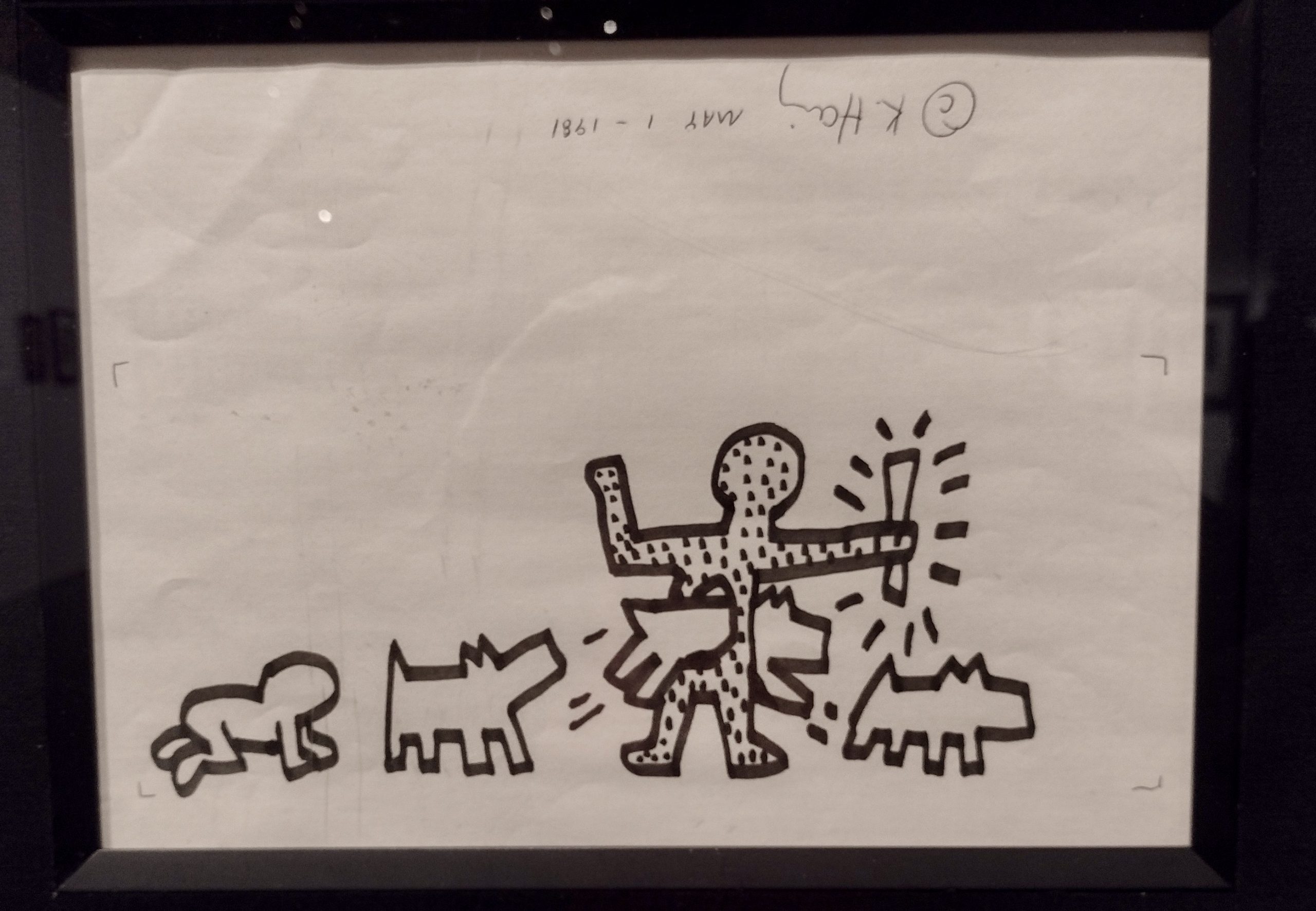

Keith Haring (untitled) man dog lithograph, 1982. Offset lithograph, 9 × 9 in | 22.9 × 22.9 cm. (Photo: Gillian Gaar)

It’s Saturday night, and people are partying like it’s 1985.

