Though the current structure dates to the Crusader period, its associations with the Last Supper, Pentecost, and other events in the life of the early Church have drawn pilgrims for generations.

A groundbreaking study of medieval graffiti in the Cenacle — the traditional site of the Last Supper in Jerusalem, the Upper Room — has revealed an extraordinary tapestry of Christian devotion. Using advanced digital imaging, researchers have identified nearly 40 inscriptions and drawings that attest to the wide range of pilgrims who visited the site between the 13th and 15th centuries.

Among the discoveries are coats of arms, Arabic and Armenian inscriptions, and devotional sketches left by travelers from as far as Austria, Armenia, and Syria.

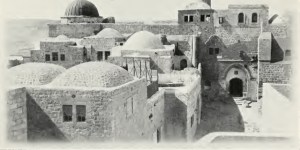

Located on Mount Sion, the Cenacle is one of Christianity’s most venerated spaces. Though the current structure dates to the Crusader period, its associations with the Last Supper, Pentecost, and other events in the life of the early Church have drawn pilgrims for generations.

Now, a collaboration between the Austrian Academy of Sciences, the Israel Antiquities Authority, and Armenian scholars has brought to light inscriptions long hidden beneath centuries of dust and limewash.

Among the most striking is the coat of arms of Tristram von Teuffenbach, a Styrian noble who accompanied Archduke Frederick Habsburg to Jerusalem in 1436. The stylized crest confirms his participation in one of the era’s best-documented European pilgrimages.

A King’s Christmas and a woman from Aleppo

Other finds illuminate lesser-known chapters of Christian history. An Armenian inscription dated “Christmas 1300” likely celebrates the entry of King Het’um II into Jerusalem following his military success in Syria.

Nearby, a partially preserved Arabic inscription includes a rare grammatical marker suggesting it was carved by a Christian woman from Aleppo — one of the few known examples of female-authored pilgrimage graffiti from this period.

A second coat of arms, almost identical to that of modern-day Altbach in southern Germany, was found alongside drawings of a goblet, platter, and round bread — possibly a Eucharistic reference, or even a nod to Jerusalem’s traditional sesame bagels.

A mosaic of faith across borders

While Western pilgrims have often dominated historical narratives, the graffiti tells a broader story. The article published by Medievalists.net explains that many of the inscriptions are in Arabic and reflect the piety of Eastern Christian communities.

Serbian, Czech, and German names also appear, including that of Johannes Poloner of Regensburg, who recorded his journey to Jerusalem in 1422.

The research team employed cutting-edge techniques such as multispectral photography and Reflectance Transformation Imaging to reveal markings invisible to the naked eye. These methods were refined at the Leon Levy Digital Library, where data from various imaging sessions were digitally enhanced and merged.

One carved inscription honors Sheikh Aḥmad al-ʿAgamī, a key figure in the Cenacle’s later Islamic history. It was he who persuaded Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent to expel the Franciscans in 1523 and convert the site into a mosque — evidence of the hall’s layered and contested legacy.

What emerges is a complex, deeply human portrait of a sacred space. The Cenacle was not just a monument of faith, but a crossroads of culture, politics, and devotion — a place where pilgrims of every kind left their mark, quite literally, on history.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.