Subscribe now for full access and no adverts

Underneath the fields of north-eastern France, caves that were used as shelters during the First World War contain a little-known legacy: thousands of inscriptions and carvings made by soldiers of all armies. There are an estimated 400 former limestone quarries with significant quantities of wartime ‘graffiti’ in the Hauts-de-France region that includes the Somme, Arras, Aisne, and Oise battle sectors. The traces range from hastily pencilled names to elaborate works of art. Fine drawings of regimental insignia reflect military pride. Later inscriptions such as ‘Hell’ and ‘Jesus Have Mercy on Us’ tell a different story. A race against time is under way to catalogue the inscriptions, because they are under threat from vandalism and erosion.

Subterranean stories

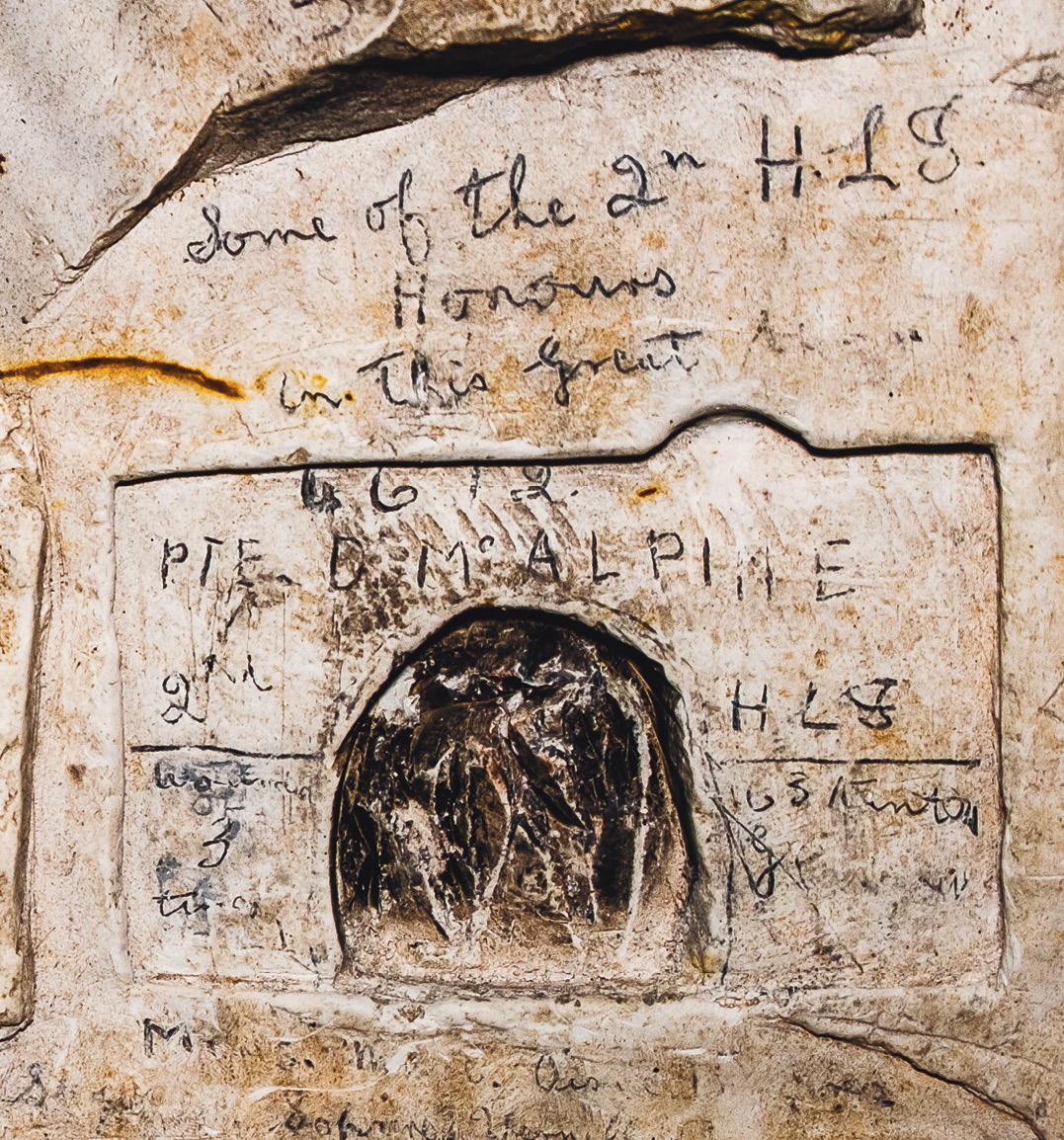

A tunnel under the Somme village of Bouzincourt containing over 1,000 British, Canadian, and Australian markings was closed in 2020 due to a risk of collapse. Dampness has caused many of them to dissolve into illegibility. Fortunately, the names have been logged by the French battlefield archaeologist Vincent Faivre, and researchers have created a detailed 3D computer rendition of the Bouzincourt caves to preserve their inscriptions for posterity. Each name stands for a story, and Faivre has been able to uncover hundreds of them. Private Daniel McAlpine of the 2nd Highland Light Infantry carved his service number, name, home town of Glasgow, and ‘Wounded 3 times’ in early 1917. The words ring with hope that he had had his share of bad luck, but he was killed in July 1917.

Walter Alfred Don Munday, a passionate mountaineer, became a Canadian infantry scout because he was familiar with difficult terrain and an expert with a map and compass. His job was to identify enemy positions and to lead troops where they needed to be. He wrote his name on the wall at Bouzincourt in late 1916 before suffering chlorine gas poisoning at the Battle of Vimy Ridge in April 1917. In October of that year, at the Battle of Passchendaele, shrapnel tore through his left arm and put him out of the war. He never fully regained the use of his left hand, but returned to climbing the peaks of British Columbia with his wife Phyllis. They gained fame as explorers and even have a mountain named after them: Mount Munday, 3,356m high and one of the principal summits of Canada’s Coast Mountains. Munday died in 1950 aged 62, of pneumonia – his lungs had never fully recovered from the gas. Phyllis hired a plane and scattered his ashes on the snowy peaks.

