Hip-Hop was created in the early 1970s, in South Bronx, a predominantly Black, economically depressed section of New York City. The history of Hip-Hop is complex. Its origin is often shrouded in a mystery of who was the first to do it.

According to The Kennedy Center, it was created by DJ Kool Herc, who in August of 1973, spun two of the same record in twin turntables, switching between them to isolate and extend percussion breaks, therefore extending what was considered the most danceable part of the song.

Collectively, DJ Kool Herc (Clive Campbell), Afrika Bambaataa and Grandmaster Flash are often considered the “holy trinity of early Hip-Hop.”

Now, 50 years later, the once-underground scene has become a mainstream cultural touchpoint. It’s more than a genre of music – it’s a living, breathing pursuit and a culture of its very own. That’s the case whether it’s on the streets in its native New York or brought to life by creatives in a Fort Wayne venue.

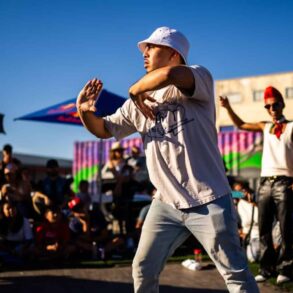

Jamaris Tubbs, who goes by the name J. Tubbs.Hip-Hop scholars have four foundational elements that characterize Hip-Hop culture– DJing, MCing/rapping, breaking, and writing.

Jamaris Tubbs, who goes by the name J. Tubbs.Hip-Hop scholars have four foundational elements that characterize Hip-Hop culture– DJing, MCing/rapping, breaking, and writing.

DJing is defined as the artistic handling of beats and music.MCing/rapping is putting spoken word poetry to a beat. Breaking or b-boying/b-girling is Hip-Hop’s dance form and writing is a highly stylized form of graffiti with paint.

These forms of expression have also developed into further subcultures that have attracted artists of all stripes, creating a multibillion-dollar industry.

