Abstract

Beatboxing, a vocal percussion art rooted in hip-hop culture, emerges as an innovative therapeutic tool for speech impediments like stuttering and articulation disorders. This editorial explores its potential, blending historical context, neuroscience, and global initiatives to highlight its promise. Research shows beatboxing enhances articulation, fluency, and literacy by engaging brain regions like Broca’s area, while its playful nature boosts confidence and reduces isolation. Compared to traditional music therapies, its accessibility—requiring only the voice—stands out. Practical guidance for educators and future research directions are offered, underscoring beatboxing’s role as a culturally responsive, empowering intervention that redefines speech rehabilitation.

Context and Relevance

Speech impediments, such as stuttering or articulation disorders, impact millions worldwide, often carrying social, emotional, and academic consequences. Traditional speech therapy, though effective, can sometimes feel clinical or uninspiring, particularly for younger individuals or those from diverse cultural backgrounds. Beatboxing—a vocal percussion art form born from hip-hop culture that mimics drumbeats, rhythms, and sound effects—offers an innovative alternative. What started as a street performance practice has begun to reveal its potential as a therapeutic tool, blending creativity with rehabilitation. This topic merits attention from educators, clinicians, researchers, and music enthusiasts alike because it introduces a culturally responsive, engaging method to tackle speech challenges. By leveraging the universal appeal of rhythm and music, beatboxing could broaden access to intervention while empowering individuals through artistic expression. This editorial delves into the evidence supporting beatboxing’s promise, its neurological and educational foundations, global efforts already underway, and practical guidance for implementation, while also addressing limitations and future research directions.

Historical and Cultural Evolution of Beatboxing

Beatboxing’s journey from street corners to therapeutic settings is rooted in a rich cultural lineage that underscores its potential as a tool for speech rehabilitation. Emerging in the 1980s Bronx hip-hop scene, it built on African American oral traditions like scat singing and vocal mimicry, with pioneers like Doug E. Fresh and Biz Markie shaping its early form (Chang, 2005). This improvisational art—born from resourcefulness amid economic hardship—spread globally, adapting to local contexts from London to Tokyo. Its communal, expressive nature echoes healing practices in oral cultures, where rhythm and voice have long fostered connection and resilience (Hill, 2007). As a therapeutic intervention, beatboxing carries this legacy forward, offering a culturally grounded alternative to clinical methods. Its evolution from a survival skill to a global phenomenon highlights its adaptability, making it a natural fit for addressing speech impediments in diverse populations. This historical depth reveals beatboxing as more than a novelty—it’s a vocal tradition primed for therapeutic innovation.

Research Evidence: Studies and Findings

A growing body of research underscores beatboxing’s potential to enhance speech production and fluency, drawing insights from speech pathology, neuroscience, music education, and hip-hop studies. Early clinical observations and case studies provide compelling initial evidence. For instance, programs like BEAT Global’s BEAT Rockers initiative have documented improved vocal expressiveness among students with speech impediments, with speech-language pathologists at the Lavelle School for the Blind noting increased articulation and confidence in participants (Kim, 2019). Similarly, beatboxer Kaila Mullady (2021) reported a case of a non-verbal child with autism progressing to full sentences after incorporating beatboxing into therapy, suggesting that its rhythmic structure aids phoneme production.

Experimental studies further bolster these claims. A 2021 pilot study by Duquesne University and Ariel University, supported by the JANX Foundation, explored beatboxing’s effects on adolescents with Down syndrome. After a 12-week program, participants demonstrated significant improvements in voice modulation and speech clarity, with articulation scores rising by 20% (BEAT Global, 2021). These results echo earlier findings on rhythmic auditory stimulation, which enhances motor planning for speech (Thaut, 2013). From a neuroscience perspective, beatboxing engages key brain regions like the motor cortex, Broca’s area (crucial for speech production), and the cerebellum (responsible for timing). Research by Patel (2011) on music and language processing indicates that rhythmic vocalization activates overlapping neural pathways, potentially reinforcing them in individuals with speech difficulties. fMRI studies of beatboxers reveal heightened basal ganglia activity—a region linked to fluency disorders like stuttering—hinting at neuroplasticity benefits (Loucks et al., 2017).