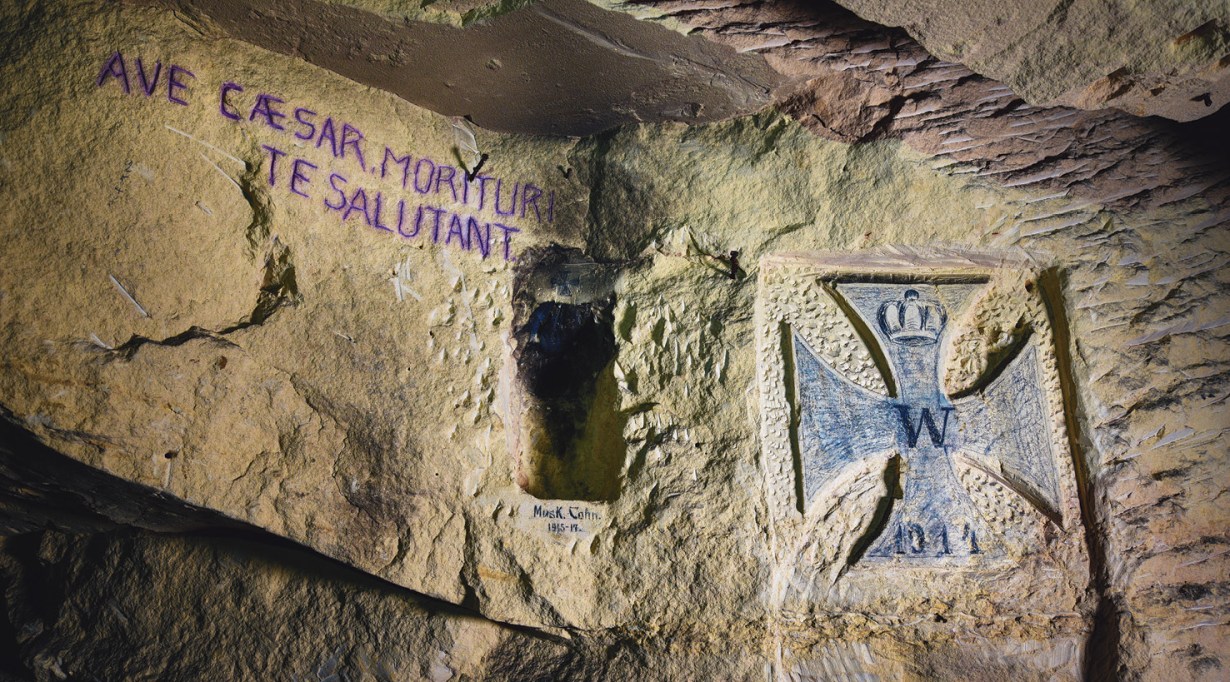

Down in the gloom of the caves that served as barracks, command posts, and hospitals, the soldiers’ thoughts were free to roam. The walls made perfect canvases for them. They knew their inscription might be their last trace – in very many cases, it was. So they wrote their name, rank, and service number. Or the name of a mate who had fallen. Or they created portraits of their wife or girlfriend, or that pretty waitress they saw in the cafe last month. Their farm animals back home, their pet dog. A poem. A patriotic slogan. A Christian cross. Using their knives, bayonets, or pencils, they copied the insignia of their regiment into the soft stone. They carved four-leafed clovers for luck and symbols of their nation such as Nelson’s Column, Marianne, the Iron Cross, the Canadian Maple Leaf. Or they just copied the label off a whisky bottle or a goddess off a bank note. The inscriptions reflect the variety of cultures that converged on the battlefields of France. At the same time, they illustrate what all the combatants had in common: a will to survive, to be remembered, to prove their worth. Of course, some of the artworks depict big-breasted nudes or male genitals. This was graffiti after all, created by boys. The traces are undistorted by time. They cut through decades of myth, propaganda, and shifting trends of remembrance. Over a century on, they provide new insights not just into the war but also the human response to extreme conflict.

The French archaeologist Gilles Prilaux came across one of the biggest concentrations of inscriptions in 2014 when he was examining caves beneath the village of Naours, north of Amiens. He was scouring the ground for coins and musket balls from the Thirty Years War when he looked up and saw some pencil writing on the wall. A name, a service number, and ‘59th Battalion’. He found that the walls were covered with pencilled names of Australian soldiers, and began trying to identify them. At first, it was like deciphering hieroglyphs. Prilaux learned that NSW means New South Wales, VC stands for the state of Victoria, and COY means Company. A total of 3,200 names have been logged at Naours, of which 2,200 are Australian. Prilaux obtained public funding for student research projects and devised a museum about the Naours graffiti that was opened in 2020.