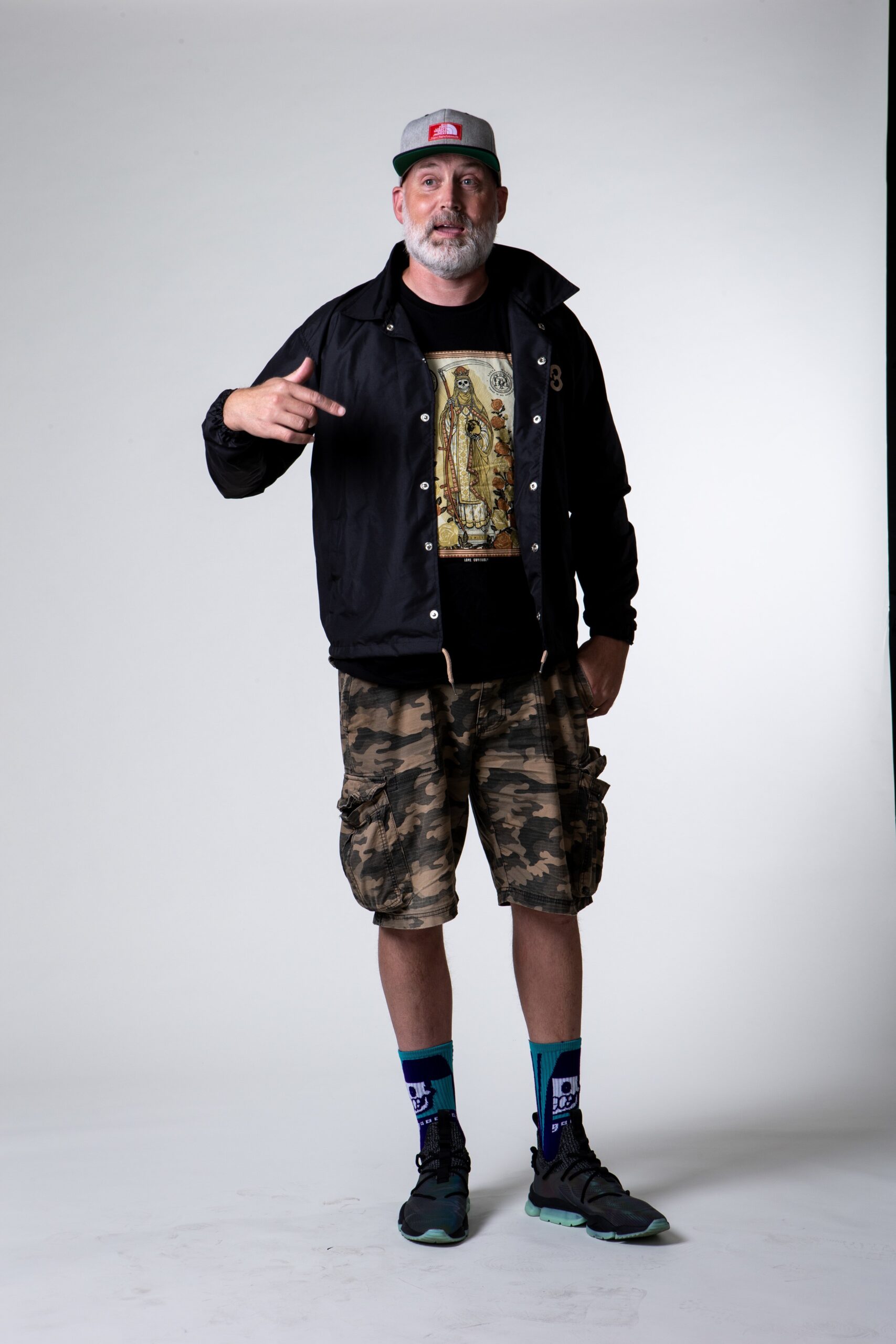

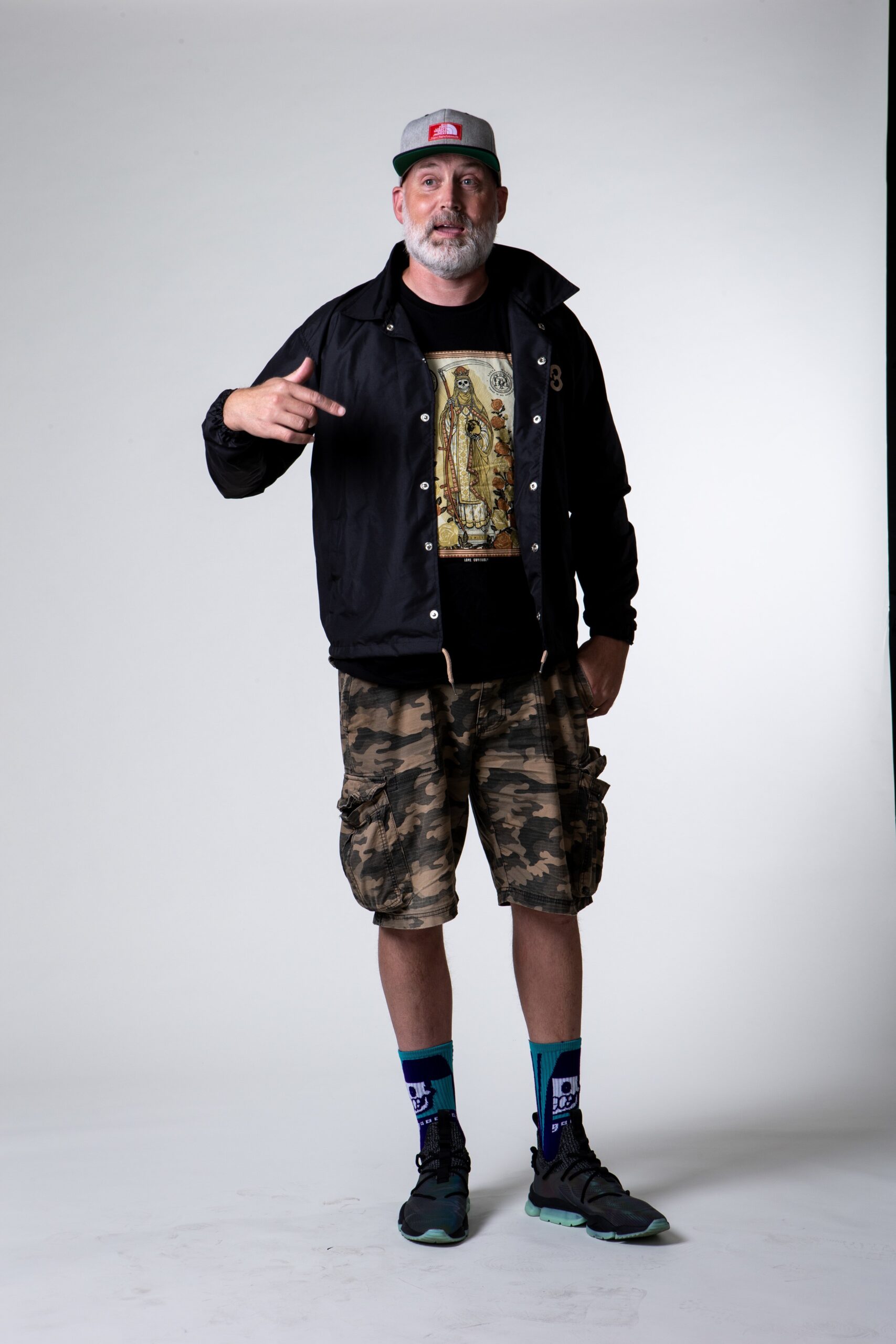

Like other American cities, Fort Wayne has several players who’ve fostered the scene and continue to carry the symbolic torch. Jamaris Tubbs, who goes by the name J. Tubbs, is among those who have elevated Hip-Hop’s profile in Fort Wayne.

The virtuoso says his upbringing was fertile ground for his artistic pursuits.

“My mom pretty much introduced me to Hip-Hop,” he says, reflecting on his seminal influences. “She’s a big Tupac and OutKast fan. My love for Hip-Hop just pretty much started from there.”

Graffiti art from artist Cost Artworks at The Turtle Run Wall off of 4th Street, near Lawton Skate Park.His start in Hip-Hop began with pursuing writing lyrics and songs, but that didn’t stick. When he got to college at Indiana Tech, Tubbs says that was when he explored Hip-Hop more seriously. His friends, recognizing his talent, encouraged him to rap at talent shows. He did and eventually, he met some people from Sweetwater Sound who got him into recording music.

Graffiti art from artist Cost Artworks at The Turtle Run Wall off of 4th Street, near Lawton Skate Park.His start in Hip-Hop began with pursuing writing lyrics and songs, but that didn’t stick. When he got to college at Indiana Tech, Tubbs says that was when he explored Hip-Hop more seriously. His friends, recognizing his talent, encouraged him to rap at talent shows. He did and eventually, he met some people from Sweetwater Sound who got him into recording music.

“The DJ side of things started in college as well, because we had parties and stuff like that,” he says. “Everybody knew I knew how to rap, so they just assumed I knew how to DJ, which are two completely different things.”

