When Simon Durban, an art curator and collector, entered my apartment during Chol HaMoed of Pesach (the weekdays of Passover) and glanced at the walls, I dared not guess what was going through his mind. After all, this was the man who had spent 15 years managing the global business empire of Banksy, the anonymous graffiti artist whose activist, subversive, socially conscious works are internationally recognized.

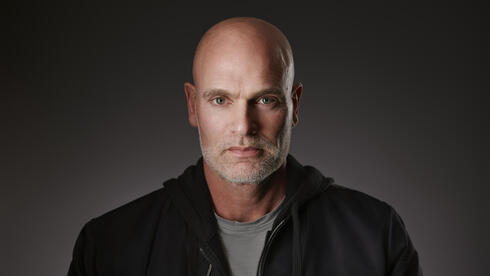

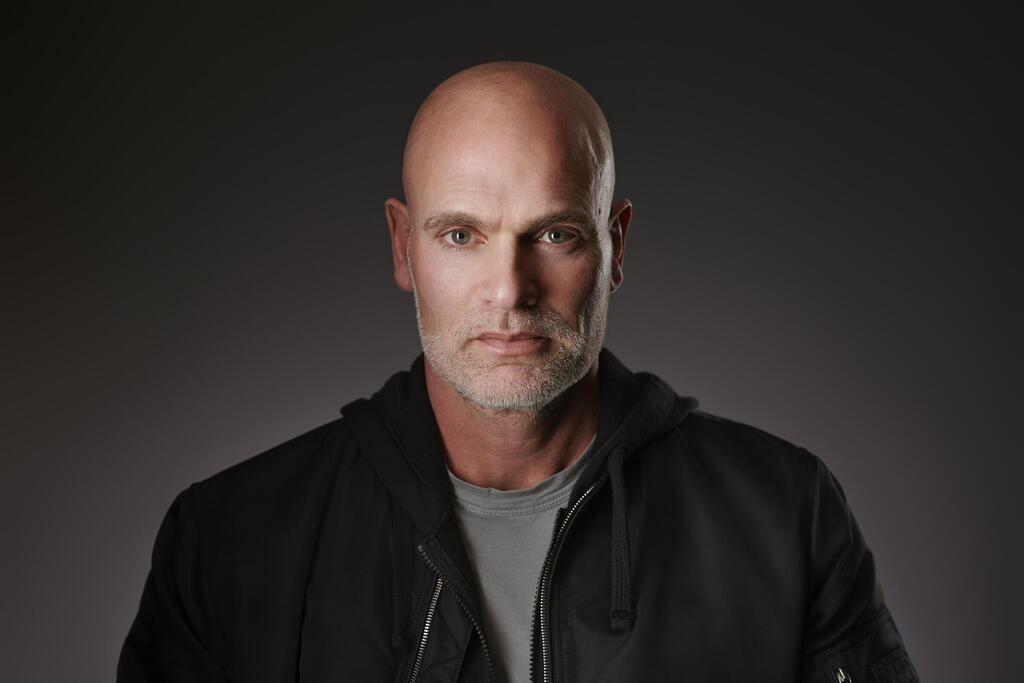

Durban, 54, was born and raised in London to a Jewish family. He is divorced and the father of three children, ages 25, 22, and 18. In an exclusive interview, he shared about his personal and professional life, crediting much of his path to chance encounters and to the Zionism that runs in his blood. “I grew up loving sports, especially football and cricket, and being Jewish. When I first visited Israel at 18, I knew this country would forever be a part of me,” he said.

Durban did not study art but rather earned a degree in accounting and economics. After two years in the field, he realized the profession wasn’t for him and pivoted to the music industry. One day, he heard about a young street artist designing record covers. “I was advised to meet the guy, telling me his name was Banksy, and that he was going to be something big.” Durban took the suggestion seriously and met Banksy at a party in Ibiza. “They introduced me to him as someone who could help manage his affairs. We clicked and started working together.”

EXHIBITION 07SH10AH23

(Video: ILTV)

The British Banksy is widely regarded as one of the most outstanding graffiti artists in the world. An elusive, invisible artist whose identity has never been confirmed despite years of speculation in both British and American media. His work, which includes sculptures and unique installations, can be found on walls, bridges, and urban streets around the world.

“The first thing I remember from Banksy happened on our first meeting,” Durban recalls. “I was taking notes and, innocently, wrote the name ‘Banksy’ on a piece of paper. He saw it and said, ‘Never write the name Banksy on any paper,’ and asked me to erase it. I was very cautious in protecting his anonymity from that point on. That was the hardest and most important part of my job – living under that pressure, accompanied by huge responsibility, knowing that one mistake could be critical.”

Durban worked with Banksy for 15 years. Just three months after they started, Banksy decided to relocate to Switzerland. “Another opportunity came up”, Durban smiled. “I told him I could represent him best there. We were on the road to success. From then on, everything we touched turned to gold. Every project he did exploded in popularity.”

