Getty Images/Michael Ochs Archives

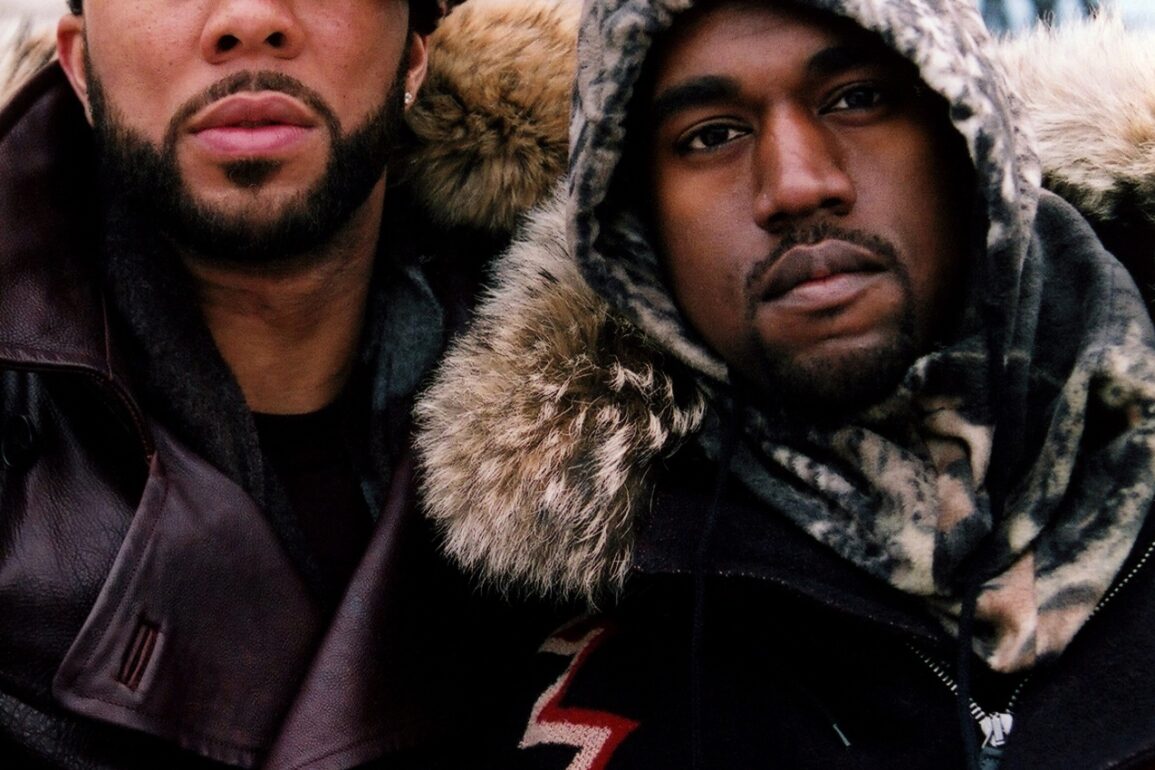

When Rolling Stone put Kanye West on its cover in early 2006, it set two undeniable truths on the table: how much the rapper-producer had already accomplished, and how thoroughly he recognized it. “The Passion of Kanye West,” whose David LaChappelle hero shot depicted the artist as a martyr in a crown of thorns, outlined the sea changes ushered in by West’s first few years on the scene, but also laid bare the maniacal focus of “the most provocative pop star in America,” a mercurial figure who spared no one — not even his senior and close collaborator, Common. A fellow Chicagoan and longtime friend whom Kanye had met while still in high school, Common was now the beneficiary of the younger rapper’s budding genius: The Kanye-produced album Be, released in May 2005, had resuscitated his career and secured four Grammy nominations in the process, trailing only Ye himself among rappers. Weeks before the ceremony, everything was looking up for their GOOD Music label imprint, which also boasted eight noms for soul man John Legend on its tally.

Yet if a rising tide lifts all boats, Kanye wasn’t satisfied with the current. He proclaimed that the Common song “They Say” — which featured the GOOD Music triumvirate and was nominated for best rap/sung collaboration — was far less deserving of an award than songs from his own sophomore LP, Late Registration. “You’re telling me that if someone sat you down in a room for 30 minutes and told you to come up with a list of all the best collaborations of the year, you would come up with ‘They Say’?” he asked Rolling Stone. “Not to sound arrogant, but how was ‘They Say’ nominated over ‘Heard ‘Em Say,’ and how was that song nominated over ‘Gold Digger‘?” Not so subtly, he was surfacing some friction between their perspectives, and expressing dissatisfaction that his taste was not reflected by the voting committee, with “Gold Digger” a shining symbol of his more boisterous, shameless and unpredictable hip-hop philosophy. They were of the same ilk — Chicago-bred interpreters of soul at odds with the influx of gangstas — but they were on different ethical and aesthetic wavelengths, with Kanye seeming to cast Be as a vestige of the past and Late Registration as a glimpse of the future. As it turned out, the Grammys agreed: Kanye went three for three in the rap categories, while Common left empty-handed.

