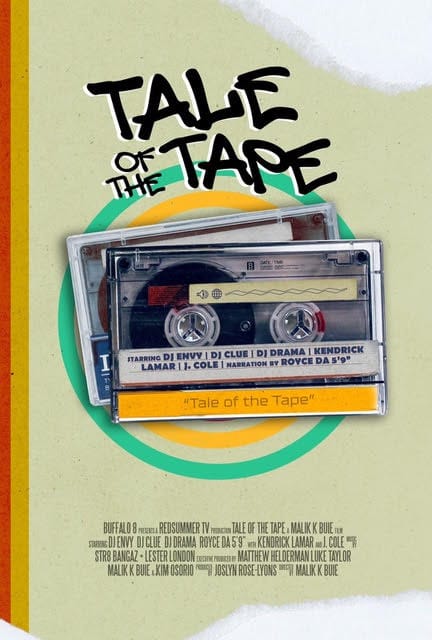

In 1981, Toni Morrison famously said, “If there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.” Director and filmmaker Malik K. Buie is more of a movie guy, but the point stands. The sentiment was the spark that spawned Buie’s latest work, Tale of the Tape: How the Mixtape Revolutionized Hip-Hop, an hour-long documentary that chronicles the evolution of the hip-hop mixtape and the underground kings who paved the way.

Tale of the Tape—which is co-executive produced by DJ Envy, veteran journalist and television producer Kim Osorio, and Buie—is the product of more than a decade of documentation. Buie, who’d formerly shoot and produce BET’s Rap City before working his way up to director of content for the network, would lug his camera everywhere, capturing and earmarking footage for his passion project (often while on the clock at his day job). That piecemeal approach allowed him to stockpile recordings of icons turntable like Kid Capri, DJ Drama, and DJ SNS; blog era superstars like J. Cole, Big Sean, and Kendrick Lamar early in their careers; and legends like Prodigy before his departure. The final result is a comprehensive look at a subculture that has gone undocumented for far too long.

“This story is for everyone from young kids to the OGs,” Buie says of Tale of the Tape (now streaming via Prime Video, Verizon, and Spectrum On-Demand). “It’s important that we control our narrative.”

Buie, who now runs his own production company Red Summer TV, is proud of what he created, yet already looking to the future: a sequel that focuses on hip-hop’s DVD explosion. For now, he hopped on the horn with LEVEL to break down how he brought Tale of the Tape to fruition—and why you need to tune in.

LEVEL: Where did the initial inspiration for Tale of the Tape come from?

Malik K. Buie: I’m a producer, director, and filmmaker, so I always look for the most interesting yet obscure angles to telling great stories. Hip-hop raised me. Through my years of work, I found I was documenting and producing with a lot of artists and DJs. I was a producer for BET’s Rap City for years and I found that with all the DJs and major artists who’ve had some real taste of success, the mixtape was the connective tissue. It was the one thing that they all had in common that pretty much launched them. It was only right to tell this story.

When you embarked on this, did you feel mixtape DJs and their history was being documented?

No, it felt like it did not exist. When I was at Morgan State [University], me and some of college friends had a store called Da Source. It was this hip-hop shop where you’d get mixtapes and commercial CDs. I would interact with a lot of DJs and I always felt they weren’t being properly appreciated. To be honest, the mixtapes sold more than the commercial music we had at the store.

Years later, after I graduated school and I was working, I did a project for Camille Cosby where she sent me to the South to do interviews with our little beknownst civil rights leaders—like someone that started the NAACP chapter in Jackson, Mississippi, things like that. We all know Medgar Evers, King, and Malcolm X. But there are a lot of people that contributed to the movement, so this has to be documented. This is important. One day it clicked with me: The same thing goes for DJs, the Brucie Bs and the Kid Capris. Their stories need to be documented. It’s an important part of our culture.

I learned a lot from the documentary—my entry point to mixtape DJs starts right around DJ Clue. It’s dope to see the figures who were instrumental in the evolution of the mixtape every step of the way.

Right. It’s kind of like when you watch sports—people might say basketball starts with Jordan. No, there was a lot more before that. He is one of the greatest, but as you watch older games, you’re like, “Wow, I had no idea that he got from that person. He took this move from here. He got this type of strategy from that person.” That’s the same thing with DJs. You love DJ Clue but there are things he took from SNS, from Kid Capri. Then there’s some things he came up with on his own, which makes him one of the greatest of all time.

You captured footage of J. Cole and Kendrick Lamar early in their careers, as well as late legends like Prodigy of Mobb Deep. Can you walk me through the process of filming over the course of 10 years?

Ten years is kind of a soft marker. It may be 12, to be honest. Me and my executive producer, Kim Osorio, had so many shoot days, calls, and meetings. The very first interview was DJ SNS in Harlem. The second interview was with Brucie B at some bar lounge in the Bronx. Those guys are notoriously late. I think we got DJ Clue and DJ Envy three-to-six months later.

When I was producing Rap City, we used to have this BET activation and showcase called Music Matters where we would find talent that was on the cusp of [blowing up]. J. Cole was an artist that we were like, “Yo, this guy’s about to be it.” We were able to interview him. Some of these interviews came on the back end of other productions, like with Big Sean. The Kendrick footage probably happened two years later. I was working at the Hip-Hop Awards in Atlanta and Kendrick happened to be in town to promote Section.80.

At this time, all these years ago, I’m directing, I’m camera op[erator]—a little bit of everything. After every shoot, Kim would look over the footage, pick the best sound bites, and we start crafting the story. There were so many holes, but we kept filling them. DJ Craig G at a pizza shop in Connecticut. Meek Mill at Howard Homecoming. We were able to get Joe Budden when he’d just started his podcast. I went to his house in Jersey City and he had pit bulls or whatever kind of dogs. I’m like, ”Bro, that dog is huge!”

It was like a neverending thing. Once we got close to the pandemic, we had all this footage and some downtime to lock in on the edit. Kudos to Kim, who kept me honest with certain things. There was a point where we had to say, “Look, this is it.” The last thing we put in there was DJ D-Nice and Club Quarantine, because we felt that was really what the new mixtape had become: DJing on IG live and playlists on different [streaming] platforms. But it was great. It didn’t feel like some arduous job putting this together. This was really a labor of love.

When you’re working on something for so long, how do you know when you’re done?

As a perfectionist, you’re never done. But the reality is, when no more dollars can be spent, that’s when you’re done. Me, Kim, and Envy just had to come to a consensus. We watched it and loved it. We was like, If there’s anything else that needs to be done, it would be done on part two. But we’re extremely happy and excited that it’s out now and the world gets to watch this.

What was the most challenging aspect of this whole journey?

The most challenging thing is figuring out what to leave on the cutting room floor, because these things become a part of you. You really want it to be part of the entire film, and sometimes that doesn’t happen due to time constraints or a clearance issue. But the beautiful part is being able to put the stuff on YouTube or IG.

What’s next for Tale of the Tape, and more broadly, projects you’re working on?

We are going to do a second installment of Tale of the Tape [covering the] DVD era and the artists that rose to fame from that. Super excited about that. As for me, I run Red Summer TV. We’re a full-service production company and we do a lot—we livestream Essence Fest, we did a house documentary that’s on Comcast, we’ve got a few projects in the mix. There’s one we’re doing called Don’t Sell Grandma’s House, a podcast series on gentrification. It’s a very emotional story of the fallout and destruction of a family over a home in Brooklyn. We’ve got several projects coming that we’re very excited about.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.