Talking of all that, your era are our cultural progenitors. Our era of graffiti was a cocktail of good drum’n’bass, bad skunk and ugly state harassment; we are the ASBO generation. And, in turn, you lot were birthed by all that ’80s New York b‑boy stuff.

I’ve slightly overlooked that part of it. I like how culturally important we are to you, 10Foot, and how your generation has really gone out raving. The idea that the energy of this music, socially, has all of the soundscape. Which is so UK.

That’s what graffiti was like for me: a coming together of classes and of races and of every- one. It was a fucking problem for the system. The way I saw graffiti, the way I grew up on it, it’s standard to do arrows and squiggles and stars and shit. And as I get older, I feel like what’s essential is purifying your own vision of what you’re doing. I’ve pared it back now. A lot of people don’t see this, but there’s a lot of thinking in the simplicity. For you, I wondered if there was a process of trying to unlearn the Americanisation that culturalised you?

There is and I’ll tell you what it is. I’ve always been hip-hop through and through. I’ve always been a b‑boy. However, when hip-hop started becoming really commercialised, I realised that within my own culture I must thrive [alongside] these different people [and UK independent labels] who were coming through.

I realised that I would have to then stop painting physically… And that the only way that I could survive this, was to be able to do this within the music. We are the wildstyle of this music. We are the sonic terrorists, if you like.

Isn’t it strange that the scientists have now worked out how to make fucking fuel out of waste products? Well, that’s exactly what we’ve had to do, from a mental point of view, a very, very long time ago: make something from nothing. It’s like DJing, for me. When I go and play music now, it’s like I’m going to a library that’s quite extensive, and I’m going to shuffle through all these great books, and I’m going to lay them down in a conversation with each other. And for you, 10Foot, you’re now [similarly] learning the art of simple complexity.

Yeah, man. You have to steal a plan of the prison, find a teaspoon, then spend a long time digging for freedom. What motivates you to keep on being a provocateur, a radical?

There is much to do. Let’s get to the point: are we going to change anything? Do we need to change the government’s ways and views? I think the back-pocket- ing that they’re taking right now, it’s become this banking system. My personal beef is, the minute that you took the school from the middle of my community where I lived, and you ripped out the primary school, and you threw it away with government [cuts] and the estate imploded, then my son became a murderer. [In 2010, Goldie’s son Jamie, then 23, was sentenced to life imprisonment, with a minimum of 21 years after he was convicted of stabbing to death a rival gang member in Wolverhampton.] His cousins and all of his relatives became the same. And I couldn’t save him. All the fathering in the world couldn’t save him.