But “They Say,” the penultimate song on Be, possessed its own prescience — a telling illustration of both rappers’ reactions to outside noise, and where those dispositions would take them over the next two decades. In its verses, you can find the quintessence of both MCs. For Ye: “Ah, the sweet taste of victory / Go ‘head and breathe it in like antihistamine / I know they sayin’, ‘Damn, Ye snapped with this beat!’ / F*** you expect? I’ve got a history.” For Common: “They say, ‘Dude think he righteous’ / I write just to free minds, from Stony to Rikers.” One is all self-importance, the other slightly self-conscious, and that simmering tension defines Be, a “woke” masterpiece and one of the greatest rap albums of the 2000s. The yin-yang dichotomy sustains their respective visions of home, a place as awe-inspiring as it is anxiety-inducing. Be is an album about being present, bearing witness, keeping your head on a swivel, gleaning insight. Learning was always a critical part of the Common mission, but here it is about listening, most of all to the streets, which bear the echoes and afterimages of all those who live and perish there.

On the album’s 20th anniversary, it’s much easier to recognize Be as a crucial intersection record — not simply for Common, on his way to becoming rap’s hokey, well-intentioned uncle, but for hip-hop decorum as an ideal, for neo-soul-inflected boho lyricism, for Midwest rap, and more specifically the hometown correspondent and hood ombudsman as fixtures on wax. But it is also a clear fork in the road, a moment of pure synergy paradoxically marking a widening ideological gap between the rapper and producer at the helm. Perfectly suited for its era, in hindsight it feels like a time capsule.

From the beginning, Common was pegged as a laureate running counter to gangsta rap domination. A Rap Pages feature from 1995 put the rapper-sage in league with “a new cavalry of MCs coming to rescue this damsel in distress known as hip-hop,” “urban poets [who] don’t need boasts of gat-spraying or pimp-slapping to do lyrical battle.” Common, for his part, embraced this characterization, in interviews and in song, though never so much that he saw himself occupying a world apart from the thugs he lectured. There could be a subtle condescension to his bars, but it was more the traditional superiority of an MC taking his word as law.

Be leaned even further into the tantric, Afrocentric revolutionary identity he had carved out for himself in the ’90s, landing in the wake of 2002’s Electric Circus, an admirably experimental, woefully flawed, extremely misunderstood album that flopped hard and alienated core fans. As Del F. Cowie, writing for Exclaim!, courteously put it in a hip-hop year in review for 2005 that slotted Be just ahead of Late Registration, “Critically savaged and a commercial failure, Common’s fifth album wasn’t as bad as it was made out to be.” One of the last albums recorded by the short-lived collective the Soulquarians at the famed Electric Lady Studios — on a run that produced instant classics like The Roots’ Things Fall Apart, D’Angelo’s Voodoo, Erykah Badu’s Mama’s Gun and Mos Def’s Black on Both Sides — its outré psych appeal was lost on a less forgiving hip-hop establishment. In response, Be enlisted Kanye, the newly ascendant Roc-A-Fella beatmaker turned backpacking solo star, as executive producer, with input from the Detroit loop guru and underground mainstay J Dilla, who had worked on Electric Circus as well as Common’s 2000 opus, Like Water for Chocolate. Both were practitioners of a sample-heavy, soul-forward sound that turned Common’s raps into homilies.

Common set his mandate at “writing freedom songs for real people” — those real people being the Windy City natives he’d observed throughout his life. “Black church services, murderers, Arabs servin’ burgers / As cats with gold permanents move they bags as herbalists,” he raps as if identifying landmarks. In many ways, Be plays like a newsstand for Chicago corner boys. He finds time for sex and spirituality, but foremost in his thoughts are the metropolis’s discounted hoi polloi: uncles that smoke and put blow up they nose; the cheater who couldn’t find peace at home; the man set up to take the fall in court; “Anointed hustlers in a fatherless region.” “Chicago nights, they stay on the mind / But I write many lives, they lay on these lines,” he explains in the intro. One of the key charms of the album is just how on the ground he feels, how watchful he sounds, recounting their tales with both a casual knowingness and a withdrawn authority.

