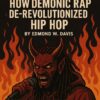

Todd Boyd started writing his new book, “Rapper’s Deluxe: How Hip Hop Made the World,” about three years ago, though in many ways, it’s been underway for decades.

“I’ve been telling that in many ways, I’ve been writing this book since I was 9 years old,” the University of Southern California professor says. “Before I knew I was writing it, I was writing it.”

Boyd turned 9 in 1973, the year generally accepted as the birth of rap, and that’s where “Rapper’s Deluxe” begins, at an apartment party in the Bronx, where a DJ named Kool Herc showed a new way of spinning records.

The book ends, neatly, if not entirely by intent, 50 years later, when hip-hop culture had reached a peak far from its underground origins, a handful of its biggest stars playing the halftime show at the Super Bowl, a sign of the music’s dominance of the culture.

“The fact that coincides with the anniversary is one thing,” says Boyd, the Katherine and Frank Price Endowed Chair for the Study of Race and Popular Culture,and a professor at its School of Cinema and Media Studies. “But I think it’s a story that unfolded from the ’70s to the present. I needed all that time in order to tell the story.

“Ten years ago, 20 years ago, this book couldn’t have been written,” he says. “It could only have been written now. One of the main reasons is because you needed all that time for this to kind of fully unfold and reveal itself. And that’s where I came along.

“As I was watching that Super Bowl halftime performance that I ended the book with – at SoFi Stadium with Dr. Dre and Snoop and Kendrick Lamar and that group – I realized, you know, this is it,” Boyd says. “This is the most mainstream stage in American culture. And, you know, 30 years ago, there’s no way possible that Dre and Snoop would have been performing at the halftime show of the Super Bowl.

“When you get to that Super Bowl stage, it’s a strong indication that you’ve reached the sort of center of mainstream society. And you can talk about things happening afterward, but the sort of larger point has been made.”

‘Root to the fruit’

“Rapper’s Deluxe” traces the evolution of rap music and hip-hop culture with chapters organized by decades, each packed with photos around Boyd’s essays on artists, trends, history and pop culture.

Its name is a play on “Rapper’s Delight,” the 1979 Sugar Hill Gang track that’s credited as the first rap single. But Boyd makes clear that while its success put rap on the radio and exposed its new sounds to listeners far from its birthplace in New York City, there was a whole lot more going on that decade behind the music.

“The point I was trying to make in that ’70s chapter was we’ve had examples of, if not rap specifically, hop-hop culture for a long time before a lot of people even knew it,” he says. “The seeds for what we would later call rap music were being planted. And if you use that metaphor, you know, you plant seeds, they don’t grow right. That takes time.

“So listening to Muhammad Ali rhyme before his fights to me is part of what would later be identified as hop-hop culture,” Boyd says. “Listening to Richard Pryor on his comedy albums. Watching blaxploitation movies.”

“Rapper’s Delight” is a historical marker, he says. But the groundwork was laid in communities where Ali and Pryor and “Super Fly” and “Shaft” were popular, neighborhoods where Black veterans came home changed by Vietnam and Black Panthers and activists such as Angela Davis had support.

“I like to say we go from the root to the fruit,” Boyd says. “The seeds were planted and eventually those seeds bore fruit. All of those things were happening in the ’70s. Later, they’re very visible in hip-hop.

“I start the ’70s chapter with that story about the week that DJ Kool Herc threw the sort of legendary party,” he says. “The No. 1 movie at the box office that week is Pam Grier’s film ‘Coffy.’

“Twenty years later, there’s a rapper named Foxy Brown” – after the Pam Grier title role in the 1974 blaxploitation film of the same name – “and Quentin Tarantino is making ‘Jackie Brown’ starring Pam Grier,” Boyd says. “There’s a connection there that nobody anticipated in 1973, but you can see the influence of that by the time you get to the ’90s.”

‘Suburbs to the hood’

Rap, like many musical genres before it, experienced growing pains on its way to its worldwide popularity. But throughout the ’80s, Boyd writes that a combination of factors, including the rise of hip-hop-themed movies, fashion, and art, as well as rap’s appeal to celebrities and sports figures and their fans, helped it burst into the mainstream in unprecedented ways.

Unlike earlier Black American music such as blues and jazz, rap had freer access, and an unlikely ally, as it reached young listeners in every corner of the country, Boyd says. Rap emerged from the Black community, and soon spread far and wide.