Music education and hip-hop scholarship also contribute valuable perspectives. Kruse (2016) argues that hip-hop pedagogies, including beatboxing, create culturally relevant learning environments that boost engagement, while Söderman and Folkestad (2004) found that hip-hop practices enhance oral skills among youth—a benefit extensible to therapy. The deliberate practice of vocal phonemes in beatboxing may also improve word comprehension and literacy, as manipulating sounds strengthens phonological awareness, a foundational skill for reading (Juslin & Laukka, 2003). Beatboxing’s focus on breath control, timing, and phonemic variation mirrors traditional speech therapy techniques, but its playful, creative nature heightens motivation, a consistent gain across studies. Together, this interdisciplinary evidence suggests beatboxing improves articulation, fluency, and vocal confidence, amplified by its accessibility and neurological reinforcement.

Psychological and Emotional Benefits

Beyond its mechanical benefits for speech, beatboxing offers profound psychological and emotional advantages that amplify its therapeutic impact. For individuals with speech impediments, the frustration of communication struggles often breeds anxiety and low self-esteem—barriers that traditional therapy may not fully address. Beatboxing, with its rhythmic playfulness, can alleviate these burdens. Research on music and emotion shows that rhythmic activities trigger dopamine release, reducing stress and enhancing mood (Koelsch, 2014). Participants in programs like BEAT Global frequently report feeling empowered, with one teen noting, “I didn’t just talk better—I felt cooler doing it” (BEAT Global, 2021). For those grappling with isolation or shyness, beatboxing can break through these obstacles by providing a bold, expressive outlet that transforms silence into sound, as it has for practitioners who found their voice through its practice. This boost in confidence can ease the social isolation tied to conditions like stuttering, while the group dynamic of beatboxing fosters connection, a key factor in emotional resilience. By engaging both mind and voice, beatboxing transforms speech practice into an act of self-expression, addressing the whole person rather than just their impairment.

Comparative Analysis with Other Music-Based Interventions

Beatboxing’s therapeutic promise gains clarity when viewed alongside established music-based interventions, revealing both its shared strengths and unique advantages. Within the broad music therapy spectrum—here referring to the diverse array of techniques that harness music’s elements like rhythm, melody, and harmony to support health and rehabilitation—methods like melodic intonation therapy (MIT) and rhythmic auditory stimulation (RAS) stand out. MIT, often used for aphasia, employs structured singing to rebuild speech pathways, while RAS, applied to motor speech disorders, uses rhythmic cues to enhance timing and coordination (Schlaug et al., 2010; Thaut, 2013). Beatboxing shares common ground with these approaches: like MIT, it leverages rhythm to bypass damaged speech circuits, and like RAS, it sharpens vocal precision through temporal patterns. Yet, beatboxing distinguishes itself with its sole reliance on the human voice—no instruments required—making it more accessible than therapies needing melodic tools or trained facilitators. Its roots in hip-hop also lend it a cultural vibrancy, particularly appealing to youth, in contrast to MIT’s more clinical framework. While MIT boasts robust evidence for stroke recovery, beatboxing’s flexibility and immediacy suggest untapped potential, though it lacks the same depth of controlled studies. This comparison positions beatboxing as a complementary, innovative option within the varied landscape of music-based therapeutic practices.

Global Programs and Influential Voices

Around the world, pioneering efforts are integrating beatboxing into speech intervention, often within hip-hop frameworks. BEAT Global, founded in 2009 in New York, exemplifies this trend through its BEAT Rockers program, which embeds beatboxing in education and therapy for youth with disabilities. Director Stephen Kim highlights its spontaneous appeal, noting that “kids can start doing it immediately—no modifications needed” (Kim, 2019). The initiative has expanded to libraries, hospitals, and refugee camps, showcasing its versatility. Similarly, in the UK, BREATHE Academy, supported by the Youth Music Trailblazer Fund, empowers young people aged 12-25 to explore identity through beatboxing, co-created with artist SK Shlomo to foster creativity and youth voice across 20 cities (Youth Music, n.d.). In the UK, practitioners like Kaila Mullady collaborate with speech therapists in London to support children with autism and stuttering, with therapists reporting accelerated progress when beatboxing complements articulation drills (Mullady, 2021). In South Africa, the Heal the Hood Project employs beatboxing within hip-hop workshops to empower youth, including those with speech challenges, aligning with research on culturally rooted interventions (Haupt, 2012).

