Walk by the colorful Blackwell Drip Mural on Hull Street this Saturday night and you may begin to feel like the walls are breathing. Don’t worry, nobody spiked your drink.

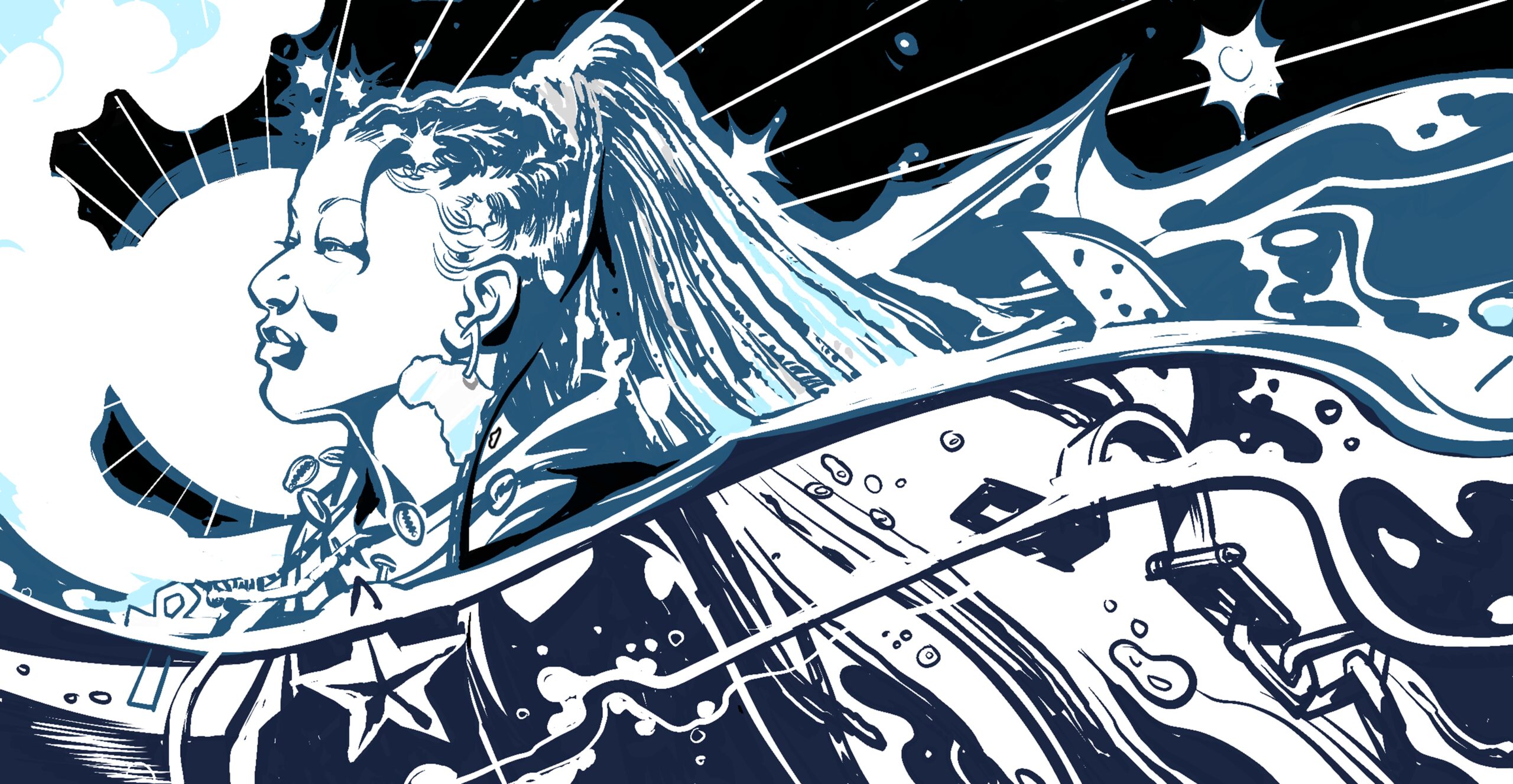

Instead you’ll be witnessing Flow, an immersive, one-night-only event centered around this public mural created by artists Heide Trepanier and Chris Visions, who combined imagery of Yemaya, an Orisha queen from the shores of Africa, with the visage of Richmond hip-hop artist, Cole Hicks (formerly Lil Nikki from South Side).

