Breaking Out

The Bronx Museum

September 8, 2024–March 30, 2025

New York

In the early 1970s, Leonard Hilton McGurr became famous. Taking the name FUTURA 2000, he did art in the subways. The handout for his current Bronx Museum exhibition includes a photo, from 1981, of him with his peers, Kenny Scharf and Keith Haring. At that time, their graffiti was seen as a political failure, revealing that the city could not control its public spaces. Then soon enough, when more effective policing was developed, FUTURA 2000 stopped making art in the subways and worked in other, more sympathetic popular venues, such as rock concerts, for example painting while the Clash performed. And more recently he has been hired to brand goods for such luxury businesses as Comme des Garçons, BMW, and Nike. Now, dropping the 2000 and simply calling himself FUTURA, he runs a design studio.

This political history of graffiti, which has taken FUTURA into both the commercial marketplace and this museum, is complex. In two books Joachim Pissarro and I have discussed what we called “wild art”: art outside the art world that has moved into the museums.1 Graffiti is a textbook example, an art form developed for the subways now put into the art museum. But what we didn’t perhaps consider in sufficient detail is how the artist needs to adapt for the art to survive that change. In the subway a street artist like FUTURA 2000 needs to very quickly catch your eye. But when he moves into the museum, responses to his art slow down and it gets judged in relation to other paintings. And then what’s demanded in a retrospective like this is that the ensemble of artworks add up to define a satisfying total work, the story of an artist’s development. Subway wild art is pitted against advertisements, while in the museum, that art becomes the subject of interpretation, just like old master paintings.

When Pietro Perugino (1452–1523) was criticized for repeating himself, Giorgio Vasari tells us he replied that “I have used the figures that you have at other times praised, and which have given you infinite pleasure; if now they do not please you, and you do not praise them, what can I do?” The complaint was that he had failed to vary his successful compositions. An artist, it was implied, needs to develop. But why was that important? After all, as Perugino reasoned, his painting done for one city would not usually be compared with works for other places. Only in a retrospective do we make such visual comparisons. The complaint recorded by Vasari thus anticipates the culture of the modern museum. It’s no accident, then, that Perugino faced the same situation as FUTURA 2000, for like graffiti, altarpieces were painted for sites outside of the gallery or art museum. And so how these paintings are seen changes when these works were taken from churches or subway cars and moved into the museum.

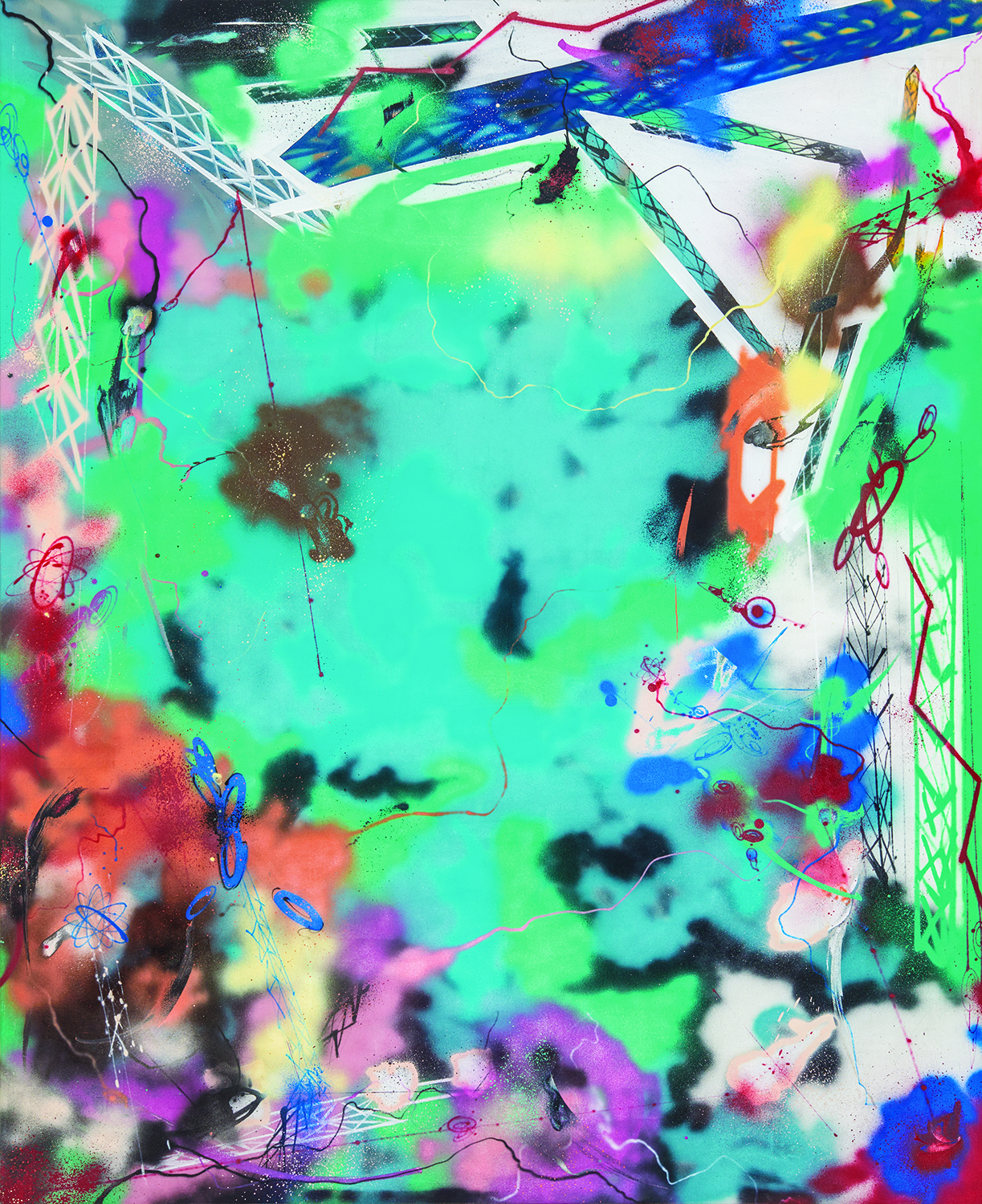

The converse of Perugino’s dilemma, which we find here, is that Futura 2000’s paintings are too varied, revealing much knowledge of recent museum visual culture but not showing consistent personal development. Sometimes here you see affinities with Ed Ruscha’s Pop art, as in Untitled (1980), with FUTURA 2000’s chosen name ‘FUTURA’ spelled out in caps. In other works, however, there are associations with the “bad” painting of David Salle—Under Metropolis (1983) is an instructive example. And sometimes you find gestural color field paintings like Sports in Space with Air Force Blue (1984) or AbEx gone wild, as in Bill (2020). The whole history of modernist painting is present in one work or another. In this setting, then, FUTURA comes off as a very good, but not a great painter. He has astonishing skills, but lacks the single-minded focus required to truly thrive in the gallery context. Perhaps, then, he is best seen rather as a conceptual artist, for Breaking Out is a great exercise in applied aesthetics. But however a visitor chooses to understand FUTURA’s individual works, what is made most clear by the Bronx Museum’s retrospective is the fact that his graffiti-derived painting is fundamentally transformed by being displayed in this new setting, and that it is changed in ways that necessarily challenge the aesthetician.

- On wild art see my books with Joachim Pissarro, Wild Art (2013) and Aesthetics of the Margins / The Margins of Aesthetics: Wild Art Explained (2018) with extended discussions of graffiti.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.