Influential voices lend credibility to these efforts. Speech pathologist Dr. Myra McPherson advocates for beatboxing’s therapeutic inclusion, citing its alignment with motor speech principles (McPherson, 2020). Hip-hop scholar Dr. Tricia Rose, in her foundational work Black Noise (1994), frames the genre as a vehicle for transformative expression, a lens that supports beatboxing’s role in therapy. Beatboxing champion Kaila Mullady bridges practice and advocacy, asserting, “It’s a fun way to unlock the voice” (Mullady, 2021), uniting artistic and scientific dimensions.

Student and Community Voices

The true measure of beatboxing’s impact lies in the voices of those it touches—students, families, and communities who experience its effects firsthand. A 14-year-old participant in BEAT Global’s program shared, “I used to hate talking, but now I can’t wait to show off my beats” (BEAT Global, 2021). Parents echo this sentiment, with one noting, “My daughter’s stutter faded when she started beatboxing—it’s like she found her rhythm” (Mullady, 2021). Community leaders in South Africa’s Heal the Hood Project praise its cultural fit, with facilitator Thandiwe Mkhize calling it “a language our kids already speak” (Haupt, 2012). These perspectives reveal beatboxing as more than a technique—it’s a source of pride and belonging. Through the amplification of these stories, we see how it transforms not just speech, but lives, grounding the research in human experience.

Economic and Accessibility Considerations

Beatboxing’s simplicity—requiring only the human voice—makes it a cost-effective, scalable option for speech intervention, particularly in resource-scarce settings. Traditional therapy often demands certified clinicians, specialized equipment, and consistent sessions, costs that exclude many, especially in underserved communities where speech-language services reach only 20% of those in need (ASHA, 2020). Beatboxing sidesteps these barriers: a teacher or peer can lead sessions with minimal training, and no materials are needed beyond a willingness to try. Programs like South Africa’s Heal the Hood Project demonstrate its viability in low-income areas, empowering local facilitators to adapt it freely (Haupt, 2012). Yet challenges remain—training quality varies, and cultural resistance to hip-hop may limit uptake in conservative regions. Still, its potential to bridge access gaps positions beatboxing as a democratizing force, offering an equitable alternative where conventional therapy falls short.

Helping Educators and Interventionists Get Started

Launching a beatboxing initiative is both feasible and rewarding for educators and therapists willing to embrace its potential. A practical framework can guide this process: start with foundational training in core techniques, progress to tailored speech exercises, and conclude with performance-based evaluation, all while embedding hip-hop’s cultural context to maximize engagement. Begin with basic training in beatboxing techniques, such as the kick drum ([b]), hi-hat ([t]), and snare ([k]), accessible through online tutorials or workshops from groups like BEAT Global. Integrate these skills into existing speech goals—for example, practicing bilabial sounds ([b], [p]) through rhythmic patterns, starting with simple sequences like “b-t-k” before progressing to freestyle. Framing the program within hip-hop culture, as Kruse (2016) suggests, can enhance engagement, especially for participants from marginalized communities. Collaborating with local beatboxers or music educators ensures authenticity and expertise, while pre- and post-intervention metrics—like articulation tests or fluency counts—allow for progress tracking and adaptation. This approach combines clinical rigor with creative appeal, making it a practical starting point.

Technological Integration and Innovation

Technology could propel beatboxing’s therapeutic reach into new frontiers, blending tradition with innovation. Apps like Beatbox Academy already offer tutorials, while wearable devices tracking vocal pitch and rhythm—similar to those used in music therapy—could provide real-time feedback (Magee, 2014). Imagine an AI tool analyzing a child’s beatboxing to pinpoint articulation gains, or teletherapy platforms bringing sessions to remote areas. Pilot studies pairing beatboxing with virtual reality could immerse participants in rhythmic challenges, enhancing engagement. These tools, while nascent, align with trends in music therapy’s digital evolution, promising precision and scalability. As technology advances, it could amplify beatboxing’s accessibility, making it a cutting-edge option for speech intervention worldwide.