It’s the opening night of the exhibition “Keith Haring: A Radiant Legacy” at Seattle’s Museum of Pop Culture (MoPOP), and the evening is dedicated to conjuring up a little of that East Village spirit. Drag queens are lip-syncing to Madonna. DJs keep the beat pumping between sets; Blondie, Beastie Boys, Cyndi Lauper. A few brave attendees careen unsteadily around the dance floor on roller skates, like modern-day Rollerenas (a self-proclaimed “fairy godmother” of the 1970s and 1980s who haunted the Village by day and trendy clubs like Studio 54 by night). A retro photo op has been set up: a pay phone hanging on a heavily graffitied wall (in a bit of irony, the resulting photos are texted to your cell phone). All of it reflects Haring’s own colorful, playful style, celebrating the exuberance of the decade when he rose to prominence.

“A Radiant Legacy” is a remarkably comprehensive exhibit, tracing Keith Haring’s fast-paced journey from subway graffiti master to an artist of international acclaim. There’s a copy of his school yearbook, showing Haring as a geeky teen. There are pieces from his own art collection, establishing his interest in supporting fellow artists. There’s a selection of goods from his store, the Pop Shop, his democratizing attempt to move artworks out of elitist circles; maybe you couldn’t afford a first edition print of “Radiant Baby,” but you could always swing by the Pop Shop and pick up a button with the image at a more budget-friendly price.

WHAT: Keith Haring: A Radiant Legacy

WHEN: Open now through March 23, 2025

WHERE: Museum of Pop Culture (MoPOP), 325 5th Ave N, Seattle, WA

Overall, what you get most from the show is a sense of joy. The stick figures that are Haring’s trademark are always in perpetual motion, creating a celebratory mood despite the fact that the figures have no facial features. Even when they’re in a more serious setting — the AIDS awareness “Silence = Death” imagery, for example — they exude a fierce defiance. Ever upbeat, never downtrodden.

