On Saturday, Feb. 22, the Black Healing, Joy & Justice Collective and the Center of Racial Justice and Youth Engaged Research hosted the Black Artistic Symposium: Hip-Hop Praxis from the Classes to the World and the Black Artistic Freedom Closing Dinner. The events were the second and third parts of the weekend-long Black Artistic Freedom Conference, following the W.E.B. Du Bois Poetry Slam held on Friday, Feb. 21. It was organized by Imani Wallace, a fourth-year PhD student of social justice education, W.E.B. Du Bois fellow and newly declared Poet-In-Residence of the W.E.B. Du Bois Center.

According to Wallace, there is a strong intersection between spoken word poetry and hip-hop music. “The elements of hip hop … include emceeing, breakdancing, graffiti, DJing and knowledge of self. And spoken word poetry … incorporates two elements of hip-hop, which are emceeing and knowledge of self. And emceeing is literally … speaking, but in a particular way, in a manner that has meter, in a manner that has rhythm, in a manner that is kind of like a part of some sort of larger production of the ways in which you’re saying it in order to be heard,” Wallace said.

She also maintained there were key differences between hip-hop music and spoken word poetry; specifically, the only physical elements of spoken word poetry are oneself and a microphone.

The symposium was titled and themed on the topic of hip-hop music, as well as its sheer cultural impact and potential for healing. The event opened at 10:00 a.m. with a performance by the UMass Gospel Choir, followed by opening remarks by Dr. Keisha Green, co-founder of the University’s Center of Racial Justice and Youth Engaged Research. Afterwards, the event began with the first four of eight concurrent workshops.

“‘We Deserve It All:’ Justice, Healing and Joy in Hip-Hop Music,” was hosted by Dr. Bryant Best, assistant professor of urban education at Morgan State University in Maryland. The workshop began with a Kahoot quiz with a focus on the history of hip-hop music, including the main elements of the genre. Then, Best turned his attention to the genre’s ability to generate social justice and healing, including by allowing participants to discuss how hip-hop music helped them deal with challenges in their lives.

“I was really impressed by the knowledge that the young people had around hip-hop. The history of it, its beginnings in the 1970s, where it was founded, who started it, and how it connected to their lives,” Best said of the workshop, adding that several attendees knew about less recent hip-hop songs that Best listened to when he was younger.

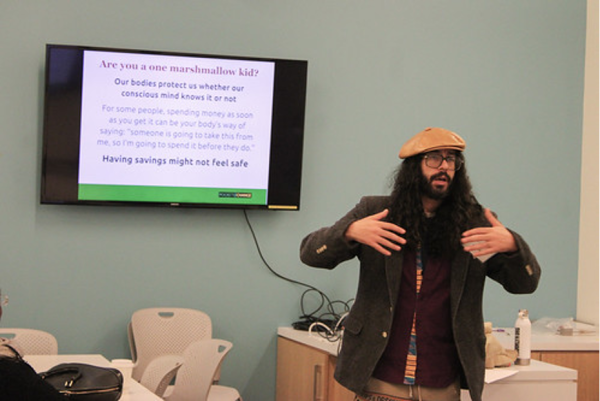

“Hip-Hop as Advocacy for Self and Society” was hosted by Dyalekt, who has worked in education, theater and as an emcee for more than two decades. His workshop was centered around developing a good financial standing in a world centered around money. His focus on hip-hop education is connected to various forms of critical thinking, including “the disciplines that make up social-emotional learning.”

“The big thing that we posit is that systemic oppression messes with your nervous system, and when your nervous system is messed with, you’re not making the financial decisions that lineup with your values,” Dyalekt said, arguing that teaching people about systemic oppression can relieve them of guilt over any financial decisions they might regret.

After the first concurrent sessions ended, the event’s keynote address was delivered by Dr. Lauren Leigh Kelly, associate professor in Rutgers University’s Urban Social Justice Teacher Education Program. Kelly’s address focused on the power of hip-hop music as an integral component of Black culture, and its ability to facilitate discourse on social justice.

“You could have, in one verse, someone talking about violence and murder but then also talking about liberation, and peace and justice … so [hip-hop music] allows for us to sit with the complexities of oppression, of power in society, and also develop strategies for … ‘How do we sort of come to know ourselves in our communities?’ in ways that can support our social action and our pursuit towards liberation,” Kelly said.