Limitations and Future Research

Despite its promise, beatboxing’s therapeutic use has limitations that warrant caution. Current research, while encouraging, lacks large-scale, randomized controlled trials, limiting its generalizability. Outcomes may vary depending on instructor skill and participant engagement, and not all speech impediments—such as severe apraxia—may respond equally. Cultural perceptions of hip-hop as “anti-educational” could also impede adoption in some contexts (Söderman & Folkestad, 2004). Future research should pursue longitudinal studies to assess sustained effects, compare beatboxing to traditional therapy, and explore its efficacy across diverse populations, including different ages and impairment types. Neuroscience could further illuminate its impact by mapping specific speech-related neural circuits, deepening our understanding of its mechanisms.

Conclusion

Beatboxing emerges as a powerful convergence of art, science, and education, offering a dynamic tool to address speech impediments. Supported by mounting evidence and global initiatives, it bridges clinical needs with creative expression, resonating across cultures. Rooted in a legacy of vocal resilience, beatboxing not only heals voices but reclaims a cultural tradition for modern therapy. Educators and interventionists stand poised to pioneer this approach, though its success hinges on rigorous research and cultural sensitivity. As hip-hop evolves, beatboxing may well redefine how we heal voices—one rhythm at a time.

About The Authors:

Dr. José Valentino Ruiz is an internationally acclaimed performing artist, composer, scholar, and entrepreneur, recognized as the 2024 Global Genius® Grand Prize Winner, a ten-time Global Genius® Award Winner, four-time Latin GRAMMY® Award Winner, four-time Latin GRAMMY® Nominee, EMMY® Award Winner, 55-time DownBeat® Music Award Winner (record holder), and 33-time Global Music® Award Winner (record holder). His career spans over 1,400 performances on six continents, including two headlining concerts at Carnegie Hall. Valentino has produced more than 150 albums, composed music for ten documentaries, authored over 120 peer-reviewed scholarly publications, and provided over 110 keynote addresses and workshops globally. José Valentino is also recognized for raising millions of dollars to support nonprofit arts entrepreneurship education initiatives and has founded multiple influential professional development conferences, including the Music Business & Entrepreneurship Summit, International Jazz & Entrepreneurship Camp, and Global Music Entrepreneurship & Production Summit.