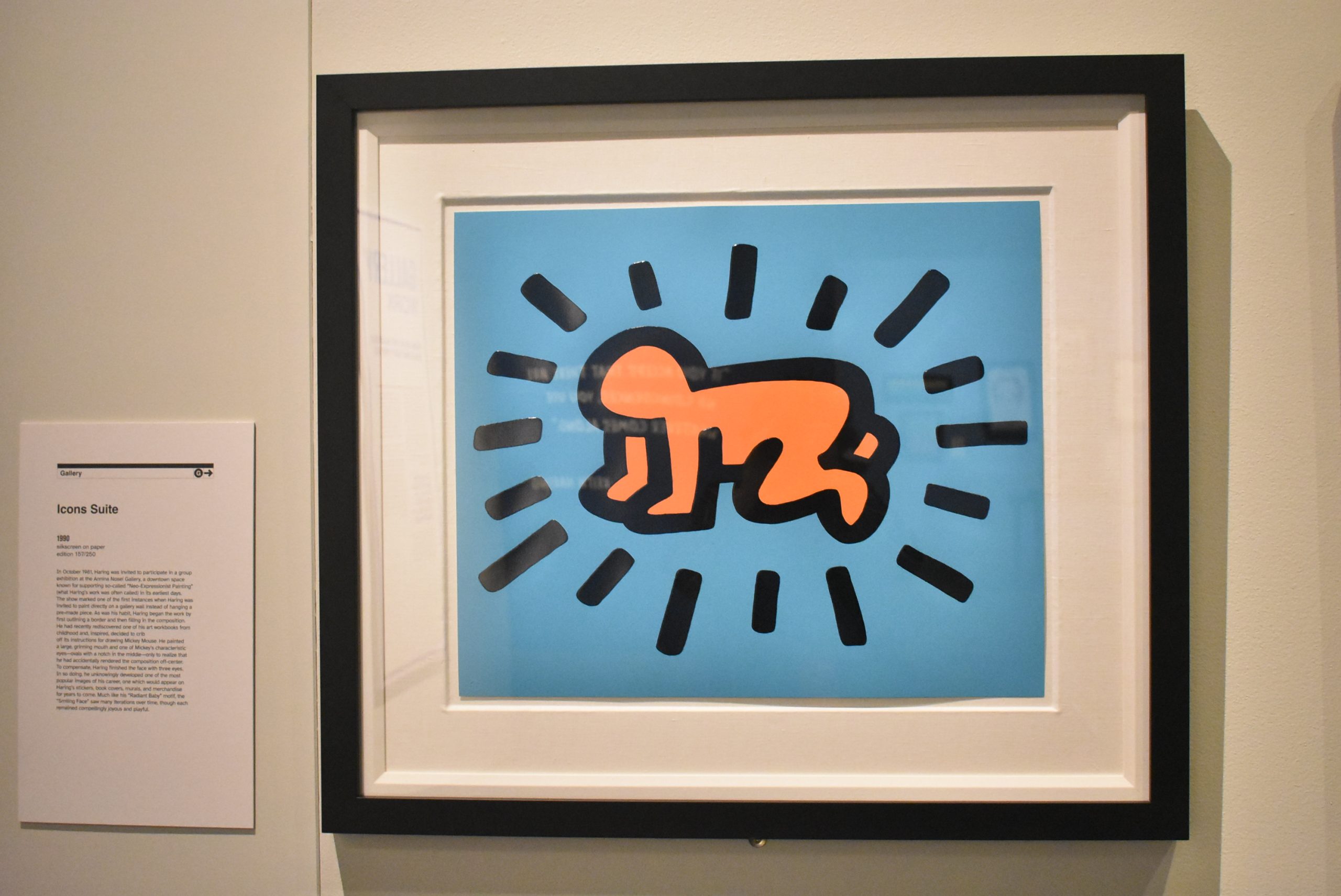

Radiant Baby (from the Icons Suite series), 1990. Silkscreen in colors with embossing. 21 × 25 in | 53.3 × 63.5 cm. (Photo: Gillian Gaar)

Haring moved to New York City in 1978, the year he turned 20. He’d grown up in Kutztown, Pennsylvania, and studied at Pittsburgh’s Ivy School of Professional Art; in his new environment, he quickly found a place in the burgeoning underground graffiti/street art culture that future talents like Jean-Michel Basquiat also sprang from. He’d noted how old ads in the subway were covered with black paper before new ads went up and adopted these blank spaces as his first, improvised canvases. Some of this early work survives and is seen in the exhibit: sheets of black paper, torn at the edges, with the faint markings of the stick figures that would soon become familiar. It was during this period that he created the “Radiant Baby” image; the outline of a crawling child exuding beams of energy. Haring used the image as a tag in his street art.