Common has been blessed by so many gods of the drum machine that it can feel like providence, but there was clearly a flame drawing such producers to his work. Be is perhaps the purest demonstration of the rapper’s cornball charisma, and I mean that as high praise. His words are imbued with the acuity and prudence of a discerning old-timer, and he embodies the know-how and gumption of his original stage name, Common Sense. He could obviously conjure ricocheting phonetic feats (my favorite, from “The Corner“: “It’s hard to breathe nights, days are thief-like / The beasts roam the streets, the police is Greek-like”), but on songs like “Faithful” and “Testify,” he delivers simpler testimonials to his competence. Both display a curiosity, a desire to see things as they are and not as they seem; one is musing, the other urgent, but all of the verses are held together by their unassuming, down-to-earth neutrality. With Kanye backing him, saving hip-hop’s soul was the pitch, and it was working broadly, too — Be was Common’s first album to chart in the top 15 (it debuted at No. 2, bettered only in his discography by the follow-up, 2007’s Finding Forever).

If 2003’s “In da Club” by teflon New Yorker 50 Cent shifted rap’s locus, you can think of the rise of Kanye as a counterbalance. In 2005, the Shady / Aftermath / G-Unit conglomerate was dominating the charts (holding down half of the year’s 10 biggest rap debuts on the Billboard 200 and half of the top 10 rap songs on the Hot 100), but “consciousness” was gaining commercial momentum in response, and “backpack” rappers — socially aware samplers — were at the forefront of the movement. (Graduation triumphing over Curtis in a head-to-head sales showdown on Sept. 11, 2007, signaled an official changing of the guard.) Common was Kanye’s knight in the game, an old Chicago rap signifier newly restored as a stand-in for traditional hip-hop values. His sensual, John Mayer-featuring single “Go!” got spins on the radio. He appeared on the cover of XXL as part of Dave Chappelle’s “Hip-Hop All-Stars” with Kanye, and the second season of Chappelle’s Show featured the two Chicago MCs, Talib Kweli, Mos Def and CeeLo Green. The live version of “The Food” performed on the show appears on Be, as if to assert that the revolution would be televised. “Po’ livin’ in mo’ prisons, pointing to my mind, shine the light up / Clench my fists tight, holding the right up / Freedom fight in the dark gear for the years to get brighter,” he rapped, accepting the role.

There is, of course, a slight air of primacy on Be, the classic double-down of a rap classicist lamenting a gun-brandishing status quo. “I wonder if these wack n****s realize they wack / And they the reason that my people say they tired of rap,” Common grouses, taking his place in the never-ending debates over hip-hop propriety, professionalism and virtue. He’d earned, and welcomed, his reputation as a “conscious rapper,” though the term never really meant anything specific, and played into a perception as more enlightened than his peers. (To his credit, he did have the self-awareness to address the homophobia in his earlier work on Electric Circus.) Because Common was often made the moral standard bearer in a culture war, there was a sense that he was smug, didactic or a killjoy, rapping from a pedestal. But he wasn’t unapproachable — quite the opposite. Be has a real man-of-the-people, come-as you are energy: “Like juice and gin, in the city, we blend / Amongst the hustle, t***ies and skin, 50s and rims,” he raps on “The Food.” Though he would one day come to feel like a caricature of himself, this album is marked by the worldliness of its narrator, urbanity meeting inner-city familiarity. “The Chosen One, from the land of the frozen son,” he raps on the intro. “Explored the world to return to where my soul begun.”

The receptiveness of Be is rooted in Common’s beaming love for his hometown, as he and Kanye (and Dilla by proxy) plant a flag for the Midwest. “Chi-City” is the most obvious about it, striving to bring hip-hop culture back into his orbit by brute force, but “The Corner” and “Real People” are just as intent on marking out a regional sound and making the place a rap destination for good. Both build on Common’s early work with the producer No I.D. — who mentored Kanye — seeking to collapse the distance between the rapper’s jazzy 1992 sleeper Resurrection and the pop fireworks display that was The College Dropout. Ye and Dilla lived at opposite ends of that spectrum, but their beats for Be are on the same frequency: rich, sumptuous and expressive, with staggered drums that allow Common to strut through them as if sauntering all over his community. The beats speak as if reacting, and the songs don’t just utilize soulful vocal samples but are constructed around them: hanging in the background like chatter (“The Corner”), crying out dramatically (“Testify”), phasing in and out of focus like voices on the wind (“Love Is…“) or swelling into a devotional choir (“Faithful”), filling the air around him. The resulting panorama provides a gapless immersion into the Chicago of Common’s memory and imagination.

