One cold night in December 2019, toward the end of a month-long sojourn in New York City, I was eager for a taste of home. I was in the midst of my third year of a Ph.D. program in English at UNC Chapel Hill and I had spent the last three weeks researching in the archives of Harlem’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture for my dissertation.

I saw a post on Instagram announcing that North Carolina producer 9th Wonder would be playing some of his beats in a Monday showcase at the Bowery Electric on the Lower East Side. Though I was working as a teaching assistant for the Grammy Award-winning producer at the time, I had never heard him actually play a live set before. Without hesitation, I hiked over from my little third floor sublet in Bushwick to check it out.

That night was enveloped in the kind of rare, unforgettable magic that only New York can produce. I grabbed a drink and looked to my right to see Jay-Z’s engineer and advisor Young Guru towering over me.

I descended the stairs to the basement stage, where a lineup of heavyweight super producers including Diamond D (credits include Tribe Called Quest, The Fugees, and Fat Joe); Statik Selektah (Nas, Freddie Gibbs, and Styles P); and Easy Mo Bee (Notorious B.I.G., 2pac, and Craig Mac) played beats early into Tuesday morning.

Punctuated by emcee performances from hip-hop’s underground past and present, the night reached a crescendo when Easy Mo Bee took out the original floppy disks to Craig Mack’s “Flava In Your Ear (Remix)” and Biggie’s “Warning,” slid them into his SP 1200 sampler, and hit play.

The walls — slick with the condensed sweat evaporated from frenetic hip-hop heads — felt like they would crumble from the power of the fervent energy coursing through the room.

As I took the L train back at 4 a.m. and dreaded returning to the sterile archive rooms in just a few hours, what I didn’t realize was that I had just stumbled across the work of one of the most monumental figures in North Carolina hip-hop history: Gene Brown.

Brown has curated the legendary lineup of producers that night, part of the Bowery’s Mobile Mondays series, to mark his own 46th birthday.

An icon in the Charlotte music scene, Gene Brown has built himself up to be a foundational part of hip-hop history — not as an emcee, producer, or b-boy (though he was once adept at all three) — but as a record dealer.

A virtually constant presence in Charlotte’s scene since the 1990s, Brown has served as the careful ear that provided records to worldwide cultural icons like Questlove, Q-Tip, Just Blaze and 9th Wonder. Through his encyclopedic knowledge of records, wrought through countless hours digging in record crates, he has quietly and carefully influenced generations of artists since his childhood in Greenville, NC.

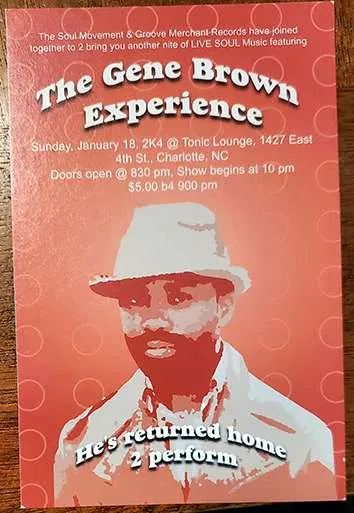

Inspired by similar parties he once curated in NYC, Brown hosted his first Gene Brown Beatdown, a producer showcase event featuring Just Blaze and Jake One, at the old Event Masterz space on May 14, 2022.

Since then, Brown’s Beatdowns have featured producers like Diamond D, Buckwild, Lord Finesse, Nottz, and many more in venues ranging from the Booth Playhouse to the QC Soundstage to CAM Raleigh during Dreamville weekend.

A three-night, three-year anniversary event is scheduled for May 16-18 in the new Event Masterz space on Remount Road.

The itinerary includes a performance from Royal Flush with guest DJ BINK! on Friday, May 16; a slate of producers set to take the spotlight on Saturday night including Bangladesh (“A Milli”) and DJ L.E.S. (“Life’s a Bitch); then a panel discussion/Q&A on Saturday afternoon with NYC A&R exec and record producer Kyambo ‘Hip Hop’ Joshua.

Carolina born and bred

Born in Durham in 1973 — the same year as the art form he has dedicated his life to — Brown’s family moved to Greenville in the late 1970s when he was in kindergarten. He developed a hunger for music while digging through his dad’s records, who also ran some small clubs in Greenville.

Ahmad Jamal’s iconic 1970 jazz record The Awakening — the second track of which later became the source material for Pete Rock’s production of Nas’ “The World is Yours” (1994) — inspired Brown to start playing the piano.

The record would later serve as the main source material when Brown began making pause tapes, an early and rudimentary production technique that involved dubbing cassettes by manipulating the pause and record buttons on a tape recorder.

Whereas early accounts of the hip-hop South tend to start with OutKast’s Southernplayalisticcadillacmuzik (1994) in Atlanta or the Showboys’ “Drag Rap” sample (1986) in New Orleans, Brown describes Greenville as a vibrant ground in which hip-hop was taking root in the early 1980s.