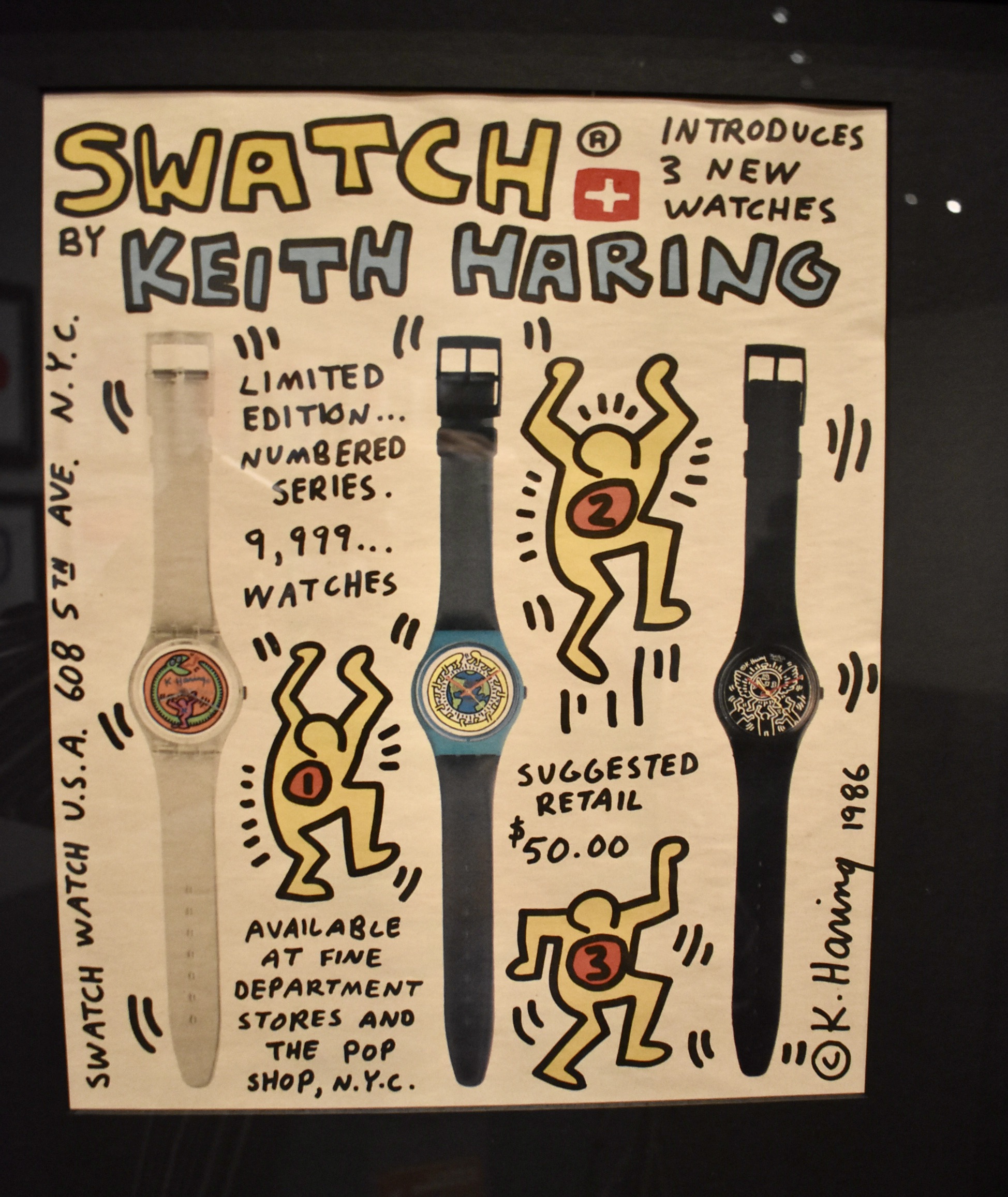

Keith Haring, Swatch. (Photo: Gillian Gaar)

In a resume from 1981, Haring charted the steady progress of his career, the range of group exhibitions he’d participated in, and his two solo exhibitions (at New York’s Westbeth Painters Space and Club 57). Within a few years, his work was being exhibited worldwide, and by mid-decade, Haring had become a cultural phenomenon. The Pop Shop opened, bringing his art to the masses on buttons and t-shirts. He spoofed his own commodification by turning himself into a “product” in a photo session with Annie Leibowitz, stripping naked and painting his body to match his own stick figure style.

In addition to his work, he also did commissioned projects, like album covers, ads for Swatch watches, and Honda cars. But what really defined his character was his increasing involvement with social justice issues. He became an AIDS activist, and you couldn’t visit New York in the 1980s without seeing a Haring-created design based around the ACT UP slogan “Silence Equals Death.” South Africa’s struggle toward independence was also a hot topic at the time, and Haring summed up the conflict in simple, striking imagery over two panels: a large black figure held captive by a noose that’s held by a smaller white figure, the black figure ultimately winning the battle by crushing the white figure underfoot.

Keith Haring, “Luna Luna Karussell.” (Photo: Gillian Gaar)

But most of the show focuses on positivity. Haring’s model of a carousel designed for Austrian artist André Heller’s Luna Luna Park (an amusement park where the attractions were all designed by artists) is charming, as are the accompanying murals, full of brightly colored figures dancing or flying (there’s also a bizarre half man/half chicken creature on the carousel). A 1981 ink drawing features early versions of two of his best-known images, “Radiant Baby” and “Barking Dog,” both later to become centerpieces of his “Icons Suite.” As presented in “Icons,” both “Radiant Baby” and “Barking Dog” are stark in their simplicity; each piece makes use of only three colors, for example. But there’s a vibrancy about them that conveys a positive energy. That barking dog isn’t angry; it only wants to play; it’s an element of Haring’s art that makes it immediately engaging.