Even with this symbiosis, the Dilla beats are noticeably the sunnier ones, whose warm light finds the MC at his most optimistic. “Love Is…” seeks a more nurturing hood and tugs at the shackles of masculinity (“If love is a place, I’ma go again”), but it’s the eight-minute closer, “It’s Your World (Part 1 & 2),” that really locates his thesis of pure belief. After verses reliving the world he’s known, he envisions the world of his dreams, punctuated by a gaggle of children rattling off all the things they want to be when they grow up. The album is brought to a resounding conclusion by Common’s pops, Lonnie Lynn Jr., who lists states of being like affirmations. “Be the resident of that 12th house,” he says. “Be … eternal.” It is here that Common’s positivity gospel spirals into the future.

Kanye used the outtake beats Common passed on for Be to build out Late Registration, released late that summer. That album eschewed Common’s brand of noble idealism, and from that point on Kanye was relentlessly moving away from both soul and cultural awareness. Be feels like the last moment where the “conscious” and “backpacker” paradigms overlapped. Common and Kanye would work together again, but they were on different trajectories, the former dependable to the point of stagnation, the latter a chaos being hurtling toward maximum nonconformity. As the world elevated Kanye to superstardom, his interpretation won out. The shift started in their own city with Lupe Fiasco, carried into the 2010s with Chance the Rapper and the MCs of the YOUmedia circuit, and fanned out in all directions — Drake and Kendrick, Kid Cudi and Travis Scott, J. Cole and Tyler, the Creator. Quickly, the music Common trafficked in, which best reflects the respectability politics that accompany the “conscious” label, sounded somewhat toothless next to fierier polemics like “Crack Music” or “American Terrorist” or “Paranoia.” Unchecked optimism can become naivete; his worldview in the years to come is arguably better captured by the quixotic and banal soapbox record Let Love than the insurgent politic of 2016’s Black America Again.

Common likely didn’t realize the future he’d envisioned into being, and he lost the grander holy war for the “conscious” rapper’s place in pop culture — but looking around the present day, there have been moral victories. The glow of his hopeful lyricism can still be felt, even in his hometown. Dilla has never been more revered. There is a clear line to be drawn from the run of Common albums that ends with Be directly to this year’s From the Private Collection…, a collaboration between No I.D. and the Chicago rapper Saba. Common doesn’t really embody the Be ethos anymore, and Kanye has fallen far off the righteous path, but Be remains a Rosetta Stone for a form beloved by hip-hop diehards, and Common was the right professorial character at the right time to deliver the edict.

“It’s tempting to think that records like Common’s Be and Kanye West’s The College Dropout represent a trend towards hip-hop that can be hugely successful without pimping cartoons of trigger-happy thugs and sex fiends,” Will Hermes said in a 2005 review of Be for All Things Considered, unable to hide his exhaustion with the prevailing landscape. Many felt as he did, that the two personified a “strong moral conscience” missing from hip-hop. Careful what you wish for: Kanye did remake rap in his image, but at a cost. It was always misguided, always an oversimplification, to dismiss the potential ills within “conscious” rap for the sake of embracing a more puritanical value system. In recent years, Kanye has emerged as a raving rage-baiter, spewing antisimetic nonsense amid the diminishing returns of his albums; that artistic decline has made him easier to finally dismiss, but his worst impulses were always lingering under the surface. Many of us ignored them when they seemed more innocuous, platforming him on the basis of a subversive creative ethic that gradually became a slippery slope. Listeners espousing that ethic are ultimately implicated in creating the uncontrollable megalomaniac we see today, whose defiance is self-serving. It began with treating him like a genius who could do no wrong.

Here’s what they say about Kanye and Common now: that the former is disgruntled and delusional, sustained by his edgelord cult and an increasingly desensitized public that can’t look away from his car-crash antics; and that the latter is frozen in carbonite, a benign if performatively ritualistic presence, always hovering around the best rap album Grammy shortlist, most recently for a profoundly conventional throwback LP from last year. There are insinuations of those futures back there in 2005. But now, more than ever, the album they made together feels reminiscent of a simpler time. For a moment, the two rappers were all potential energy, chasing a tomorrow full of promise. They could just be.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.