For Elias Williams, the Hip-Hop Beat Machine Carries the Soul of Community

Hip-hop beat-makers are usually unseen. Not all sample-based producers are as reclusive as the torch-bearing loop artist Madlib, but even the most prominent among them are part of the backdrop. After all, a central function of their work is to produce scenery, as set designers for rap’s theatre of flamboyance. In this way, they are diametrically opposed to rappers, who plow into the foreground and draw the eye.

Beat-makers are often d.j.s, but even d.j.s, for all their in-the-room command, are, historically, vibe setters who must be both present and invisible. Though artists such as Kanye West, a beat-maker turned celebrity instigator, and Metro Boomin, a top-billed super-producer who is often credited as a featured performer, have challenged the binary, the dynamic has largely held. Nevertheless, the producer is fundamental to what hip-hop is. In essence, the earliest rap was turntablism; the merry-go-round—a technique, created by DJ Kool Herc, of clipping the rhythm breaks in soul records—led to sampling, the art of repurposing a portion of a recording to create a new one. Sampling is foundational to rap music as both an aural and a textual medium. As rap grew into a commercial juggernaut, the rapper’s standing rose as the beat-maker’s declined. It often feels as if the beat-maker’s recognition rarely aligns with his outsized impact.

In “Straight Loops, Light & Soul,” a black-and-white series by the Queens-raised photographer Elias Williams, the focus is on beat-making as a practice—its execution and exhibition. But in these photos the producers aren’t stars; they are operators and artisans. They are primarily machine-wielders, using samplers and M.P.C.s (which add sequencing capabilities) as tools, in solidarity with one another and in communion with their acolytes. The sampler is a machine of endless possibility, capable of taking any sound and conceiving it anew. Thus, beat-makers are on one side of an open line to the infinite; the machines are sacred, and gathering around one can turn a small room into a shrine to the past. The producer is reaffirmed as a cultural shaman. It is in this context that, Williams believes, one truly sees what the producer and the machine are capable of, how much artistry can be wrung out of a device on a table.

The writer Dan Charnas, in his 2022 book, “Dilla Time,” a cultural biography of the late crate-digging icon J Dilla, refers to the idea of the rap beat-maker as a conduit through which all musical memory flows, as the soul in the machine. “What hip-hop created, in the late 1980s and early ’90s, was a machine-assisted collage of human music,” he writes. “It turned the beatmaker into an alchemist of musical culture.” “Straight Loops, Light & Soul” was inspired, in equal parts, by Dilla and by “The Sound I Saw,” a book by the fine-art photographer Roy DeCarava, which compiled images from the Harlem jazz scene in the nineteen-sixties, mixing in tableaux from the city around it. Williams compares his project to sampling, riffing on DeCarava’s work as an act of transmutation. But, for Williams, the scenes captured within a back-room producer community are synonymous with those of everyday life.

In 2023, Williams, who had picked up beat-making as a hobby during the pandemic, sought to deepen his understanding of the form and his long-standing attachment to innovators such as Dilla. He found a group of producers hosting events on the Lower East Side, and told them of his aspirations—to shoot within their makeshift network, and to learn more about making beats. They welcomed him in, and the resulting series is imbued with the comfort and maneuverability of an insider.