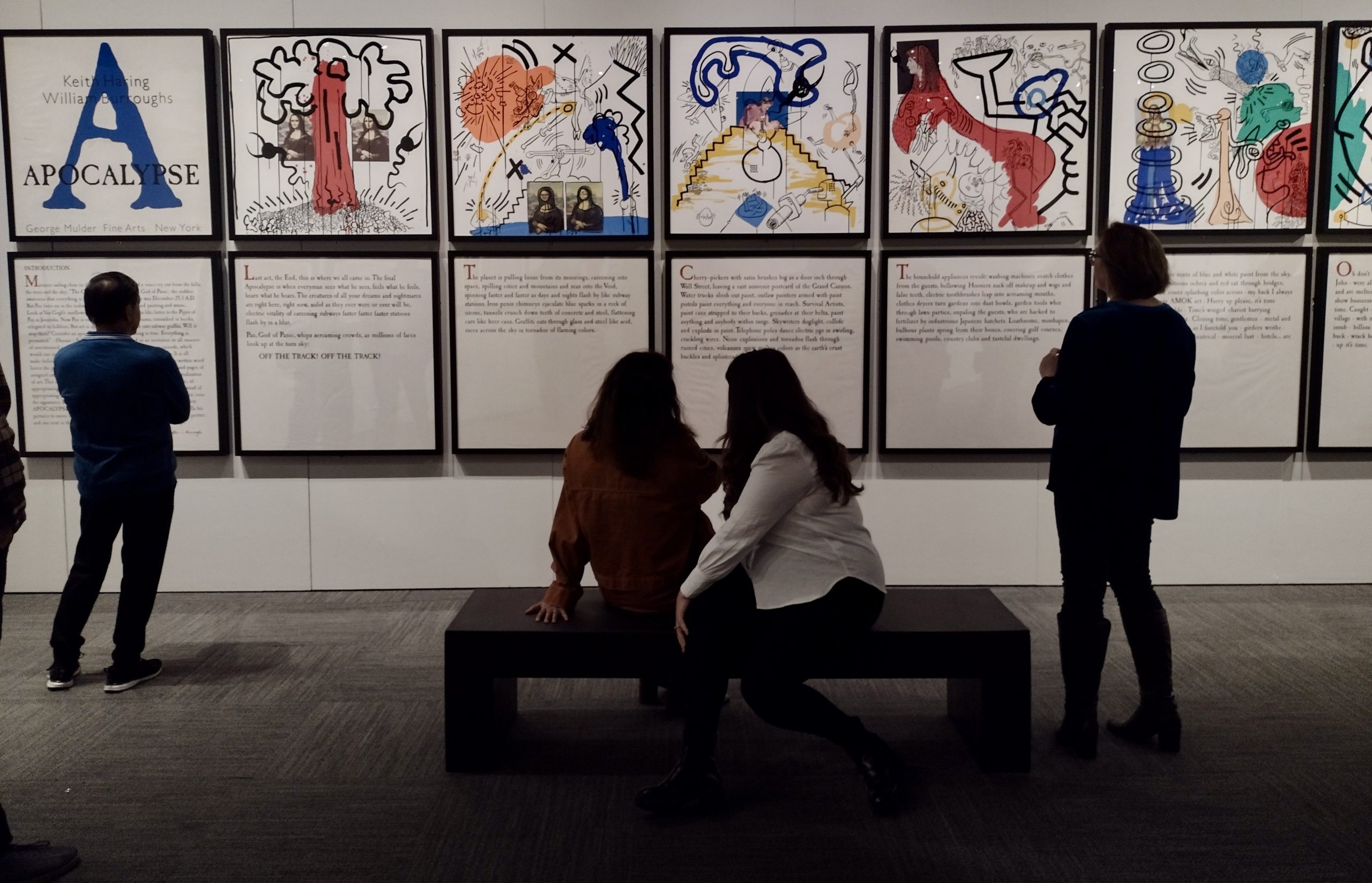

“Keith Haring: A Radiant Legacy,” MoPOP Exhibition View. (Photo: Gillian Gaar)

There’s also space devoted to Haring’s collaborations with others, including Angel Ortiz (LAII), a series of etchings with an elementary school boy named Sean Kalish, and the stunning “Apocalypse” series, created with William Burroughs. “A Radiant Legacy” emphasizes what a compulsively prolific artist Haring was, a mercurial figure who moved with ease between the realms of fine art and Madison Avenue advertising. He also constantly sought out new avenues for his work and, not feeling threatened by his fellow artists, was eager to collaborate with them (he’d met Kalish because he was a frequent visitor to the Pop Shop). Most of all, he wanted to create work that inspired. And you get the sense that if someone’s response to seeing one of Haring’s pieces was to create art themselves, he’d be absolutely delighted.

Haring’s busy career came to an end when he died of AIDS-related causes in February 1990. It was less than two years since his friend Jean-Michel Basquiat’s death in 1988. At the time, Haring had written of Basquiat in Vogue: “He truly created a lifetime of works in ten years. Greedily, we wonder what else he might have created, what masterpieces we have been cheated out of by his death, but the fact is that he has created enough work to intrigue generations to come.” The same could be said of Keith Haring’s own work. And, “A Radiant Legacy” offers a deep dive into the creativity of one of the most remarkable artists of the 1980s.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.