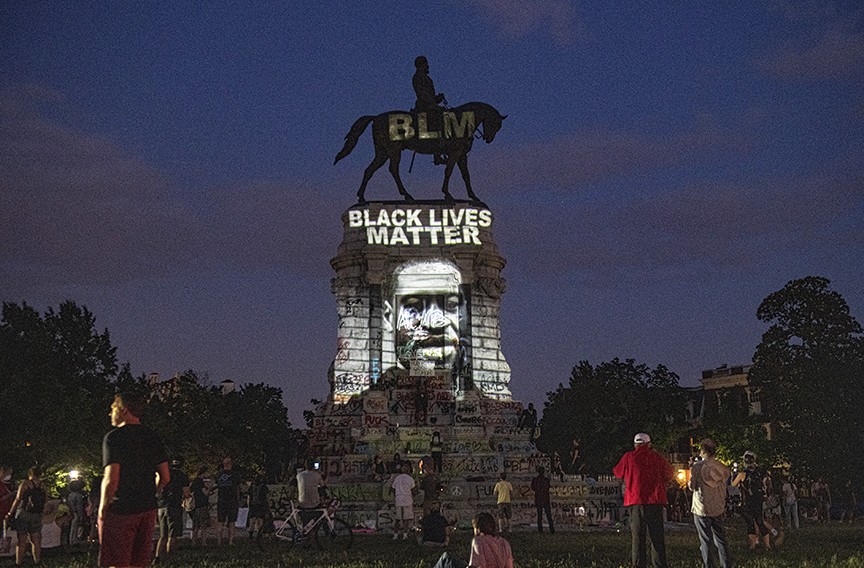

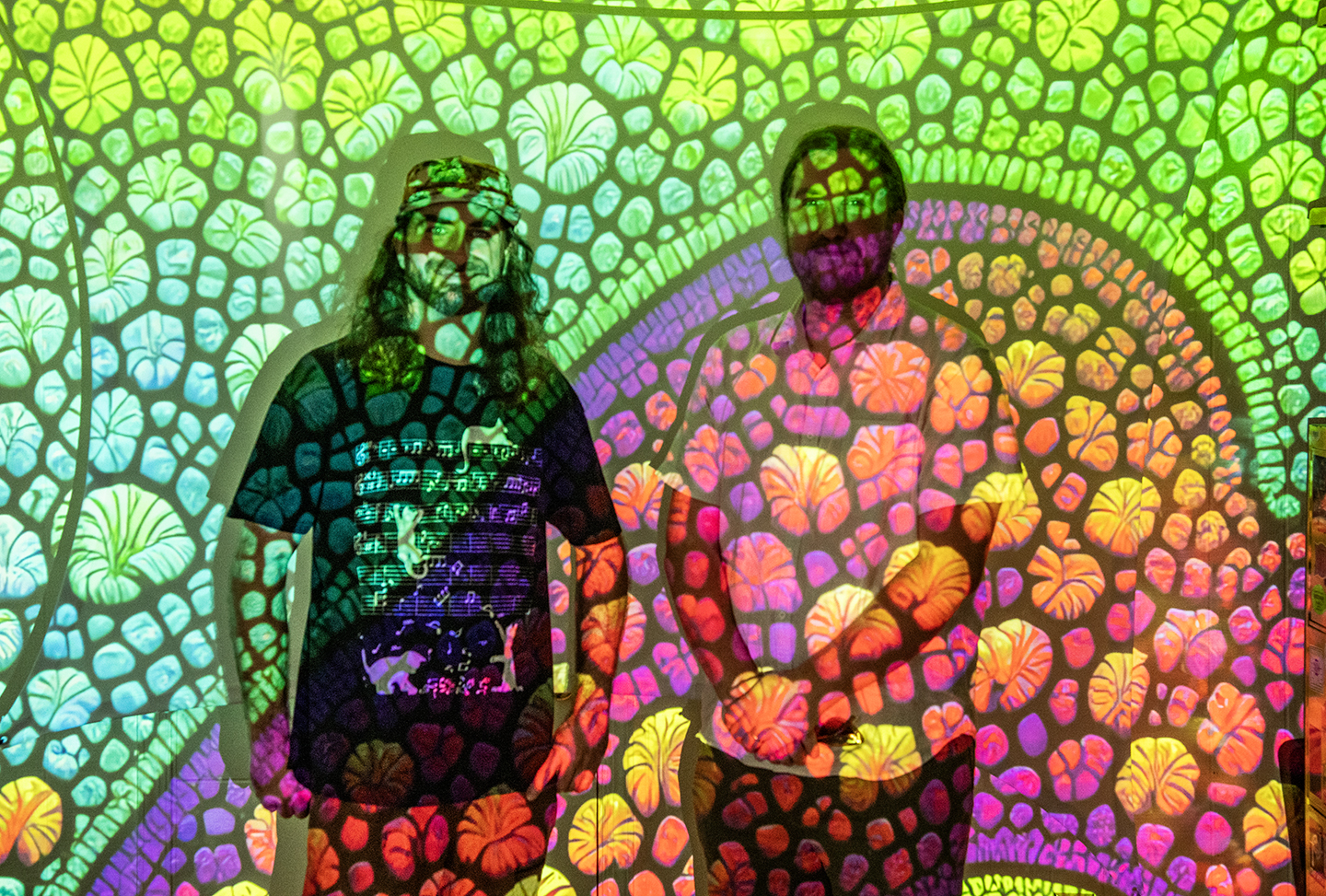

The mural will appear like it’s alive thanks to animation and project mapping by Collaborative Arts, the nonprofit founded by 38-year-olds Alex Criqui and Dustin Klein, the guys behind those famous projections on the former Robert E. Lee Confederate Monument during the protests over the police murder of George Floyd in 2020. Known as Reclaiming the Monument, that project was part of the reason The New York Times called the transformed statue “the most influential work of protest art since World War II.”

For this weekend’s event, Collaborative Arts is partnering with Mending Walls RVA; both organizations are dedicated to fostering public art and community engagement in Richmond. Local graffiti artist Silly Genius also designed a coloring book page that anyone can download, fill in and submit before the event, with submissions being transformed into a community montage to be projected onto an opposite wall during the event, which will take place at 1621 Hull St. from 6 p.m. to 10 p.m. on Saturday, April 12.

Last week, we caught up with Criqui and Klein to hear what they’ve been up to since we last covered them a few years ago. The interview was lightly edited for length and clarity.

Style Weekly: Fill us in on how things have been going the last few years?

Alex Criqui: Well, in 2022, we got a big grant from the Mellon Foundation and were able to do a series of collaborative installations with different institutions and artists, community groups like the Pamunkey Indian Museum and Cultural Center and The Valentine. We also collaborated with artists like graffiti artist Silly Genius, Sandy Williams IV … through 2023, when we decided we wanted to keep doing this. So we founded our own nonprofit called Collaborative Arts.

We’ve been really fortunate. Last spring, we got a [$500,000] private grant from the Weissberg Foundation, which is located in [Arlington] Virginia. And we spent the last year figuring out how to best use the five years of operational funding to continue our mission: To use public art and light-based art for advocacy, and to support public artists in Richmond and help them achieve big visions, as an artist-led nonprofit.

We’re putting $200,000 of that grant toward public art projects over the next five years, and hoping to grow from there. Right now, we’re exploring options on how to use it the most sustainable way. With our other grant funding, it came and went real fast. We’re trying to explore how we can potentially work with the city to use public spaces and public infrastructure to create longer term public art installations—whether that’s permanent projections, other light-based artwork, murals. All City Art Club is our main partner [he says they are in early conversations for a public art installation in at least one downtown location, but could not comment on it yet].

Are you getting any federal grant money that might be impacted by the current administration’s agenda? Or has that affected groups that you work with?

Alex Criqui: Partners might be affected who got NEH grants, that’s a big concern. Luckily right now, our funding has been through those two private foundations. But it definitely limits our options, and I know there has been some talk about limiting speech advocacy for nonprofits … or revoking nonprofit status if you do things this administration does not like. So far, it hasn’t directly affected us.