“Greenville was pretty hip for a small town,” he insisted during a recent conversation with Queen City Nerve.

Between northerners migrating to small eastern NC towns to reconnect with family, college kids coming home from school and underground entrepreneurs looking to corner untapped drug markets, Greenville kids were able to soak up and partake in all the latest trends of hip-hop.

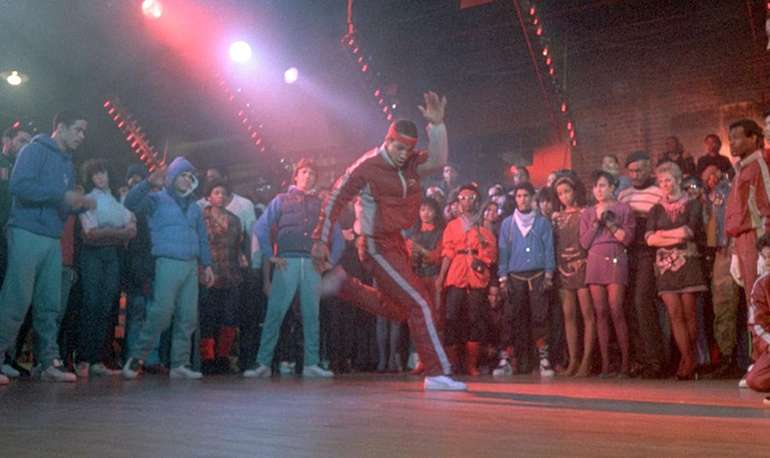

They were inspired by mixtapes and films like Wildstyle (1983) and Beat Street (1984).

Young Greenville folks like Moses Barrett III, Brown’s seventh grade classmate at Greenville Middle School, was steeped in the culture, Brown recalled.

“He could sing. We know him as a singer,” he said. “But he was a rapper too. He was rapping all the time.”

Barrett and Brown would battle in the back of the bus on the way to and from school. Barrett, of course, went on to take the stage name Petey Pablo, writing hits like the Timbaland-produced “Raise Up,” our state’s unofficial hip-hop anthem.

By 1987, Brown’s family moved to Charlotte in pursuit of better opportunities. In eighth grade at that point, Brown was awed by Charlotte’s more robust music scene.

Public access TV shows like The Don Cody Show featured local talent, inspiring Brown to pursue his artistry that much more passionately. He tried on different rap names including MC G, Smoothie G, Chilly G, and Lord G Smooth — the latter inspired by underground stalwart Lord Finesse.

Following in his father’s footsteps, he went to North Carolina Central University (NCCU) in 1992 on a basketball scholarship. However, his experience at the school quickly soured due to friction with his coach.

He tried transferring to Winthrop University to continue his basketball career but was sidelined due to an injury. Brown was more interested in music than basketball anyways. He shifted his focus more deeply to music while taking classes at York Technical College in Rock Hill.

Brown continued to make beats and rap with his NCCU-based group, Vurbul Divursité. Around that time, he met Dres from the NY-based underground group Black Sheep.

Living on Charlotte’s east side at the time, Dres was interested in connecting with Brown after hearing one of his beat tapes through a friend. He ended up using one of Brown’s beats for “As I Look Back” on his first solo project, Sure Shot Redemption, in 1999.

As Brown elevated his musical practice, he began taking more frequent trips to New York, including one in 1993 to shop demos with fellow members of Vurbul Divursité. He met a young entertainment lawyer named Reggie Ossé, soon to be known as beloved hip-hop radio personality Combat Jack.

Lord Have Mercy of Busta Rhymes’ Flipmode Squad took him to the headquarters of Loud Records to see if they could get their demo in front of someone in the industry. While there, they ran into one of hip-hop’s most beloved icons.

“We were talking about the roster on Loud, so we’re naming Mobb Deep and Cella Dwellas and Wu-Tang, and all of the sudden, out of nowhere, somebody busts in the middle of the little circle we were in,” he recalled.

It was Wu-Tang emcee Ol’ Dirty Bastard.

“He was like, ‘Did I hear somebody say something about Wu Tang?’ It was crazy. He busted in the middle of about five or six guys. We were like, ‘Yeah we was just talking about the roster.’”

Satisfied by their answer, ODB went on his way through the building.

Building his own name

These sorts of not-so-chance encounters marked Brown’s musical career while helping springboard his reputation as the record dealer to your favorite hip-hop producers.

Brown’s journey as a record curator began through his own interests as a producer. When he was short on cash, Brown would barter others for records that he wanted to sample. On his trips to New York, he realized the records he was selling were rare and extremely valuable.

He recalled one particular trip to New York in 1995 with Len Funk and Craig Williams: “I took one book, one little box. Craig and I made a ridiculous amount of money. I knew then, this is something I need to be looking into.”