In her address, Kelly also played a clip from the song “Freedom,” which was the theme song of the 1995 film “Panther.” She spoke about its indelible cultural impact in the context of Black feminism.

“Every woman in the industry was in that song … why is it that song doesn’t sort of sit in our public consciousness? Why aren’t we thinking about it? Why isn’t it played on the … satellite radio? … Why is it not on people’s playlists? … I would argue that there’s like a deliberate effort to not show us that because it’s an example of something really powerful. It’s an example of women who had power, who had agency,” Kelly said, praising the song for its bold and vivid message that Black women are not simply caretakers, and that they themselves are key combatants in the fight against racism while also forming a strong alliance of their own.

After lunch was provided, the workshops resumed. “Performance Poetry, Slam & Digital Era” was hosted by Roscoe Burnems, a spoken word poet who became Richmond, Va.’s inaugural poet laureate, and who hosted the Poetry Slam the previous night. His workshop was centered around how spoken word poetry and poetry slams continued to serve as a vehicle for social change through storytelling amidst the continued rise of digital technologies.

Burnems praised the Black Artistic Freedom Conference for providing a space where people could work collaboratively towards social change. “I think the takeaway for this is that for this conference is that community is everything. We need each other in order to create change,” Burnems said.

“Articulate Activism: Honoring Black Voices Through Makerspace Creations” was co-presented by Jeremy Reese and Brittany Tate-Reese, both doctoral students in education at Pepperdine University, Calif., who joined the symposium from Chicago, Ill. They focused on ChatGPT as a resource for research, especially with regards to “generating historical context, thematic insights and creative ideas.” Reese and Tate-Reese hoped to impart the importance of research and activism in a modern setting.

“We study activists all the time, but I don’t think we truthfully realize that during that time period, they were just living. And so in this current period of time, if you’re passionate about something, pursue it, because one day someone could be studying you,” Tate-Reese said, adding that she and Reese hope that technology-based activism can also lessen the digital divide.

The symposium ended with closing remarks from Wallace and performances from singer and rapper Brandie Blaze, who generated enthusiasm and camaraderie among the crowd as they joined in with the music.

Then, at 5:00 p.m., the Black Artistic Freedom Closing Dinner commenced at the Bromery Center for the Arts; it was the first time that event was held. Hosted by Burnems, it tied up the excitement of the day and celebrated the success of the conference as a whole. Wallace said the dinner gave people the chance to network with each other outside of the limited timeframe the symposium offered.

“I myself am a professional spoken word artist and I don’t even really get to tell my own story throughout the conference … I just want to make sure that everyone else has the platform to share theirs,” Wallace said. While she utilized the dinner to share more of her work with the audience, she also aimed to further the platforms of her fellow performers to celebrate all that had been achieved during the events and spread further joy among the audience.

At the dinner, good food and fun were had by all attendees. Performances included a set by comedian Trey Mack, who travelled to Amherst from Dallas, Tex., to entertain the audience; Burnems himself performed a series of poems about his life, parenthood, fighting oppression and Black joy. In one of his poems, titled “Children of the Drum,” he speaks about the resilience of Black performers.

According to Burnems, the poem is about “how we’ve shown up decade after decade to different genres and different mediums to celebrate our strength and our resilience.”

Kalana Amarasekara

Wallace also performed a number of poems under her poet name Lyrical Faith. One of them, titled “Best Friend Poem,” revolved around the influence Black joy and camaraderie has on friendships and strong communities.

“Black artistic joy and what that means and how you honor really special friendships and special relationships … is very integral, I think, to Black culture, just this aspect of community and … having shared inside jokes and relationships that speak to surviving this crazy … world that we are often a part of,” Wallace said.

The dinner concluded with a riveting performance from the UMass Insanely Prestigious Step Team (IPST). The team was captained by Christa Nagbe, who described stepping, as a dance, as using one’s body and voice to generate percussive music.

“I think [the dinner] contributes to … social changes very highly because it uses our words … and speech in order to make something powerful for us to get our voices across,” Nagbe said.

By the end of the dinner, spirits were high, hugs and handshakes were exchanged, and people left the Bromery Center with stories to tell from throughout the day. Black artistic freedom might have been celebrated over one weekend, but it can be celebrated every day as we acknowledge the power of the arts, whether hip-hop, spoken word poetry or stepping, and their ability to cultivate positive change within society.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.