Tubbs — a creative chameleon — embarked on a self-taught journey to DJing, making a name for himself in the process. More than 15 years later, he’s established himself while being an advocate of rooting and growing creativity in Fort Wayne. Today, he spends his time as an artist, producer and President/CEO of the Hip-Hop Convention Fort Wayne.

J. TubbsTubbs cites one milestone in particular that has helped put Fort Wayne on the regional and national stage culturally nearly a decade ago.

J. TubbsTubbs cites one milestone in particular that has helped put Fort Wayne on the regional and national stage culturally nearly a decade ago.

“Nyzzy Nyce is the biggest Hip-Hop artist who came from here,” he says. “He’s residing in LA now. Long story short, Nyzzy spearheaded the 2014 My City project that helped put the city in a position in which people were paying attention to Hip-Hop a little bit more. (They realized) there’s a lot of good local talent and people putting in the hard work to make things happen. So I like to think that’s really when it kind of took off.”

Fast forward to the present day, Tubbs says that the culture is still robust but there’s always work to be done to help sustain it. That’s one of the reasons he started the Fort Wayne Hip-Hop Convention. He says there’s a place for DJing and MCing, but simultaneously, there’s a need to introduce the city to the other elements of Hip-Hop culture. And that’s the void filled by the Fort Wayne Hip-Hop Convention, in his estimation.

Tubbs says the annual event, held at various venues in Downtown Fort Wayne, brings different crosssections of the Hip-Hop community under one roof. Artists and fans were able to collaborate and weigh in on the past, present and future of the movement.