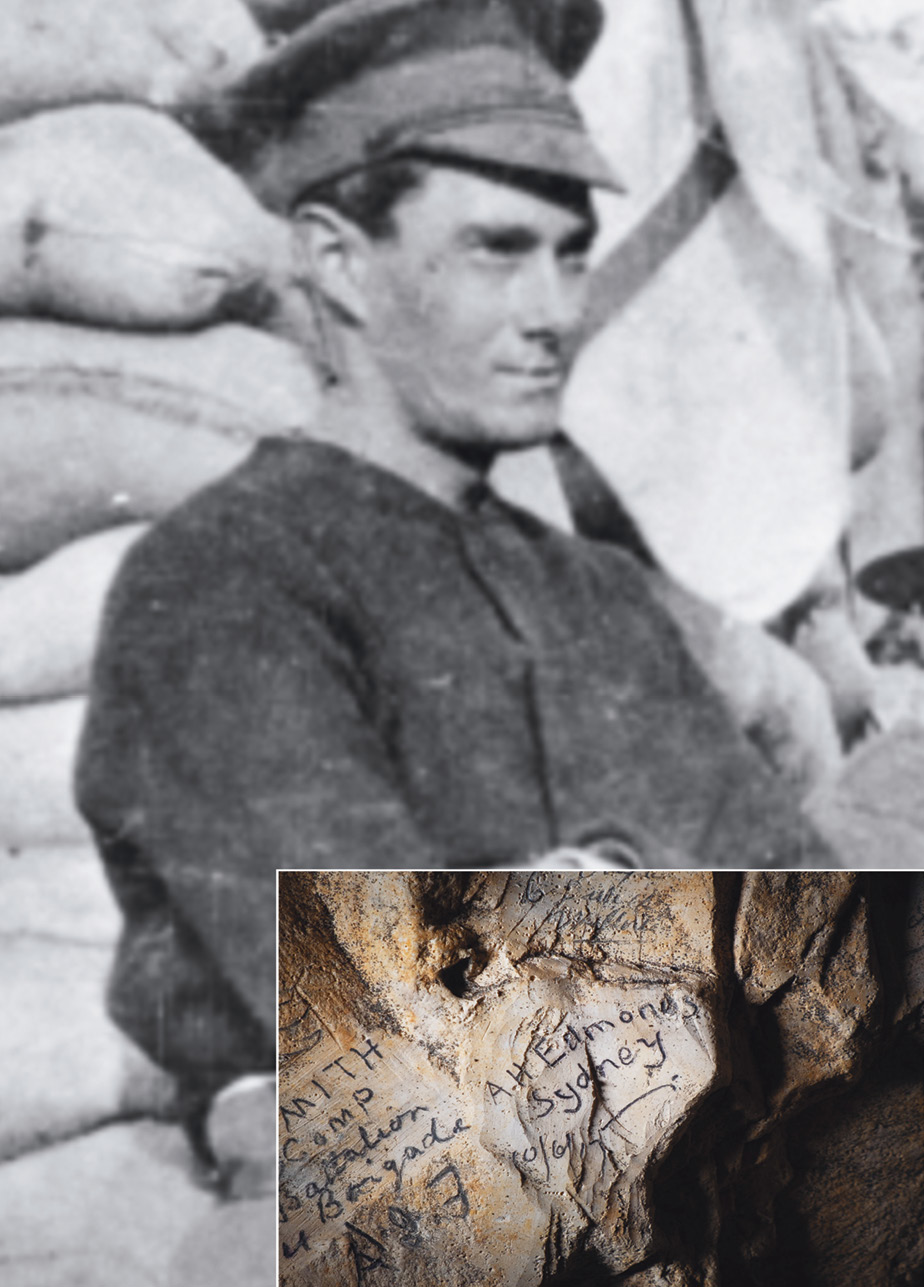

The Naours caves are unlike others in that they were a tourist attraction even during the war, visited by many soldiers on rest and recuperation. They included Lance-Corporal Adrian Henry Edmonds of the 3rd Australian Division Signals Company, who visited Naours in May 1917. Edmonds, in his mid-20s, from Sydney, had a dangerous job – laying telephone lines across battlefields – but he was also a keen sightseer. His diary conveys both the horror of the fighting and the beauty of the landscapes he travelled through. In July 1916, on a train to the Somme, he wrote of ‘hills covered with wheat interspersed with red poppies and cornflowers’. On Boxing Day 1916, he took a walk in Delville Wood, which had been one of the bloodiest battlegrounds of the Somme that summer. His description reads like an indictment. ‘Shattered trees and trenches, shell holes, military gear and corpses by the score are scattered everywhere. British and Germans mixed, some with bayonets through their bodies, others with limbs blown off – facts which show only too plainly the terrible contest for this Wood… If only those who are responsible for this terrible war could see these silent forms!’ Edmonds died in 1968.