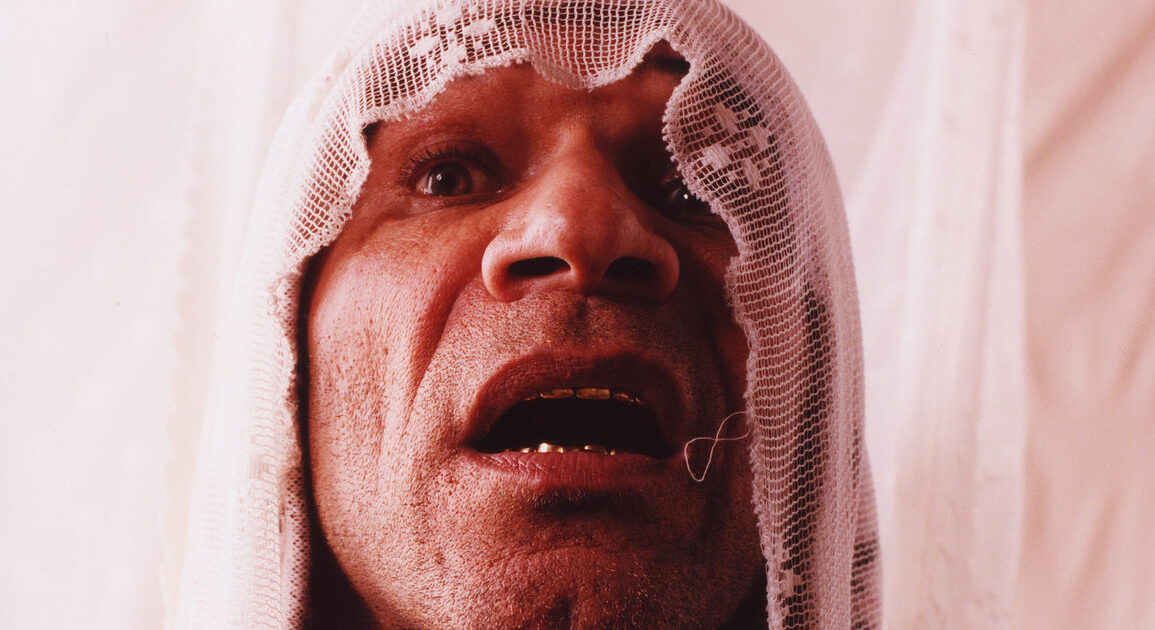

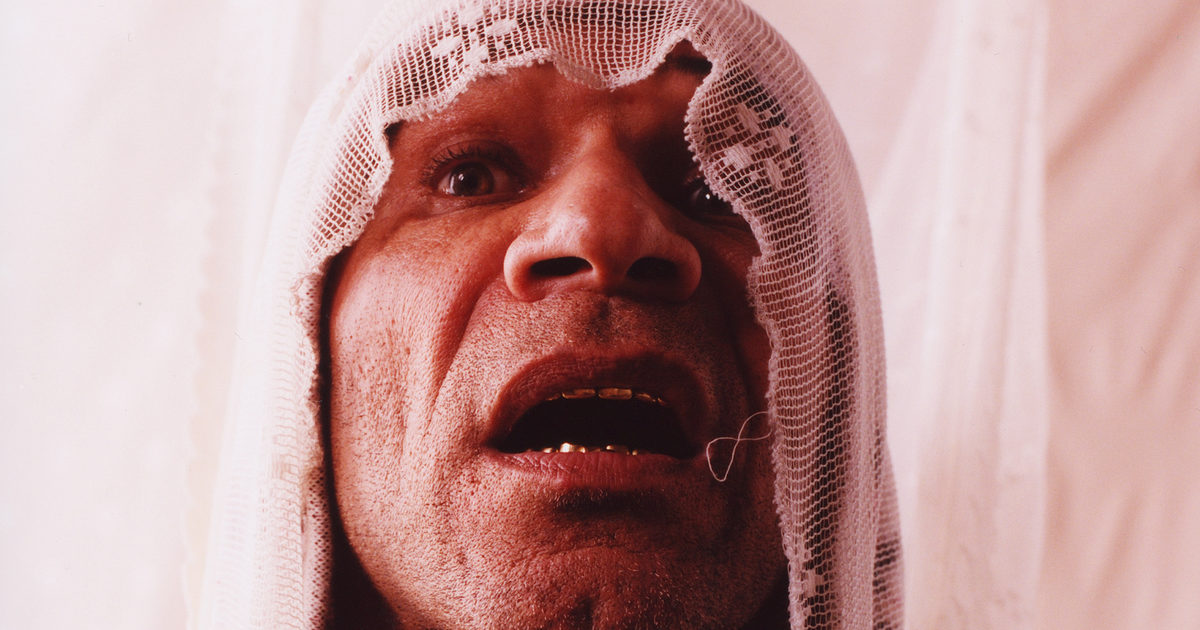

The one thing that I can’t take away is being a product of being in care all my life. And I’ll say this open-heartedly: “Thank fuck, mum, you put me away. Thank God you put me into care.” Because I spent years learning what this name, Clifford Price, meant; what it meant to have it sewn into my clothes every day. [It meant] I wanted to create a character named Goldie because I wanted to become a superhero. I wanted to become something different than everything you’ve ever labelled me for. And breaking that down by saying to them: “Fuck you!” Because I’ve made this on my own. I paid my fucking taxes. I paid my fucking dues.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.