During the years, Durban was present when Banksy pulled various tricks, including the most famous one in October 2018 when Banksy’s “Girl with Balloon” self-destructed via a concealed shredder just seconds after being sold at auction for over £1 million. Sotheby’s later renamed the piece “Love is in the Bin,” and sold it in 2021 for $25 million. “That first sale will be forever treasured in art history,” said Durban. “It was brilliant, a trick no one will forget or replicate, and certainly no other artist could outdo.”

If it was so interesting and rewarding, why did you leave?

“About six years ago, just before the COVID pandemic, I decided to take time for myself.”

Durban parted ways with Banksy, owning 60 of the artist’s pieces. During the COVID pandemic, as he had realized that the prices of art pieces soared, he sold 40 of them.

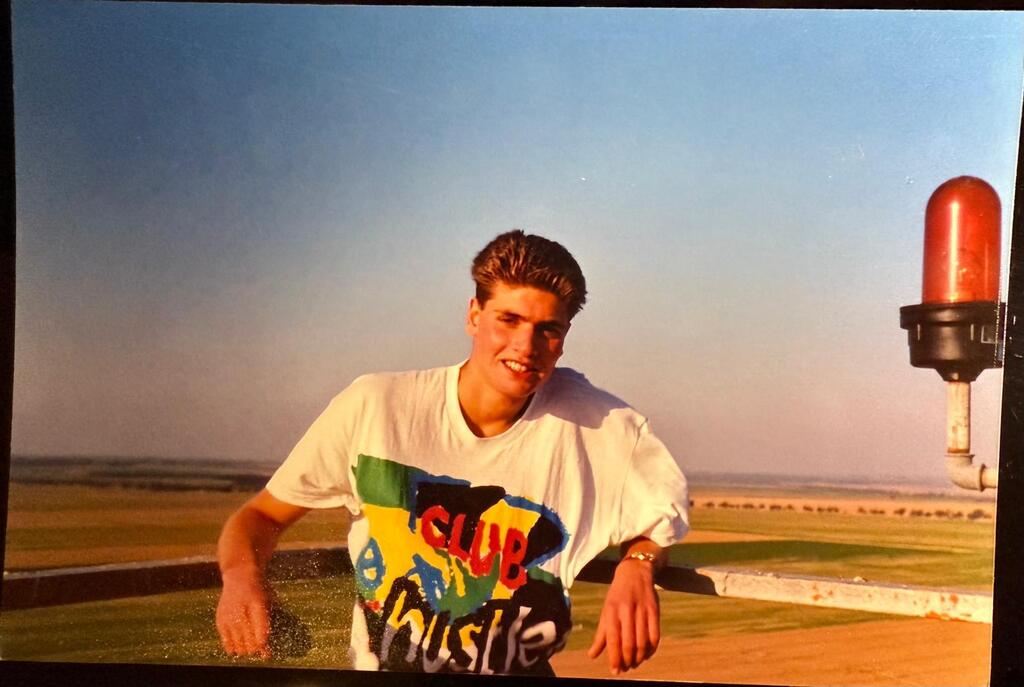

Throughout those years, Durban never lost touch with his Jewish roots and gradually began embracing his Israeli identity. His first visit to Israel was in 1989, at age 18, as part of a youth delegation. He volunteered at Kibbutz Magen, located near the Gaza border, 34 years before returning to the same place after the October 7 massacre. “Something happened to me on that trip,” he recalled.

“Spending three months on the kibbutz, I felt a kind of spiritual awakening. One day, I got on a bus to Jerusalem on my own and was mesmerized by the hills near Sha’ar HaGai. Even then, as a volunteer, I felt deeply connected to the land. I always knew I’d live here one day. Especially after October 7, making Aliyah these days just feels natural to me. Logically, it’s hard to explain my bond with Israel.”

His visits to Israel continued even after he married and dived into his career. In 2007, he traveled to Israel with Banksy, who is not Jewish, as Durban stresses, and they headed for a trip to the West Bank.

“I’d rather not elaborate on that,” Durban said after a pause. “I’ll just say that Banksy always wanted to side with the underdog. I remember the visit as an incredible, albeit slightly frightening, experience. While we were there, Hamas held a parade at the square, and their leader walked around with a machine gun on his shoulder. We entered a shop, shut the doors, and hid inside.”

The two returned to Israel during Operation Protective Edge in 2014, when Banksy painted in Bethlehem and Gaza. “I remember Hamas launching indiscriminate rockets into Israel and hitting civilians,” Durban said. “After the operation ended, Banksy and I planned to enter Gaza. He wanted to paint there because it was dangerous – he always sought out places no one else had created art in before.”

What do you remember from that trip?

“Our contact person arranged a cover story for us, but I was terrified the entire time. For example, we needed permits to cross through the Erez checkpoint. Even though I thought I could easily hide my Jewish identity, I was still afraid of being killed, arrested, or something happening to Banksy. My biggest fear was flying out of Ben-Gurion Airport and getting interrogated by Israeli security. For me, being in Gaza after the military operation felt like I was betraying my religion, my beliefs, my people.”