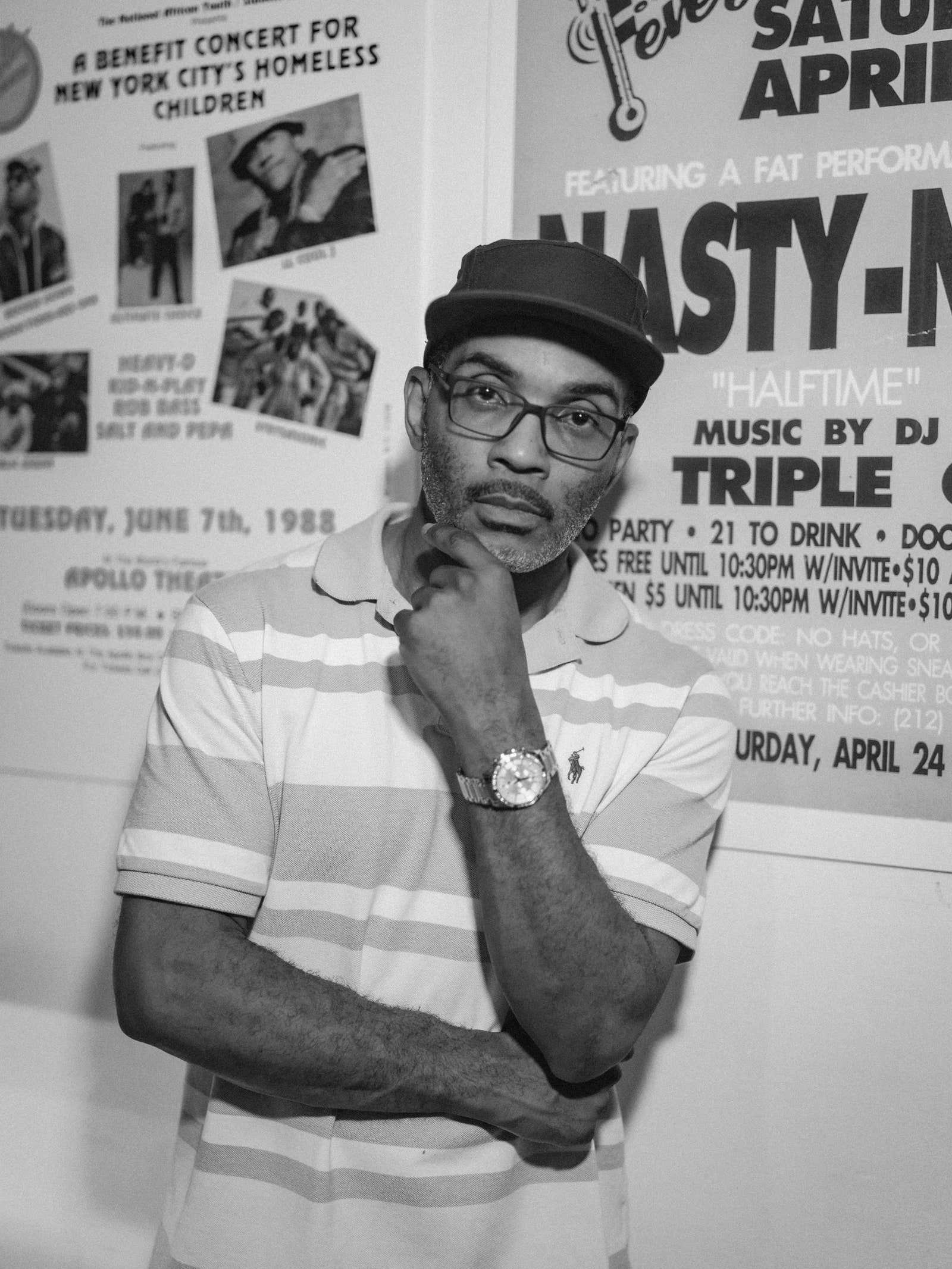

Most of Williams’s photography is portrait-based, and there is a bit of portraiture mixed into “Straight Loops, Light & Soul,” but the majority of these pictures are concerned with atmosphere. They bob through live events where beats are being played for an audience—a Dilla fund-raiser, producer showcases and meetups, the Lo-Fi Festival in Brooklyn. “You have fifteen minutes to find some expression in someone’s performance,” Williams told me. “Once I noticed that, it became just as much about the people who were around the room, engaging with the music.” Pictures of producers setting up in bars, dispensaries, art galleries, and co-working spaces also capture the soul emanating from samplers and the effect this has on repurposed dens. There are closeups of stank-faces, daps, acrylic nails turning knobs. Hands, lots of hands—outstretched, passing cords, clutching mikes, slipping vinyl out of sleeves, scratching records, tapping pads, scrawling signatures onto posters. Some images evoke the space through which sound travels. Others catch performers and spectators in moments of rapturous enlightenment, in the thrall of a locked-in groove.