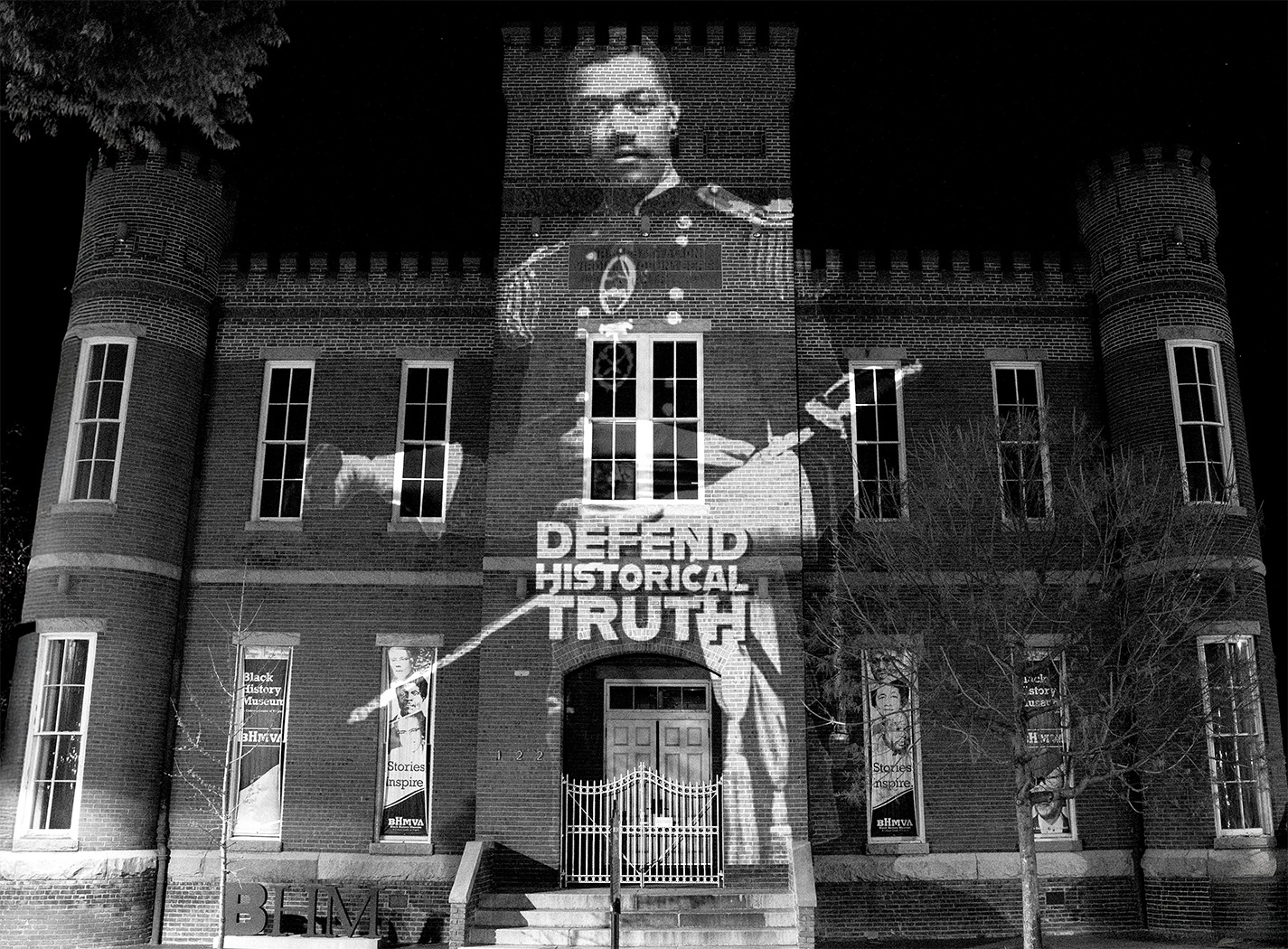

There was a lot of interest online for your recent projections on the Black History Museum and Cultural Center on April 2 [images were projected in celebration of Richmond’s 160th Emancipation Day to honor the African American soldiers who served and passed through Leigh Street Armory]. What was that like?