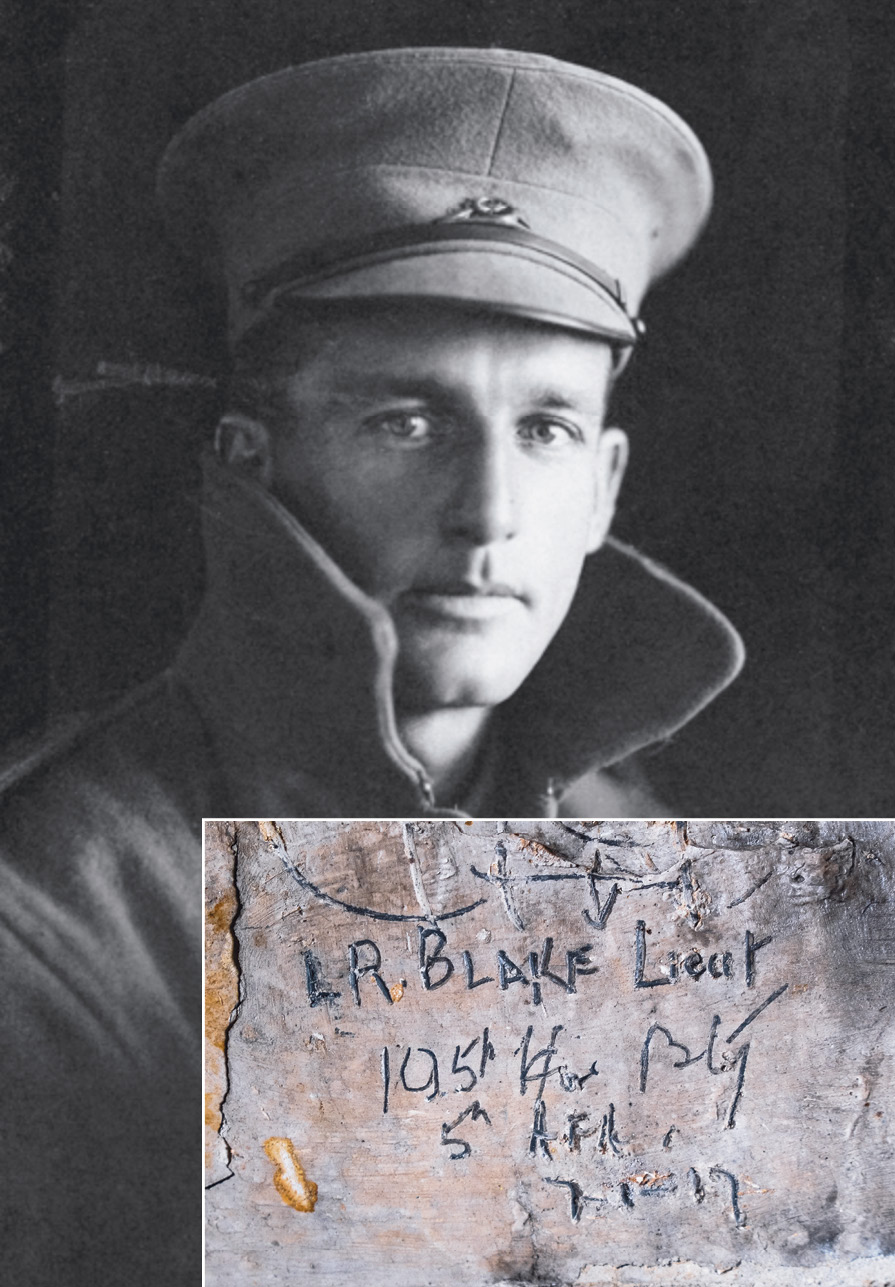

Another soldier who wrote his name at Naours was the Antarctic explorer Leslie Russell Blake, a peer of Scott and Shackleton, who was awarded the Military Cross by King George V at Buckingham Palace in June 1917. The Australian lieutenant, a trained surveyor, was tasked with crawling into No Man’s Land to map the German lines for artillery barrages. After being wounded twice and promoted, he could have seen out the war in the safety of staff headquarters. But he chose to be with his men, and was killed 39 days before the Armistice.

From quarries to shelters

The quarries were dug centuries ago to extract limestone for houses and churches. Most went out of commercial use in the 19th century as bricks became more economical. After the front stagnated in September 1914, both sides seized these ideal shelters and fitted them with electric light and telephone lines, vestiges of which are still visible today. Some are time-warps containing bully-beef tins, boots, gas masks, and empty bottles of pinard, the cheap red wine treasured by the French troops. While Naours is open to visitors, most other quarries are out of bounds on private land and dangerous to enter.

‘Some contain live munitions that have become degraded and are too dangerous to remove,’ said Jean-Paul Batteux, a retired firefighter who was a cave-rescue specialist and has been exploring underground sites in France for more than 40 years. He is author, too, of the book Explorations souterraines. ‘These places contain the history of the Great War in France,’ he added. ‘It only takes one person to get in and steal, destroy, or damage something. Then a piece of history is lost forever.’ Batteux is one of a handful of dedicated French cave explorers, historians, and archaeologists who spend their free time scouring subterranean sites for graffiti.

Even the most experienced can get lost in these labyrinths, some of which extend for kilometres. ‘If you get lost, always follow a wall to the right or left and you will eventually find the exit,’ said explorer Bernard Waite. In a quarry near the Chemin des Dames ridge, I came across an artillery shell that had turned green. My enquiry ‘Does that contain gas?’ was met by a Gallic shrug. ‘Let’s hope not,’ my guide grinned.

Even though a number of the sites have been designated as national monuments, there is no publicly funded programme to preserve or study them. Some are the domain of local heritage societies that view outside researchers with suspicion. Countless names have yet to be traced. On a recent visit, I came across a name written on the wall of a quarry near the river Aisne: Private W H Howard of the Sherwood Foresters, dated 10 May 1918. A search on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission’s website listed a Private W H Howard of the regiment’s First Battalion as having died on 18 February 1919. It could be him. Further research is needed.