When it comes to the future, Tubbs says he feels like his efforts are bearing fruit. The self-described “big brother” of the Fort Wayne Hip-Hop scene says the city’s artistic diversity is a hidden gem. Fort Wayne has the same caliber of talent as in big cities, but that talent might be more under the radar compared to larger markets.

“I feel like it’s to the point where we will become a staple for talent,” Tubbs says. “While Indianapolis, Chicago, Detroit, etc. have always been hubs for entertainment and music, Fort Wayne has been quietly coming up.”

Hip-hop dancer Jocelyn “Evil Lynn” EckhoutJocelyn “Evil-Lynn” Eckhout has seen the Hip-Hop scene evolve and change over the years. A B-girl, or breakdancer, she first moved to Fort Wayne in the early 2000s. Coming from South Florida’s breakdancing community, she was anxious to find her niche here, but she took it upon herself to create and distribute flyers to find other people already invested in the Hip-Hop scene.

Hip-hop dancer Jocelyn “Evil Lynn” EckhoutJocelyn “Evil-Lynn” Eckhout has seen the Hip-Hop scene evolve and change over the years. A B-girl, or breakdancer, she first moved to Fort Wayne in the early 2000s. Coming from South Florida’s breakdancing community, she was anxious to find her niche here, but she took it upon herself to create and distribute flyers to find other people already invested in the Hip-Hop scene.

Eckhout says she was overwhelmed by the interest from dancers already steeped in the breaking culture.

“(The B-boy cohort) all showed up to check out who I was and why I was saying, ‘Hey, let’s have a B-boy practice,’” she says. “They were really checking out people because they wanted to vet them and their reputation. I was so new to it that I had no idea that people would show up.”

It was then that Eckhout met Joshua Rowlett, who went by the alias “Coda.” He influenced her and her art, as did countless other “heads” in the scene.

“Coda, along with his then-wife Amber, brought Hip-Hop to life,” she says. “ I would have never known what Hip-Hop culture really is (without them). It’s much more than music. It’s much more than DJing. It’s the art, the music, the dance — all in one.”

Speaking of dance, volunteering at a dance studio has also expanded her creative horizons. In hindsight, Eckhout says it was important to keep her dancing separate from her livelihood.

“I just volunteered,” she says. “I didn’t want any money. I just wanted to be a part of the culture and help teach students breaking and other street-style dance forms, so that’s pretty much where I developed as a performer.”

Hip-hop dancer Jocelyn “Evil Lynn” EckhoutJust as important as the mechanics of dance are unspoken rules, she says as a white woman, she does her best to be conscientious of Hip-Hop’s origins.

Hip-hop dancer Jocelyn “Evil Lynn” EckhoutJust as important as the mechanics of dance are unspoken rules, she says as a white woman, she does her best to be conscientious of Hip-Hop’s origins.

“I keep that in mind, and I don’t take it lightly,” she says. “At the same time, I don’t feel pressure from it, because I always have people that I can talk to and understand their perspectives. At the end of the day, as far as the dance portion of it, (it calls for being socially aware) and also understanding etiquette. I think that goes a long way.”

Hip-Hop’s longevity and relevance in Fort Wayne and beyond also depend on intentionality. With this in mind, she says it’s important for parents to get involved. That means bringing their children to events and taking the time to understand Hip-Hop in all forms and offer context. The goal is that the next generation is educated so they can become cultural ambassadors.