As his network grew, so did his capacity to trade and sell records, yet he was still invested in his performance career.

After graduating from NCCU in 1999 with a degree in Business Administration, he moved back to Charlotte to pursue music full-time. Looking back at that time, he described a Charlotte scene that was vibrant but increasingly fickle as hip-hop’s national market turned its ears toward the party-inflected hip-hop coming from the South.

In 2003, Brown’s frustrations with Charlotte’s uneven support for its musicians came to a head. He was booked to do a show in Atlanta with Dwele and left a week early to find a band to play live instrumentation. While there, he found a scene that was supportive and vibrant.

Though Dwele had to cancel the show, Brown decided to stay in Atlanta, collaborating with local artists and selling records to the More Dusty than Digital record store.

Atlanta’s promise began to fade in time. Though Brown had a great, affordable spot in Grant Park, North Carolina proved an easier starting point from which he could travel to New York and other cities.

In 2006, Brown welcomed his daughter into the world. With a newborn to support, he made the tough decision to focus fully on record dealing rather than making his own music.

Despite his reluctance, his reputation as a sample-whisperer to hip-hop’s star producers had become enormous by that time. When he moved back to Charlotte in 2008, he had provided the samples for Lloyd Banks’ “Cake” (produced by Fatin “10” Horton), Jeezy’s “Go Crazy” (Don Cannon), Jay-Z’s “Oh My God” (Just Blaze), and Destiny’s Child’s “Girl” (9th Wonder).

He was in regular conversation with folks like Questlove of The Roots and Q-Tip of A Tribe Called Quest. He leaned into curating records for the best of hip-hop’s producers full-time.

“I had this customer base that was developing, so I took it serious to where I would prepare crates or boxes or records for a certain person,” he explained. “I would [treat it] almost like a nine-to-five type of job. I would get records and go in my studio and play stuff and put dots beside the things that I knew would work for this type of sound or this type of [producer].”

Showcases and Beatdowns

As Brown got older he saw the potential to leverage his rich musical connections into hosting some of the greatest hip-hop showcases that North Carolina has seen.

Brown’s idea for a “beatdown” began in New York in 2013, when he was invited to throw a party for Bowery Electric’s Mobile Mondays series. He had recently bought a collection of nearly 200,000 7-inch records, or 45s.

The Bowery invited him to throw a 40th birthday party using the 45s. He started there and began throwing parties and invite his producer friends like Rich Medina, Kid Capri, and Just Blaze to DJ the celebrations.

These parties, like the one that I stumbled into in New York in 2019, were so well-received that he wanted to bring them down to his adopted hometown of Charlotte. However, the Queen City simply didn’t have the same history as New York when it came to hip-hop’s rich cultural traditions.

An opportunity arose when 9th Wonder and DJ Clark Kent (Notorious B.I.G., 50 Cent, Jay-Z) were put in charge of planning a string of events to promote Dussé, Jay-Z’s cognac brand.

Using the 2019 Bowery Electric Show as the template, 9th Wonder pitched a beatdown in Charlotte and Jay-Z bit. The Gene Brown Beatdown was ready to go — but perhaps the world wasn’t ready for it.

Read more: Revisiting Little Brother Debut ‘The Listening’ After 20 Years (2023)

The pandemic derailed the earliest plans for the collaboration and it wasn’t until 2022 that Brown was able to finally throw his inaugural event. The venue was packed wall to wall with hip-hop fans, slick with sweat on the humid May evening, but folks forgot about the literal heat when the beatmakers started spinning.

This weekend’s three-year anniversary festivities will be about more than an opportunity for Charlotte hip-hop heads to hear dope music. Gene Brown’s story shows how the South’s voice has been a part of hip-hop culture long before André 3000’s indictment of hip-hop’s New York-centrism at the 1995 Source Awards.

The South has always been a vibrant site of hip-hop expression, as it pulls from the archival dredges of the past to articulate a new present.

Southerners have always had one foot in the past and another in the future. Folks like Brown have stayed creating, driving the culture toward spaces not yet imagined by the central stalwarts in New York and Los Angeles.

The periphery generates new centers — spaces not yet here that can help us imagine otherwise. Looking back on that night when I first encountered Brown’s work in New York, it wasn’t the city that produced the magic; it was Brown.

His life is a testament to imagining otherwise, and the three-year anniversary of Gene Brown’s Beatdown will be not just a retrospective but a celebration of what his imagination might produce next.

SUPPORT OUR WORK: Get better connected and become a member of Queen City Nerve to support local journalism for as little as $5 per month. Our community journalism helps inform you through a range of diverse voices.

Sign up for The Charlottean by Queen City Nerve

Join over 25,000 Charlotteans in getting our articles delivered straight to your inbox.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.