“Historically, there were barriers to the expression of some of those older genres of music,” he says. “In spite of that, they still found loyal White fan bases who would be influenced by that music. But it didn’t have the same sort of free form of expression and access that would be available for rap music by the 1980s.

“Which is why I talk about the role of MTV,” Boyd says. “Which, of course, originally was hostile in terms of playing Black music, but by the late ’80s, ‘Yo MTV Ra[ps,’ a hugely popular show, is what allows the music to spread throughout the country, whether or not the people listening to it had any direct connection to that experience or not.

“It didn’t matter,” he says. “Everybody was watching MTV whether you’re in an urban area, a suburban area, a rural area. If you had cable and you got MTV you could look at ‘Yo MTV Raps.’”

Rap music, like many genres before it, was a way for younger listeners to rebel against the tastes of their parents’ generation, he writes. Where early rock and roll saw White performers co-opt Black artists and find huge commercial success, rap was largely impervious to that kind of appropriation.

“When you get to rap music, so much of this is about lived experience,” Boyd says. “So as the music becomes more personal, a White person can’t come and claim that this is their own. They can listen to it and appreciate it and celebrate it. But it becomes kind of a minstrel show if you’re saying this is my life.”

A White rap star such as Eminem succeeded because he didn’t appropriate hip-hop culture as much as become part of it, something recognized by his early mentor Dr. Dre, which gave him credibility that a rapper like Vanilla Ice couldn’t touch.

“Eminem is the anti-Vanilla Ice,” Boyd says. “I think it speaks to just how things changed from, say, the time that Elvis was popular as someone appropriating Black music, and Eminem, who came along and said, ‘I want to be part of this culture. I want to be in it.’

“So when Jay-Z says we didn’t crossover, I think it’s important,” he says, referencing the line “I ain’t crossover I brought the suburbs to the hood’ in 1999’s “Come and Get Me.” “When you think about the ’80s, it’s the era of crossover, from Michael Jackson, Prince and Tina Turner. Whitney Houston.

“Hip-hop didn’t cross over. Instead, people outside the culture came to hip-hop.”

‘Evolution of the culture’

The latter chapters in “Rapper’s Deluxe” move through the ways in which rap and hip-hop sent deeper roots into every aspect of American and global culture.

The ’90s trace the rise of influence artists such as NWA, Jay-Z, Tupac Shakur, and the Notorious B.I.G., as well as chapters on offshoots of rap such as the Dirty South and trap music. It looks at artists such as Outkast and Three 6 Mafia – the latter of whom became the first rappers to win an Oscar – T.I. and Lil Wayne.

In the 2000s and 2010s, the book doesn’t focus so much on artists as impacts: the election of President Barack Obama, the shift of rappers into other businesses such as fashion and art, and finally, that landmark Super Bowl halftime show, produced for the NFL by Jay-Z’s entertainment company.

“I was not trying to write hip-hop’s greatest hits,” Boyd says. “I was not trying to write, ‘These are the new important rappers.’ Honestly, to me, once Obama gets elected? I mean, you want to talk about cultural influence? What is a better demonstration of hip-hop’s influence than the election of a president?”

In the final chapter, Boyd says he was more interested in spotlighting the unexpected ways in which rap and hip-hop has fully joined the larger culture.

“So, you know, the National Symphony with Nas performing ‘Illmatic,’” he says. “Or Kendrick Lamar winning a Pulitzer Prize. Or Swizz Beatz and Alicia Keys’ art collection, the Dean Collection. Jay-Z’s connection to Basquiat and more broadly contemporary art. “Rappers talking about their art collection the way they used to talk about their cars and their sneakers? To me that’s major.

“People can decide for themselves who the hot new artists are; we’ve covered that,” Boyd says. “That’s almost not as significant. What is significant, however, we can talk about hip-hop going into these previously elite White cultural spaces, and dominating in those spaces, because it speaks to the full evolution of the culture in ways that maybe pointing out who the hot new rapper is doesn’t address as significantly.”

Todd Boyd in conversation with Chuck D

What: Author Todd Boyd will be in conversation with Chuck D of Public Enemy, as well as signing his new book, “Rapper’s Deluxe: How Hip Hop Made The World.”

When: 7:30 p.m. Wednesday, Feb. 7

Where: Oculus Hall at The Broad, 221 S. Grand Ave., Los Angeles

How much: Tickets are with reservation.

For more: See Thebroad.org/events for information and to reserve tickets

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.