Melbourne is Australia’s street art capital — but it wasn’t always the case.

Kamilaroi artist Reko Rennie remembers graffiti starting to appear on the city’s walls and in public spaces, when he was a kid growing up in Footscray in the early 80s.

It was an exciting time in the city thanks to the arrival of urban street culture from New York, introduced by cult films like Breakin’ and the book Subway Art, a “landmark photographic history” by photographers Martha Cooper and Henry Chalfant.

The young Rennie, already into hip hop and breakdancing, was immediately drawn to the world of graffiti.

“It was a natural progression,” he says.

He felt empowered by the whole process, from stealing spray paint to painting murals — and he wasn’t alone.

The 80s saw a “massive explosion” in Melbourne’s graffiti subculture as artists made their name — literally — creating works on walls, rail carriages and train lines.

“I’d already been exposed to a lot of political graffiti in the late 70s and early 80s around Melbourne … about land rights, feminism and Aboriginal rights,” he says.

“It really resonated with me as a kid, that you could make a mark and have a voice.”

Four decades later, Rennie has moved on from the world of graffiti and is now an internationally recognised, multidisciplinary artist.

Reko Rennie’s Message Stick, which was purchased by the National Gallery of Australia in 2012. (Supplied: Reko Rennie)

Known for infusing art and politics, Rennie is now the subject of two new shows: REKOSPECTIVE, a major survey exhibition at the Ian Potter Centre at the National Gallery of Victoria, and Urban Rite, a collection of new paintings on show at Sydney’s Ames Yavuz Gallery.

From Footscray to Venice

Rennie was a teenager when he discovered the work of Howard Arkley, an Australian artist who would become a significant influence on his artistic practice.

He felt a connection between the visual aesthetic of graffiti and Arkley’s use of block colour and black outlines in his airbrushed paintings of suburban Melbourne, such as Shadow Factories (1991).

“I thought I could do something like that … I could take these skills that I’ve learned from the street and apply them in a kind of visual language, but use my background, use the history of Aboriginal rights in this country — or the lack of them — and then use my artwork to make a political statement about the past, the present and the future,” he says.