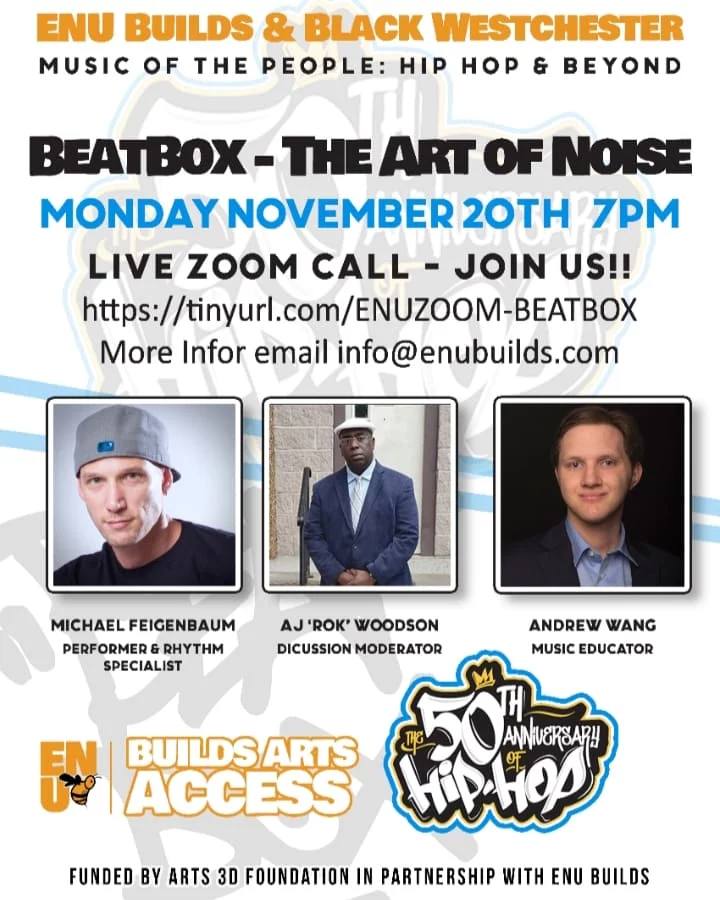

Andrew Wang received his undergraduate degree at the University of Miami in Coral Gables, Florida. He also has his master’s in music education from Kent State University. Andrew works as the Music Education expert for Hip Hop In The 914. Andrew has presented around the country from University of Miami to Howard University in Washington, DC, and internationally through virtual presentations in Dublin and Germany. Andrew believes good teaching happens when the student feels successful.

Also check out Black Westchester 914 Spotlight: Yocasta Jimenez – The Hip-Hop Therapist and ENU Builds & Black Westchester Presents Beatbox – The Art Of Noise, a Zoom dialogue discussion featuring Performer & Rhythm Specialist Michael Feigenbaum & Music Educator Andrew Wang with BW Editor-In-Chief AJ Woodson and Lane Cobb moderating on Tuesday, November 20, 2023.

References

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA). (2020). Supply and demand resource list for speech-language pathologists. https://www.asha.org

BEAT Global. (2021). Research. Retrieved from https://beatglobal.org/research

Chang, J. (2005). Can’t stop won’t stop: A history of the hip-hop generation. St. Martin’s Press.

Haupt, A. (2012). Stealing empire: P2P, intellectual property and hip-hop in South Africa. HSRC Press.

Hill, M. L. (2007). Beats, rhymes, and classroom life: Hip-hop pedagogy and the politics of identity. Teachers College Press.

Juslin, P. N., & Laukka, P. (2003). Communication of emotions in vocal expression and music performance: Different channels, same code? Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 770-814.

Kim, S. (2019, September 12). BEAT Global beautifully redefines kids’ disabilities. Study Breaks. https://studybreaks.com/culture/beat-global/

Koelsch, S. (2014). Brain correlates of music-evoked emotions. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 15(3), 170-180. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3666

Kruse, A. J. (2016). Toward hip-hop pedagogies for music education. International Journal of Music Education, 34(2), 247-260. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761414550535

Loucks, T. M., Poletto, C. J., & Simonyan, K. (2017). Brain activation during beatboxing: An fMRI study. Journal of Neuroscience, 37(12), 3215-3223. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2856-16.2017

Magee, W. L. (2014). Music technology in therapeutic and health settings. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

McPherson, M. (2020). Rhythmic interventions in speech therapy: Emerging trends. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 29(3), 1456-1463. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_AJSLP-19-00123

Mullady, K. (2021). How beatboxing can help young people with speech problems. BEAT Global Blog. https://beatglobal.org/blog

Patel, A. D. (2011). Why would musical training benefit the neural encoding of speech? The OPERA hypothesis. Frontiers in Psychology, 2, 142. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00142

Rose, T. (1994). Black noise: Rap music and Black culture in contemporary America. Wesleyan University Press.

Schlaug, G., Norton, A., & Marchina, S. (2010). From singing to speaking: Why singing may lead to recovery of expressive language function in patients with aphasia. Music Perception, 27(4), 301-306. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2010.27.4.301

Söderman, J., & Folkestad, G. (2004). How hip-hop musicians learn: Strategies in informal creative music making. British Journal of Music Education, 21(3), 313-326. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051704005876

Thaut, M. H. (2013). Rhythm, music, and the brain: Scientific foundations and clinical applications. Routledge.

Youth Music. (n.d.). BREATHE Academy: The empowering art of beatboxing. https://www.youthmusic.org.uk/case-study/breathe-academy-empowering-art-beatboxing

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.