There are intriguing national differences. The British, Canadians, and Australians often wrote their names and even home addresses and drew their regimental badges.

The French copied images from bank notes and had a weakness for nudes. Their commanders picked out soldiers with a talent for sculpture – some were professional artists in civilian life – to adorn the caves with rousing artworks and regimental panels listing senior officers. The Germans, who occupied some quarries for years, left comparatively few personal traces and tended to confine themselves to functional signage such as ‘To the kitchen’. A common inscription is the slogan Gott Mit Uns (‘God With Us’ ) that was stamped on their belt buckles. Hatred is conspicuous by its absence. Troops tended to respect each other’s graffiti when caves changed hands, perhaps because they knew they were all going through the same inferno.

One cave entrance near the town of Bucy-le-Long is festooned with three regimental badges carved by the British, French, and German units that occupied it. Alfred Brisley, a sergeant in the 1st Battalion of the Hampshire Regiment, carved the first badge in September 1914. ‘To while away some of my time I have carved a huge monogram of the Regiment on the face of the stone walls of the cave at the entrance,’ he wrote in his diary. Just ten days earlier, he had lost his best friend in the explosion of a German shell in the town hall of Bucy-le-Long. ‘We buried him the same night close by, together with many civilians and French soldiers,’ wrote Brisley. Doing something creative, it appears, was a way to distract oneself from the horror, at least for a few hours. After the British left, the French 45th Infantry Regiment moved in and carved their emblem next to Brisley’s. In January 1915, the cave was abandoned to the German Prinz Carl von Preussen Grenadier Regiment, which chiselled its own badge. There they remain to this day.

By making their mark, soldiers sought to show they were part of a momentous chapter in history – and to leave a personal trace in a mechanised war in which the individual counted for little. ‘The messages on the walls are like someone putting a piece of paper in a bottle and throwing it into the sea, to say “Don’t forget us: we were here”,’ said Gilles Chauwin, the President of the Chemin des Dames Association, who oversees the Froidmont quarry near the city of Laon.

Froidmont contains one of the richest collections of inscriptions under the Western Front. It is known as the ‘Quarry of the Yankees’ for its hundreds of traces made by soldiers from the US 26th Division, consisting of National Guard troops from New England. They were there for six weeks in February and March 1918, and wrote their names in big and bold lettering that resembles the font of advertisement billboards. Their traces pulsate with the energy of fresh troops ready to get into the fight. In that sense, they augur the outcome of the war.

Chauwin, 70, has fitted the entrance with a steel gate, modern locks, and a CCTV camera. He has been decorated by the US military for his work to preserve the site. Two 5m ladders lead down into a maze where one’s torch beam falls on Buffalo Bill, Uncle Sam, Native Americans with feather headdresses, and Squares and Compasses of Masonic lodges. It is a profoundly moving place – a veritable art gallery that expresses wild, youthful individuality, in stark contrast with the uniformity of the ranked headstones in the Western Front’s mass cemeteries. ‘I see it as my duty to protect this place,’ said Chauwin. ‘When I’m no longer here, I’m going to get cremated and go down there. To be with my mates.’ Froidmont is in safe hands. Others are at the mercy of intruders, with mutilated sculptures and inscriptions defaced by spray paint.