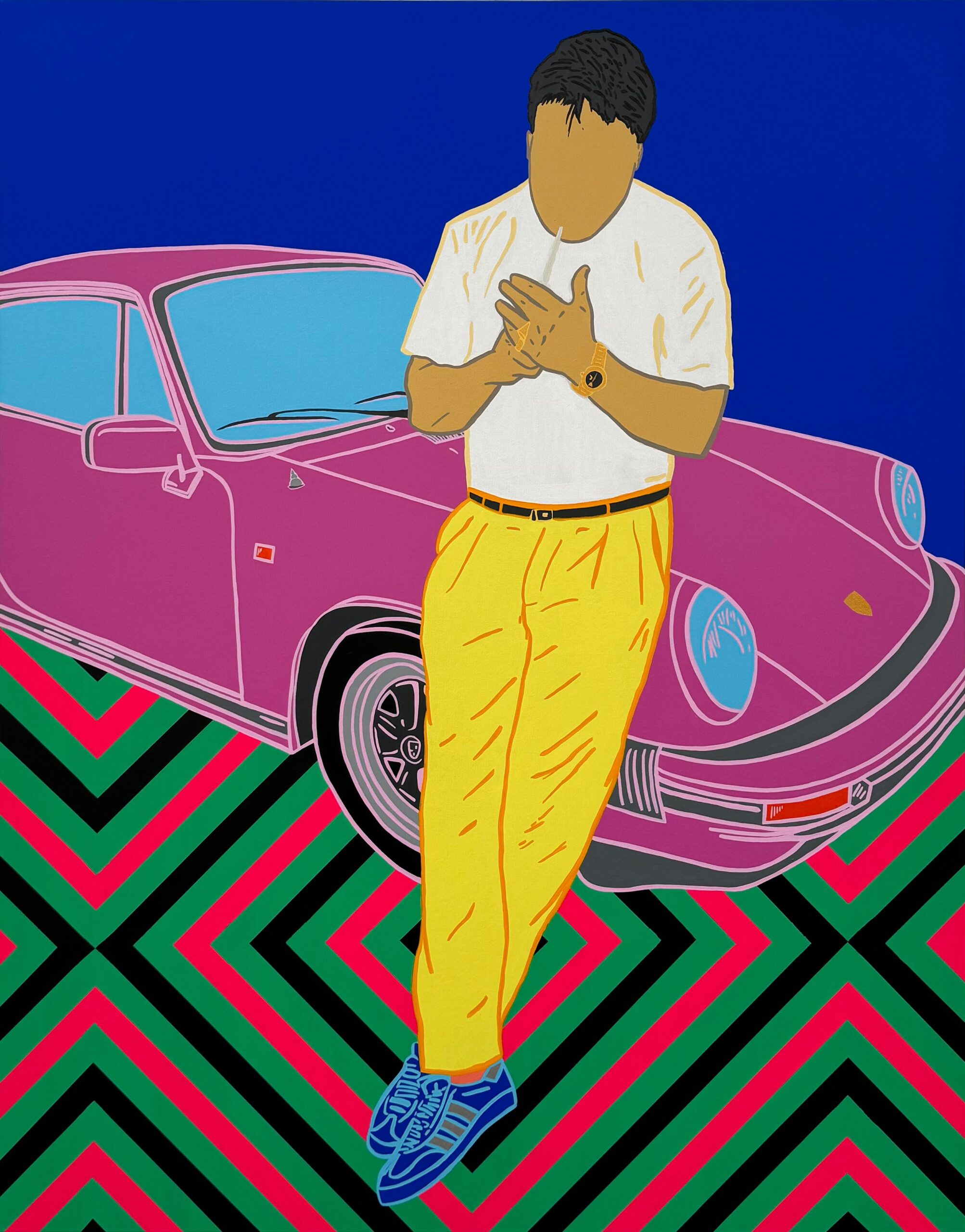

Black Nouveau is a new work by Rennie, as part of his Urban Rite exhibition. (Supplied: Reko Rennie/Ames Yavuz)

Although he loved art, a succession of “shitty art teachers” who were dismissive of his work put him off seriously pursuing it as a career.

Instead, he became a journalist, but kept making art in his spare time.

He developed a style grounded in the aesthetic of street art and traditional Kamilaroi iconography, including distinctive diamond designs referencing tree carvings made by his ancestors, known as dendroglyphs.

In 2008, he won a Victorian Indigenous Art Award and, the following year, secured a three-month residency at the Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris.

He says the international recognition had the effect of legitimising his work in the eyes of the Australian art world, and his career took off.

“I quit full-time work to go [to Paris] and haven’t looked back.”

Rennie has always found an international audience for his work, which has been shown at galleries and exhibitions across the US, Europe, Asia and South America.

Regalia — a 2015 work now held by the Art Gallery of New South Wales, featuring the repeating symbols of a crown, an Aboriginal flag and a diamond painted on a 2.5-metre aluminium canvas — appeared in the Personal Structures group show at the 56th Venice Biennale.

The motifs of a crown, an Aboriginal flag and a diamond are repeated in Rennie’s Regalia series. (Supplied: Reko Rennie/blackartsprojects)

Rennie returned to Venice in 2017, when his three-channel video work titled OA_RR — documenting his road trip in a customised 1973 Rolls Royce Corniche to his grandmother’s birthplace on Kamilaroi country in north-west NSW — featured in the 57th Biennale.

“I’ve always wanted to have more of an international profile rather than just being a local Australian artist,” he says.

“I felt like, ‘Why should we as artists settle for domestic representation? We should be sharing our work on the international stage.'”

Remember the colonised

Unlike his forebears — including his grandmother, Julia, a Kamilaroi woman who was part of the Stolen Generations — Rennie has the freedom to speak out against authority, and it’s a responsibility he takes seriously as an artist.

“For many Aboriginal families, particularly this generation … there’s a real obligation to make sure that our voices aren’t silenced anymore,” he says.

“It’s very important that our history isn’t forgotten.”

Reko’s work often combines the bold street art aesthetic with distinctive Kamilaroi iconography.

One of his best-known works, Remember Me (2020), serves as a memorial to the genocide of First Nations people carried out by the colonising Europeans.

Rennie first used the phrase “remember me” in a mural he painted in North Fitzroy 20 years ago.

“It’s about remembering us as a nation, as a community, as Aboriginal people,” he says.

“It’s about remembering us as we are, as humans and citizens.”

In a commission for Carriageworks in Sydney, Rennie illuminated the phrase in red neon lights to mark the 250th anniversary of when Captain Cook made landfall at Botany Bay in 1770.

The NGV acquired the 15-metre work in 2023, and it now appears in REKOSPECTIVE.

“It’s a personal, powerful statement about the effects of colonisation,” Rennie says.

“It could be about any community that has been colonised.”

Rennie hopes visitors to the REKOSPECTIVE and Urban Rite shows leave with a greater appreciation of the diversity of Aboriginal Australia.

While Indigenous art is synonymous with the dot paintings of the Central and Western Desert, Rennie says these works constitute a small part of contemporary Aboriginal cultural expression.

“The majority of Aboriginal people in Australia live in urban environments. We don’t live on the fringes of a dusty desert plain or in the outback,” he says.

“We are not a monoculture. We’re a very diverse culture made up of patrilineal, matrilineal societies, 280 different language groups, tens of thousands of dialects and multiple religious and cultural esoteric practices.”

REKOSPECTIVE: The Art of Reko Rennie is at the Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, Melbourne, until January 27, 2025.

Urban Rite is at Ames Yavuz Gallery in Surry Hills, Sydney, until November 9.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.