Durban’s success, he said, often stemmed from chance. “I split my time between Golders Green and Stamford Hill. It was a ‘hand-to-mouth’ existence. One day, a pension adviser I met, who must have seen something in me, introduced me to a Jamaican man who ran a record label in West London and was looking for a financial manager. That’s how I met Peter Harris, who owned a boutique records label in WestWay, a colorful cultural melting pot. We started working together. I advanced from being a financial manager to production director. I learned so much from him.”

By the late 1990s, Durban moved on to a larger record label, Defected. “It had a brilliant team putting out hit records, getting to the top of the chart. I thought I’d ‘hit the jackpot’, but then I learned the label was owned by Ministry of Sound, which Defected owed a lot of money. It became a nightmare, but that was part of my life’s incredible journey.”

Realizing he didn’t want to stay there either, Durban decided to start his own company. “It was in 2003. I was married with two daughters. I knew it was a risk, but I wanted freedom, to choose my own clients, to control my life. It’s the kind of decision that separates two kinds of people,” he said. “You either stay in a place that’s not good for you and live as a salaried slave your whole life, or you are courageous enough to take a chance, while having faith in yourself. I knew I was able to do it because I’ve learned a lot from Harris’s entrepreneurial spirit. I realized that the path to profit was to be my own boss. I needed to control my time. I saw I was highly efficient at what I did, and I succeeded.”

Now living in Israel, Durban is excited to talk about curating a new exhibition titled “07SH10AH23”, which focuses on the trauma of the October 7 massacre, which opened on Holocaust Remembrance Day. “It features over 20 Israeli artists, including hostage survivor Moran Stella Yanai, who is reconstructing her Nova music festival jewelry stand,” he said.

“I couldn’t help but see, in my mind, a parallel between the genocide carried out by the Nazis and what happened in Israel on October 7. Although the scale of the horror is different, the intent was the same.

I wanted to dig into that, to speak with Israeli artists and examine their work before and after the October 7 massacre. Some pieces predate the atrocities but now seem chillingly prophetic.”

“The exhibition is a result of those conversations and my clear understanding that every Israeli’s soul was changed since that day. The pain runs deep, affects every aspect of life, and shapes the art being created now. But the exhibition also testifies to the strength and resilience of this magnificent country.”

Where were you on October 7?

“I had just started a retreat on October 6. I was completely disconnected for a week, with no access to the phone or the news. Only on the 13th did the retreat director tell me that Hamas had invaded Israel. It took me hours to understand what had happened and put the pieces together. Once I did, I felt immense sorrow and horror. I realized this abominable attack was catastrophic for Israel.

I read about the Holocaust as a child, about what the Jews went through back then. Learning that Israelis had been slaughtered in their homes, in their beds, that was a new level of fear for me. I knew Israel would never be the same as they were before the slaughter.

I felt the need to help somehow, to be useful. It was a moment when I felt that being Jewish, together with being Israeli, was not the same as being only Jewish. My bond with Israel deepened. I joined pro-Israel rallies. Later, I came here, and this exhibition is another part of that feeling.”

Have you witnessed or personally experienced antisemitism?

“Absolutely. Not directed at me personally, but the day after the October 7 massacre, there were pro-Palestinian rallies in London. It showed me how little it takes for much of the world to turn antisemitic.”

How did the idea of the exhibition spark?

“On one of my visits to Israel after October 7, I was introduced to the director of a steel plant in south Tel Aviv. He had been showcasing his own artwork on the building’s second floor. He asked my advice as to how to put the showcase on Tel Aviv’s art map.”

“That led me to the idea of creating an exhibition commemorating October 7, using it with the help of Israeli artists to tell the story of how the country changed after the massacre. I began connecting with Israeli artists on Instagram, flying back and forth to visit their studios in Israel. In the end, everyone embraced the project wholeheartedly. They understood its purpose. This isn’t a photomontage of October 7, but rather an exploration of the change that followed it. It’s about how the artists painted before October 7 and how they paint now. Art is a mirror that reflects emotions.”

5 View gallery

Durban next to work of Matan Sacofsky, presented in the exhibition “07SH10AH23”

(Photo: Pini Siluk)

What do you hope will happen following the exhibition?

“Beyond Israelis visiting it, I want to take it abroad. There’s so much talent here that the world doesn’t recognize. I’d like to use this exhibition to raise awareness of what happened in Israel, and to elevate Israeli artists internationally. To show the world how much creativity exists here, despite the hardship. It’s a kind of cultural advocacy. Not enough Israeli art reaches international collections, and that needs to change.”

What’s next for you?

“Right now, I’m a curator. This exhibition is a full-time project. I also manage several private collections in the UK and continue collecting myself. I want to keep curating, see where it leads me, and explore things others might shy away from.

One key thing I learned from Banksy is that controversy works. That’s why I want to keep working as a curator of significant, provocative exhibitions. I believe art can tell powerful stories and also bring comfort to both creators and viewers. It can be hard to tell a certain story that some people won’t want to hear, but that won’t stop me.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.