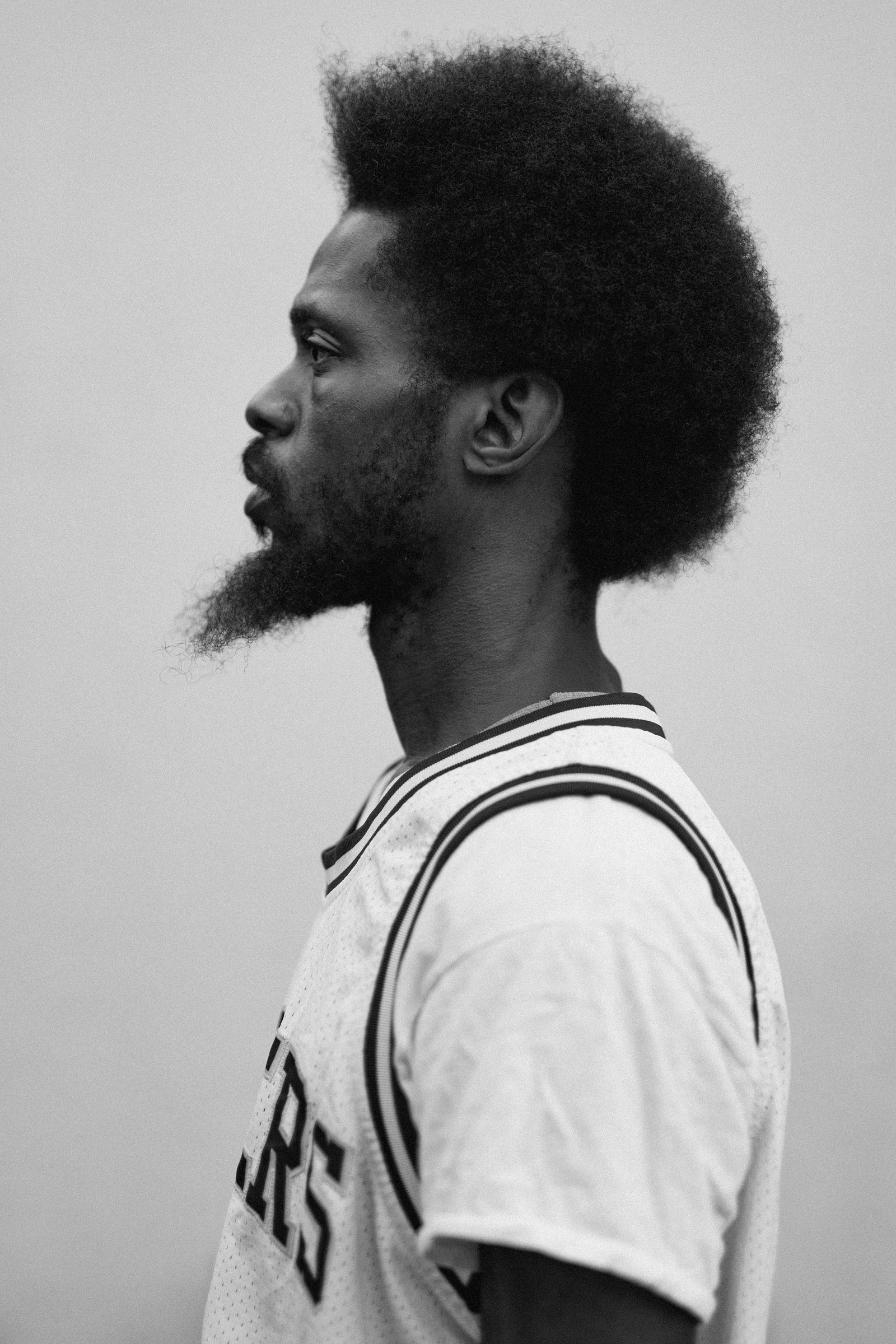

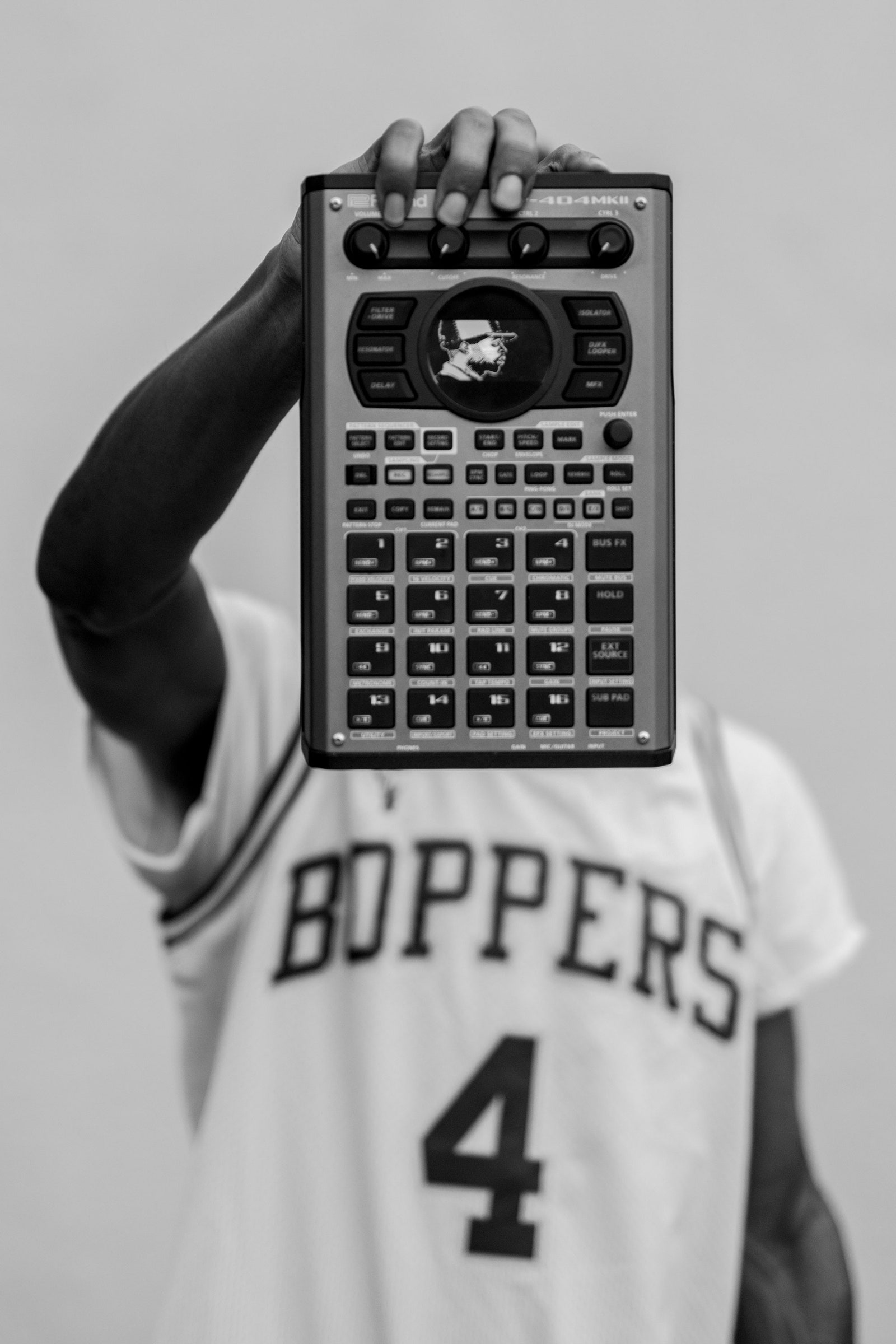

Williams occasionally uses composition to convey a sonic signature or identity for an artist. In some portraits, the producer DFNS poses with his SP-404 MKII (the latest in a series of samplers designed by the Roland Corporation), seemingly in reference to photos of the N.B.A. greats Michael Jordan, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, and Allen Iverson. DFNS’s beats often mine hoops for inspiration, so, fittingly, he holds his MKII as if crossing over, and wears a jersey bearing the name of his rap collective, the Boppers. Another producer, Zarz the Origin, who samples field recordings of city sounds, appears completely in shadow, skating under the Manhattan Bridge, his sampler illuminated in his hand like an enchanted object.

These images render the beat-makers as avatars for their sounds and for the machines that give shape to their various aural personalities, but the bulk of Williams’s collection revolves around performance, the use of the machines, the reactions they provoke, and the community built from a shared love of sampling as archival work. Most people don’t think of samplers and MPCs as instruments—in many ways, the music workstations are more akin to computers. They differ greatly from the horns and woodwinds and upright basses DeCarava sought to characterize, especially in action. Even Williams, a devotee of sample-based production, wasn’t initially sold on its live presentation. “I had my own preconceived notions of how people engaged with beat devices,” he told me. “I thought it was strictly hitting pads for fifteen minutes.” But samplers contain their own musicality, and the photos demonstrate how “playing” one can be a physical, expressive act. “It became a way, through everyone’s variations, to show their uniqueness. While everybody has the same device, they create a different thing. So their bodies become an instrument.” You can see those bodies as vessels in dialogue with both the music and the crowd, channelling time as each artist imagines it, in pursuit of a sweeping, inescapable connection.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.