment, I aim to show the endless possibilities in art and in life.” He stayed in it long enough till he conceded he was in too deep—and the slow, gradual love for it took over.

The surreality of his start—choosing art over engineering to make money—reflects in his work.For graffiti artist Raj Pathare, better known as ‘Mooz’, lettering is a form of self-expression, one that says ‘I was here’.“It’s a challenge to do the same letters in a different style while maintaining an essence of yourself that is unique. Graffiti is very new in India– people often consider anything written on the wall graffiti, but it’s not.” He also points that while street art feels anarchic, it actually relinquishes a lot more control than most other art forms.“When you paint on a canvas or book,the artwork stays with you.You have control over the medium, over your painting. But painting in the street means leaving the artwork there. Someone could scribble over it, pee on it, spit on it, destroy it altogether. When you do something digitally or on canvas, you know you’ll preserve it. Here, it’s a gamble.” Truluv echoes this sentiment, saying he prefers the physicality of street art to the confines of a studio. “Also working inside the studio with solvents, ventilation is always an issue, especially when it’s cold outside.And I love spray paint for its handling; even for very small pieces. It dries faster and covers so much better than any water-based acrylic. I am constantly astonished how much spray paint technology has evolved. Standing in front of a large scale ‘wall of colour’ that is larger than the spectator, hearing the sounds of the area and feeling the whole vibe of the experience is always special.”

Zake believes it takes gumption to be a street artist. “You need to step out and do it.” Easier than you think, he says, but harder than you know. It comes with being perennially prepared for whatever could go wrong. “Sometimes it’s dealing with the authorities, other times it’s the people. Interestingly, both can occasionally be helpful, too.” Varkey agrees. “Back in the day, there was nothing set up for us.We simply walked around and asked people for walls to paint on, and it happened. If you want to paint on the streets, don’t wait for someone to offer— go create them. Just paint.” Of course, public art has its challenges. “There is often criticism when outdoor spaces are painted, and it can be disheartening to constantly explain why I cannot always create ‘pretty’ things. Artistic expression is often judged more harshly when it is displayed publicly because, as an artist, you are left vulnerable in that moment.”Pathare also points out the double-edged sword of a town being your canvas.“It’s kind of selfish, because you’re doing something on private property, but selfless, because you have to leave it there.You can’t take it, you can’t scrape it out of the wall. It doesn’t fully belong to you.”

The thread that runs through the community is a love for the freedom and anarchy of the medium; a community that grew, in no small part due to organisations like The Wall Project (Mumbai), Kochi Biennale Foundation and of course, St+Art India, that put their back into bringing the medium to the forefront.“St+Art made a difference. They showed the country that painting streets can be good for society. I have seen that change happening right in front of me. Because of them, the elite started hiring street artists to paint their personal properties. Many large industries then brought this kind of work into their office and on their factory facades. All these people gave us push. We started having the income to explore our own self as an artist.” Truluv emphatically agrees. “The St+Art India foundation was responsible for many amazing projects, promoting and pushing street art and graffiti all over India.” It’s why the passing away of Hanif Kureshi, co-founder of St+Art, late last year hit the community so hard. But it was also a reminder of how much the street art scene had blossomed over the years and how much it mattered. From being treated like an aesthetic plague in the late 90s to being given patronage to brighten up cities, the form has seen a mammoth growth. The next stop? A world stage. “Our artists are travelling and representing India on the world map,” says Sharma. “Indian street art is part of the conversation. More artists will be able to sustain themselves through art as demand increases which helps them travel and paint across the world. All that any artist wants is the opportunity to keep learning. And travelling will do that.”

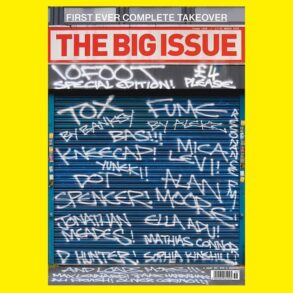

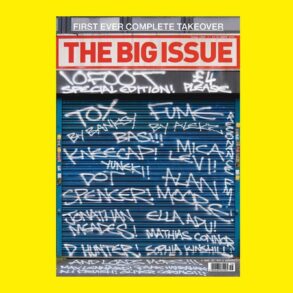

Lead image: .Potntial

This piece originally appeared in the Januar-February print edition of Harper’s Bazaar India

Also read: At Serendipity Arts Festival, art comes alive through movement, music, and food

Also read: Guardians of expression: India’s pre-independence art galleries and their lasting legacies

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.