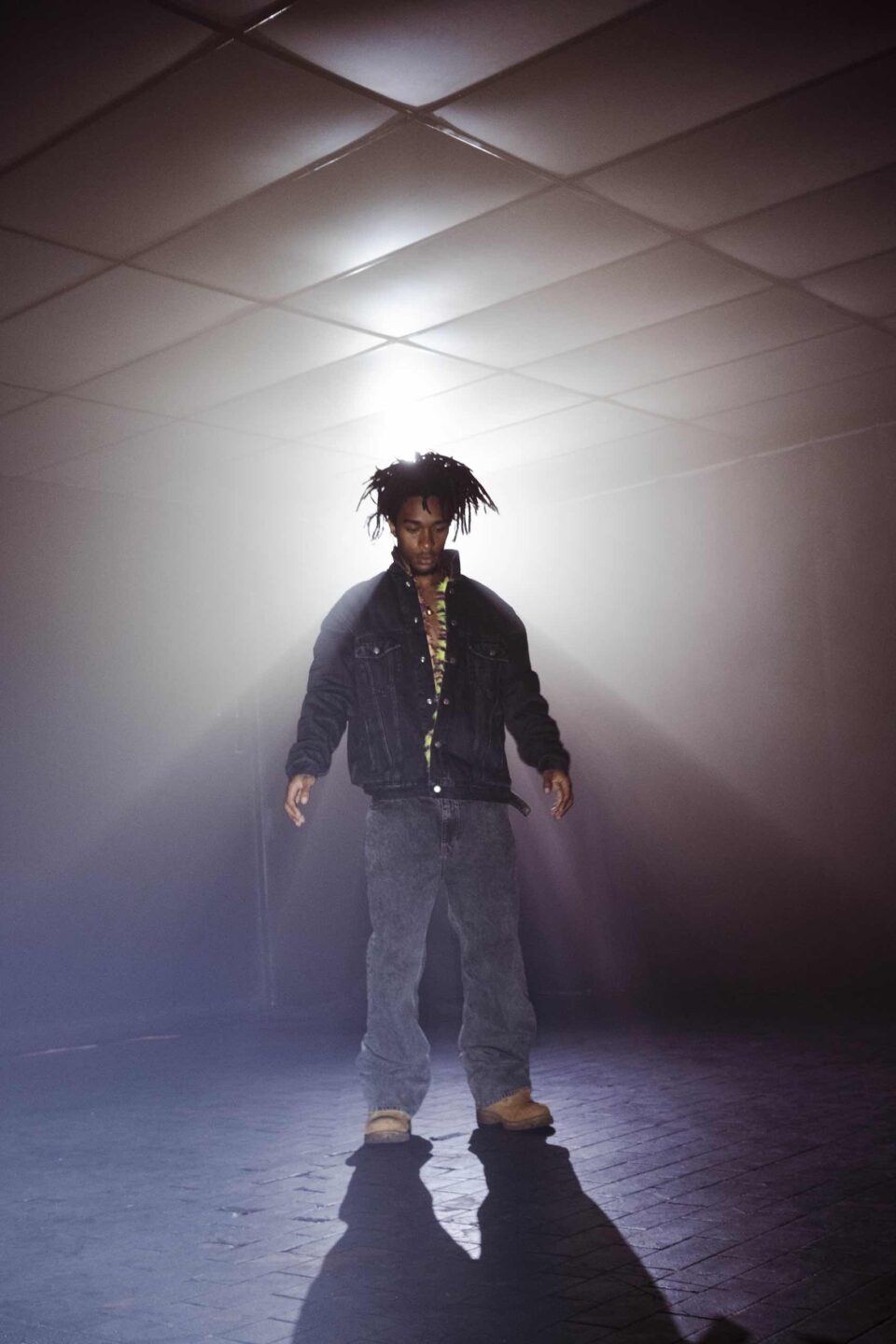

It’s hard to listen to “The Old Guard Is Dead,” the second track from Ghais Guevara’s new album Goyard Ibn Said, and not believe him. There’s the Just Blaze–esque, horn-driven beat that’s full of operatic vocal samples and drums that slap like a bitterly cold winter day. Guevara—raised in Philly, currently living in London—cooked up the beat himself and dances on the graves of his opps as he triumphantly states: “Aim from the moon, rose from the ghetto.” It’s both a fact and a way of life, a mission statement and a constant reminder for every time you fall into cliché, bad habits, or phoniness.

It’s this sincerity that animates Goyard, his first project for Fat Possum Records. Ghais is unabashedly obsessed with both radical philosophy (generally centered around Black liberation) and luxury goods—in other words, the good life more generally. This development of personal style that blends the socialist political with commerce was born out of necessity. “You have to find your way to not be the nerd, you know what I mean?” he tells me. So, we pimp out the Frantz Fanon with Fendi.

Dichotomy is at the heart of the Ghais Guevara project, but it’s precisely this willingness to be contradictory that’s helped him cultivate such a loyal, excited, and eager-to-spend fanbase. Guevara sells records in an era that’s hostile to the very concept. By keeping his fans engaged, he keeps them active, eager to support his career. “I’m a passionate person,” he explains. “It’s in my music. I give them something to relate to, something to discuss.” The Goyard doesn’t pay for itself, after all.