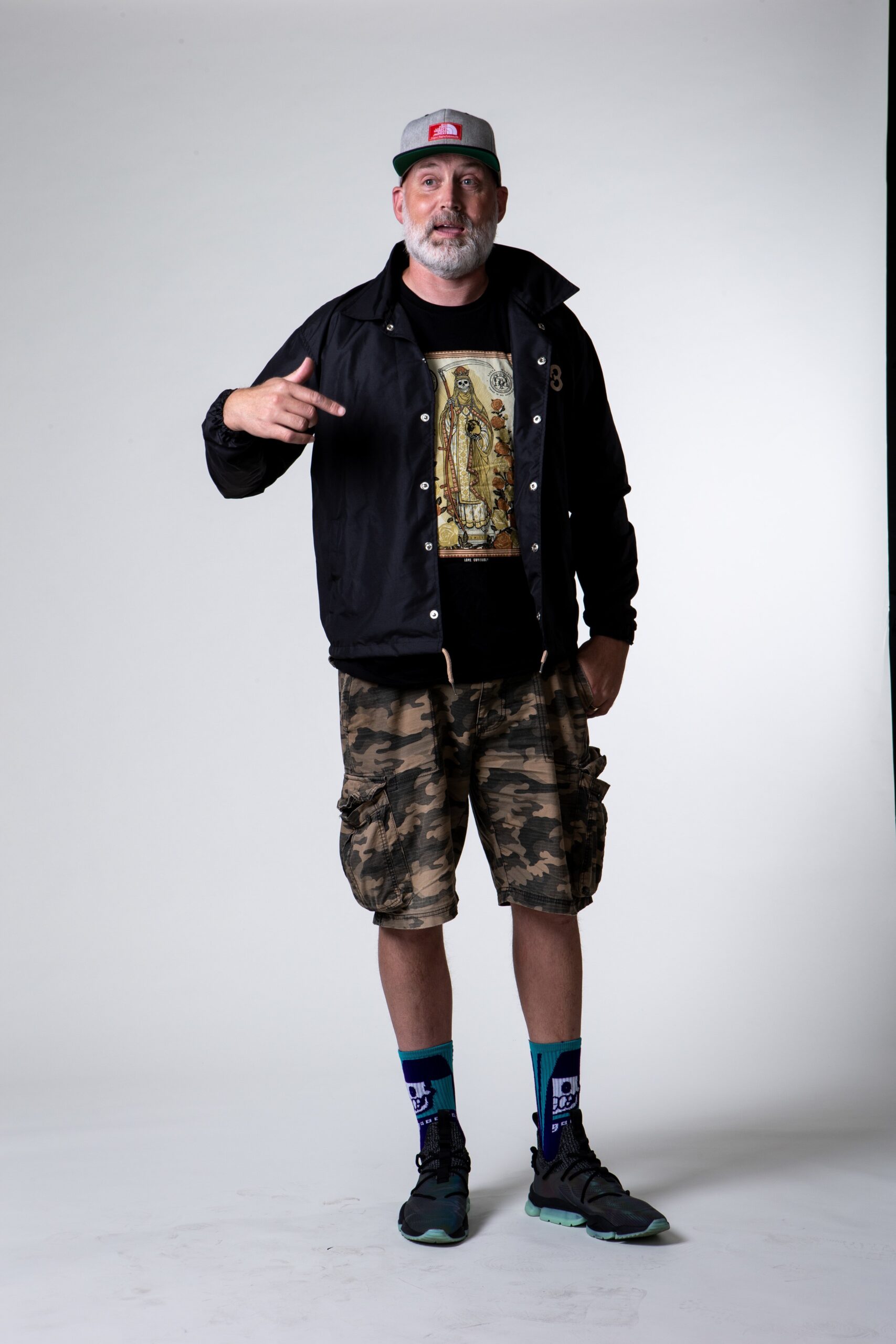

SankofaStephen Eric Bryden— known to fans as Sankofa — agrees. However, he’s also concerned about the here and now, practically speaking. He says venues like the Brass Rail give artists from a wide variety of genres a platform and audience. In his estimation though, the venue has only scratched the surface of giving emerging artists a literal outlet.

SankofaStephen Eric Bryden— known to fans as Sankofa — agrees. However, he’s also concerned about the here and now, practically speaking. He says venues like the Brass Rail give artists from a wide variety of genres a platform and audience. In his estimation though, the venue has only scratched the surface of giving emerging artists a literal outlet.

“There’s only one Brass Rail,” he says. “It seems that with this emphasis on the arts, with murals and all that other stuff, there’d also be an emphasis on performance venues for local musicians. The talent in this city, regardless of where you may choose to look, is world-class.”

To that end, Bryden says he has immense respect for people like J. Tubbs and Francisco “Paco” Reyes, whose grassroots work is advancing the city’s creative class. Reyes’ project, Fort Wayne Open Walls, has brought together community members and national artists. In his opinion, these are the types of people and projects that will take Fort Wayne to the next level.

“They’re community-minded individuals who are seeking to build a stronger community,” he says. “In making those connections, it’s my hope that those people continue upon that path and continue to build with a wide variety of people.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.