A fragile legacy

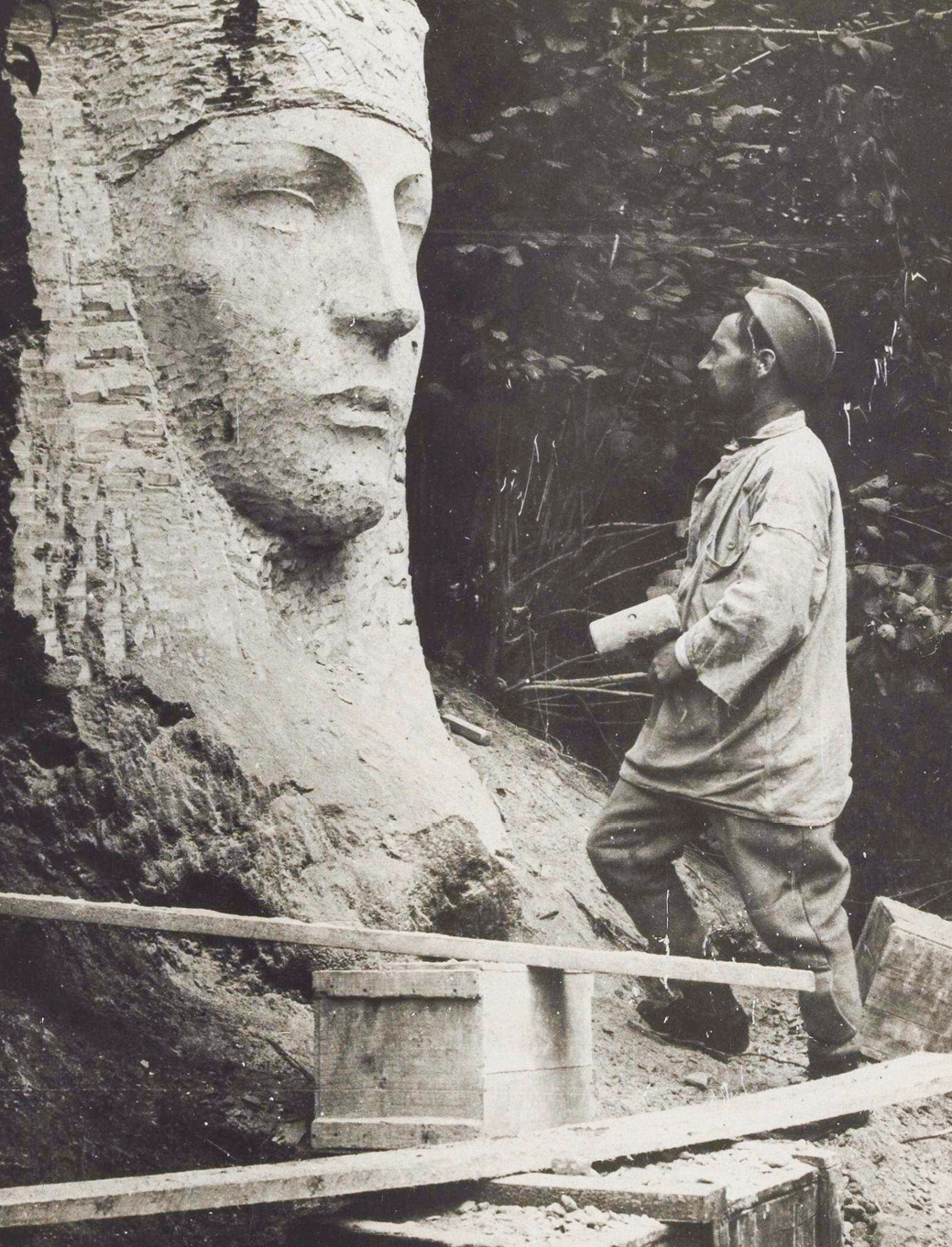

On a wooded hill near the river Oise, a magnificent sphinx guards the overgrown ruins of a French command post that resembles a temple city lurking in the rainforest. The sphinx was crafted by the sculptor Louis Leclabart, who served as a stretcher-bearer. A few metres away stands another work of his, Joan of Arc clutching her sword – now exhorting the troops to drive the Germans from French soil. Both are chipped and weather worn. But France’s leading expert on First World War graffiti, the historian Thierry Hardier, said moving them or any of the soldiers’ artworks into museums would tear them out of their context. ‘Even making moulds of them can damage their surfaces. The best solution is to make photographic 3D renditions.’

Hardier said the quarries needed more funding and better protection, but admitted there was a dilemma. While they were as worthy of UNESCO World Heritage status as the 139 cemeteries and memorials that received it in 2023, granting them such recognition would increase the number of visitors to dangerous, unprotected, and isolated sites, and thereby accelerate their deterioration. ‘We have to stress the importance of these places, but we have to be careful about mass tourism, because many sites are dangerous to enter,’ Hardier said. ‘There’s no point in promoting them unless we have the means to protect them and to welcome people who might be interested.’

Further Information:

David Crossland’s Whispering Walls: First World War graffiti is published by Amberley.

Other key sources of information about the graffiti include:

• Thierry Hardier, Traces rupestres de combattants (1914-1918) (in French).

• Jean-Paul Batteux, Explorations souterraines dans les calcaires du Lutétien (in French).

• Gilles Prilaux, Matthieu Beuvin, Donna Fiechtner, and Michael Fiechtner, The Silent Soldiers of Naours: messages from beneath the Somme (in English).

All Images: copyright David Crossland, unless otherwise stated

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.