With Goyard Ibn Said out now, we spoke with the rapper about the album’s namesakes, growing up radical, leaning into community, and more.

How did you first learn about Omar ibn Said?

I encountered him by messing around with people who read books. You just come across things that catch your eye, and I decided to pick up his book and read it. I just felt the whole tale of being this dude from West Africa, brought over and converted to Christianity alongside his Muslim faith. It’s this tale of being in a new land. It’s not exactly the transition of getting put into the music industry, but it was the analogy I was drawn to.

How has your experience with the industry evolved? I imagine when you first started you were wide-eyed and optimistic.

Yeah, it was kind of crazy. It’s like you’re going to this new world and you’re going to see what it’s like beyond the ocean. Then you’re like, “Everybody over here is an idiot, what the hell is going on?” It’s not completely deflating. I’ll admit I was jaded at first, but when you realize this is something you can navigate, as long as you trust the right people, it’s easier to be optimistic.

Are there some artists that you can point to that have helped you out?

Yeah, McKinley [Dixon]’s big on that. He calls me out of the blue every now and then, still checks up on me. Sweet dude. DJ Haram was one of the first artists trying to tell me what it is and what I need to do, just straight up. As the label stuff happens, you just get to meet more and more [behind the scenes] people rather than artists within the industry who can give you ideas and stuff.

“I wanted to make the album representative of my fluctuations and why I fluctuate—why we all fluctuate. I don’t understand why we all try to do that to ourselves.”

You got ELUCID and McKinley on the album. Do you view yourself in that world of rap music?

I see where I fit within it, you know what I mean? I try not to act like I have a place. The world takes you to a lot of places. I mean, here I am in London. You never know what you gotta adapt to.

The way you blend cultural issues and Black activism with the joy of rap culture is intoxicating. How did you strike that balance?

It’s just kind of by nature. I grew up a revolutionary kid, so there was obviously always an ethical and moral disconnect with a lot of the folks that I was growing up with just because they’re not educated in the same way that I was. You have to find your way to not be the nerd, you know what I mean? Not be the Dick Gregory motherfucker always trying to preach and stuff.

Talk to me about growing up and your education. Who taught you about politics?

Both of my parents. They actually met at one of those rallies. My mom was in a MOVE rally, my pops was at an anti–death penalty rally, and that’s where they collided. It’s literally in the bloodline, that sort of thing. At home, we were surrounded by books.

Were you always enchanted by what they believed in?

Oh yeah, for sure. A little too enthusiastically. I definitely eventually pushed away from them—certain points, certain lessons I didn’t want to understand. I had to find my way within that, as well.

Are you pretty active politically in your community?

I was coming up as a teenager up until my early twenties. Now I’m not as outside. I still got my shit to talk and all that, but yeah.

Were you part of the Philly rap scene growing up?

I came up through the internet. It wasn’t even like I had to go to these artist showcases and all of that. I wasn’t really doing a lot of that networking stuff. I was very narcissistic, in a way. “I’m better than all these n****s, why do I have to do that?” Whether that’s true or not, that’s up to everybody else. It’s hard to be from Philly because of its proximity to New York and all the resources. But the talent’s really bubbling there. It really is.

How long ago did you start writing Goyard Ibn Said?

A little over a year ago. There were probably some beats in there that are a little older than that. I don’t think I got the concept of how I wanted to present it ready until maybe four months before I turned it in.

How did you want to present it?

Originally I wanted it to just be side A, side B—here’s me doing some poppy stuff, here’s me doing underground hardcore stuff. It just felt weird trying to divide myself into two like that. I wanted to make the album representative of my fluctuations and why I fluctuate—why we all fluctuate. I don’t understand why we all try to do that to ourselves. So as I was able to reflect more and more on myself I realized that these two sides were two sides of the same coin.

“You have to find your way to not be the nerd, you know what I mean? Not be the Dick Gregory motherfucker always trying to preach and stuff.”

Is there a philosophy that runs through this album?

It’s a perspective on what it means to be influenced and inspired by hip-hop, and how that reflects culture in a general sense.

Do you think about these songs in a live setting when you’re recording them?

Oh, for sure. That’s the point of a rapper, you know what I mean? Master of ceremonies and we’re supposed to know how to rock the stage. That’s something I take seriously. If I can’t do a verse live in the studio, then it’s not going up on the stage. I try to really make sure I can get that down.

How do you balance doing your lifelong passion as a job while still having to make money off of it?

I have such a good relationship with my fans. When I say, “Yo, I need to do something for money,” it’s like, “We get you, bro-bro.” It’s the best part about coming up organically and especially within a community that’s more politics-centered.

This might be a crude way of putting it, but since your fans buy your music, why do you think they value art more than someone who’s just streaming playlists on Spotify? What about your music attracts passionate fans?

I’m a passionate person. It’s in my music. I give them something to relate to, something to discuss, something to dislike and hate. It’s not just cookie-cutter, same old, same old. I ask questions, I’m receptive, things like that. The human aspect really does help with that. FL

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.