A silent transformation has been underway in a city once drenched in the echoes of rebellion. The raw, defiant graffiti—etched hurriedly during the struggle to dismantle a fascist regime—has begun to fade, not under time pressure but through the careful strokes of “beautification.” What do you think? If history had a colour, would it be pastel?!

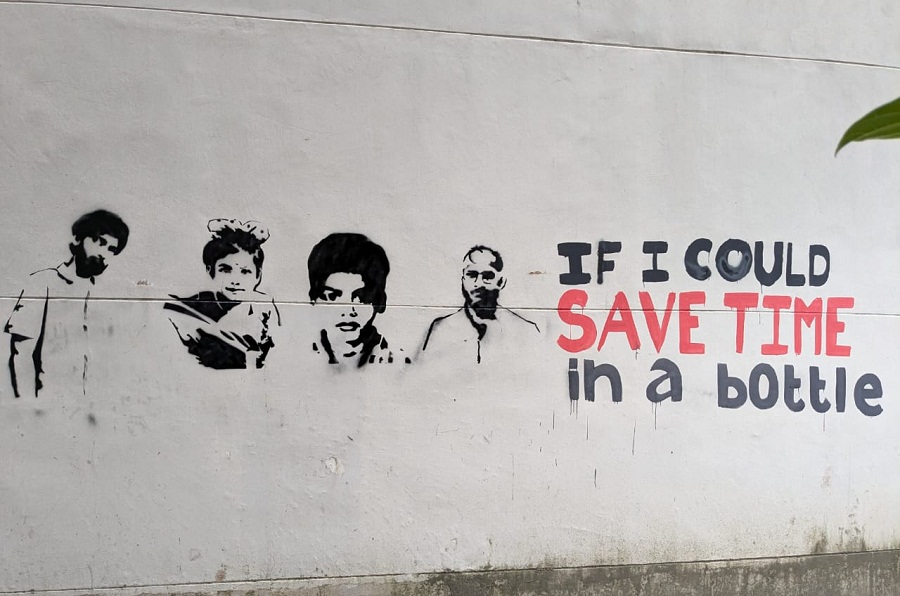

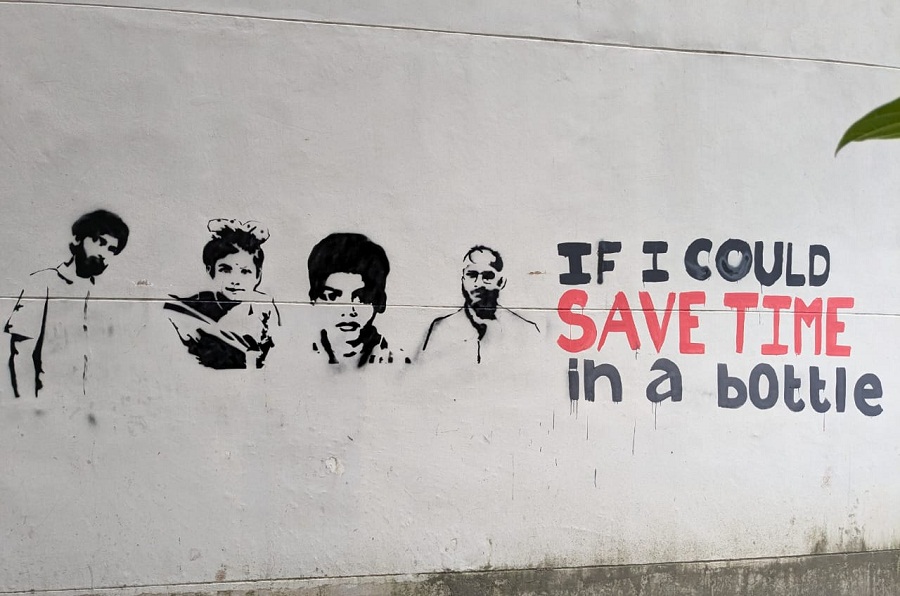

Graffiti has always been seen as vandalism—at least by those in positions of authority. However, graffiti is far more than mere defacement; it is a language of protest that those in power often find unpalatable. Graffiti artists do not ask for permission or concern themselves with consequences. The marks they leave behind usually go unnoticed until long after creation.

Take Banksy, a world-renowned graffiti artist whose identity is still a mystery. In a similar tone, the artist behind the famous “Subodh” series, known as “Hobe Ki,” also remains unknown in Bangladesh.

One notable local artist is BijoyGraph, whose striking graffiti has been wiped away numerous times, yet he continues to return and create anew.

Following a hard-fought revolution in July, many citizens aimed to preserve the memories of the bloodshed and resilience. The walls transformed into a testament of pain and protest, adorned with urgent warnings, poignant reminders, and the names of those lost. These were not just random marks—they were calls for justice, unfiltered accounts of suffering, and, above all, evidence of what was endured.

But these memories are now being replaced by glossy murals. These sanitized artworks, led by well-meaning civilized society under the banner of beautification, celebrate unity and hope while erasing the grit that defined the original graffiti.

The scars of gunshots and the shaking hands that once held spray cans are covered with vibrant colours and happy figures. As the city’s walls transform, a poignant debate rages on. Are we preserving history or painting over it?

There is a particular artistic value in raw, risky graffiti—like spray-painted work on a police box or a metro rail pillar—that surpasses even the coordinated efforts of organized groups, regardless of how revolutionary their message might appear.

The establishment will permanently erase graffiti, just as they erase voices of dissent. But mural art, created in collaboration with those in power, lacks the raw defiance of graffiti.

It ceases to be graffiti and becomes something else entirely. These sanitized versions dilute the sacrifices and make our history palatable.

Graffiti has played a crucial role in the revolutionary movements of these locales. Still, as the conflict subsides, a new graffiti and street art scene emerges—often one that ushers in postconflict consumerism, gentrification and anaesthetized forgetting. Graffiti can be erased and its artists silenced, but the rebellious spirit it embodies can never be destroyed.

For those who stood on the frontlines, the original graffiti was a daily reminder of lives lost and battles fought. The question now arises: Does beautification honour the memory of the revolution, or does it sanitize history for the comfort of the present?

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.