From carvings by cave dwellers, to sketches by the artist Banksy, graffiti has the power to tell stories. But sadly, the ravages of time can impact these human renderings—from earthquake damage or the simple stroke of a paintbrush.

Before there were cameras everywhere, soldiers used letters and walls to document their tenuous existence. Whether people have mistaken them for hasty graffiti or sought to preserve them as historic artifacts, there are stories inside these scrawls. Empathy for these people has grown, along with the desire to know about their experiences.

In Virginia, there is a concerted effort to preserve graffiti left by thousands of soldiers who fought in the Civil War. Led by a modern-day Indiana Jones and supported by funding from the National Park Service and George Mason University, historians now have access to a state-of-the-art technology called multispectral imaging to uncover drawings left inside historic buildings.

Multispectral Imaging at Historic Blenheim

Cultural heritage and technology merged when engineer Mike Toth—aka Indiana Jones—ducked his 6’8” frame into the rickety entryway of Historic Blenheim in Fairfax County. Toth lifted cases of expensive equipment over the threshold—the same cameras he used to photograph a sixth-century Archimedes palimpsest and Lincoln’s copy of the Gettysburg Address.

It was late 2021, when Toth traveled a few miles from his home in Fairfax to record images of graffiti left by Federal troops occupying this Fairfax County plantation during the Civil War.

Toth was joined by Andrea Loewenwarter, historic resources specialist and protector of Historic Blenheim’s bevy of treasures. “Every one of these pictures tells a story,” says Toth. “We’re trying to capture all the stories we can, and Andrea is digging those stories out of each of these images. It’s a long process. It takes good eyes—and a lot of history.”

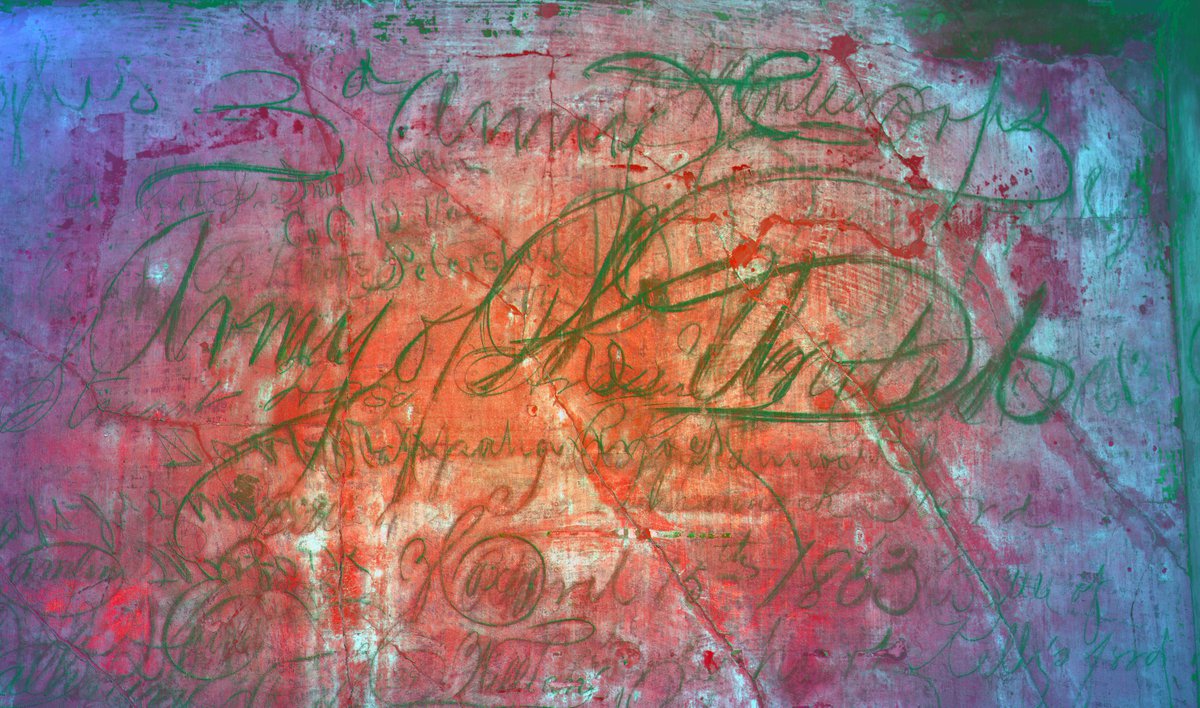

Inside the pitch-dark farmhouse, Toth shoots 20 pictures, lined up and itemized, with a 100-megapixel black-and-white camera. Two LED light panels capture the 161-year-old graffiti with ultraviolet, visible, and infrared light. Next, he combines the images to find areas with the best spectral response (or visual clarity), similar to the way an X-ray machine works. After the images are collected, Loewenwarter decodes what Toth’s images reveal.

He says it’s not just about technology, adding, “It requires skilled people to process and analyze. Teams working on these projects make them available to study worldwide.”

Federal troops occupied Blenheim Plantation from 1862 to 1863, a few miles from the battles of Manassas and Bull Run. After scrutinizing Blenheim’s collection of multispectral images, scholars deciphered more than 127 Civil War soldiers’ signatures, cross-referencing their names with companies in which they served. “In some cases, these are the only records we have of soldiers who fought in the Civil War beyond their enlisted papers and death records,” says Toth.

Blenheim’s Civil War Interpretive Center features a recreation of the house’s attic with drawings of muskets, cannons, flags, and ships. The upper level is currently closed.

The Graffiti House

At Brandy Station in Culpeper County more stunning scribbles are visible. Called the Graffiti House, marks were made by both Confederate and Union soldiers when Brandy Station operated as a field hospital.

“The house has a broad array of graffiti, including a dancing lady wearing a sunbonnet,” Toth says. There’s also a cartoon drawing of a horse’s hindquarters, meaningful, because the 1863 Battle of Brandy Station was the largest cavalry battle ever to take place in North America.

Peggy Misch, secretary of Brandy Station Foundation, says Graffiti House offers a window into another era. “It’s striking to think about men being there 160 years ago, not knowing if they would survive. It was their way to say: ‘I was here,’” Misch says.

Toth cataloged Brandy Station’s images, which will be available online. “These images will be available for anyone to read and interpret themselves. So our children’s children will have access to it,” says Toth. “By preserving and sharing them, you never know what we might find.” Or how future generations will value and interpret those findings.

Shenandoah Valley Civil War MuseumThe Shenandoah Valley Civil War Museum reopened in spring 2023 after an extensive renovation. The museum added new exhibits and artifacts, as well as a virtual reality experience featuring John Brown’s trial. In its previous life, the building was the Frederick County Courthouse in Old Town Winchester.

During the Civil War, it served as a jail, field hospital, and barracks. Soldiers from both sides scratched messages and their names on the walls. “Winchester changed hands 70 times, more than any other town in the Civil War,” explains Jay Richardson, park ranger for the Shenandoah Valley Battlefield Foundation. “So soldiers from both sides were hospitalized together.”

Among the doodles is a drawing of a northern soldier as a “jackass” and a poem that curses “Jeff Davis,” the Confederate president. When visitors arrive at the museum today, they receive a booklet about the graffiti. Richardson says the museum has committed extensive research on the names, regiments, and dates of capture. “We’ve put years into this work.” ShenandoahAtWar.org

Renee Sklarew writes about food, travel, and recreation for a number of publications.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.