Alex Criqui: I think the great thing about that project with the Black History Museum is that it felt like the first opportunity to respond to what’s happening on a national scale in a way that’s not just adding to the noise, but is uplifting for the community and affirming our values as a community.

It was last minute but it was great; we had 50-60 people come out to support the museum and the history of the Jackson Ward area and Black Richmonders, and particularly the people who dedicated themselves to national service and community service in that building. That felt like the first really positive outlet for us.

We’re always trying to approach this by addressing negative things in a positive way, not so much just a back-and-forth diatribe … I think people all over the country are not happy about the brutality and attacks on institutions in [their] community, and they’re looking for positive ways to respond and not just create more noise.

Explain the difference between the different groups you’re associated with, such as Videometry and Collaborative Arts?

Alex Criqui: Collaborative Arts is the nonprofit, I’m the executive director of it and Dustin is the technical director, but we also have a board that includes [artist] Miguel Carter-Fisher, who is a teacher at VCU, and Stephanie Merlo, a longtime local activist, veteran [and LGBTQ advocate], and artist Silly Genius of All City Art Club. We’re really hoping for it to serve our work and the work of other artists in the city, so we can support good causes and build community infrastructure through art.

Dustin Klein: Videometry [Visuals] is my lighting design company that I’ve had for a long time [it also includes his concert touring work].

Do you still use the Reclaiming the Monument name?

Criqui: Yeah, so Reclaiming the Monument is like an art project, while Collaborative Arts is the nonprofit entity that is here to fund different art projects and artists. In the past, we’ve had to get fiscal sponsorship from other nonprofit entities, but now ourselves, and other artists we work with, won’t have to go find a fiscal sponsor who maybe isn’t focused on the same areas. Our goal is to keep the overall structure [of the nonprofit] in the hands of artists, so we can help them pursue what they want to pursue.

Reclaiming the Monument is still more for that specific strain of social commentary and mindful language. Collaborative Arts can be for larger projects; it actually started with a great blacktop mural skating rink at Hotchkiss Community Center [North Side] in 2023, with Silly Genius and All City Arts Club. That was through our Collaborative Art grant program that we created, and that sort of grew to become the nonprofit because we saw the power of helping to get resources into the hands of artists—and all the amazing opportunity that created.

How has it been working with the city?

Criqui: So far, we’ve been working with the Public Art Coordinator, Monica Kinsey, trying to see how we can build these partnerships. And with [City Council Vice President] Katherine Jordan, who has been a huge help. We’re talking to City Council trying to get everyone’s ear about how we can take resources we have in hand, and those we’re working on gathering, and make a long-term impact for the city. If you look at other cities throughout the country and the world, they have greater cooperation between city government and arts organizations, which leads to a really robust public art landscape.

We’re making a cultural and economic argument for why this is in the long-term interest of city to use public space to create places of permanence for long-term public art investment. A lot of times, you work really hard for years to get funding, you implement it, and maybe you work with a business which is sold, then all your work for is gone. So, the city has a unique position to offer places of permanence and help facilitate. The arguments for the impact are borne out by many other localities; they might be bringing in $125 million a year for an immersive art festival; or like in Osaka, Japan they work on this immersive art space Teamlab, which turns a public park into a nightly art installation and that has 3 million visitors a year. There’s a lot of compelling statistics and data that drive tourism and offer reasons why Richmond shouldn’t just call itself an art city [it should be one] …

To your point, a recent popular mural on Broad Street (“Greetings from Richmond”) was removed which brought up the issue of murals from historic periods being temporary in nature; nobody will be taking their kids to see them. Is that one of the reasons you guys are attracted to light-based art, the ease with which it can be recreated or transferred?

Klein: I think murals generally are temporary. We can use light to fill spaces when its dark, and it’s a great tool to get art out before people’s eyes quickly and easily. But we can’t do anything during the daytime and people need art then, too.

It’s a big issue in the city that we’ve been talking about a lot with artists, how to preserve street art. Richmond wants to hold itself up as a street art city, but how can it best preserve street art, keep creating more public art in the city, inviting more artists to live here, and making it a positive place for people and artists to be? That’s a big mission in terms of how we can work with the city and everyone around us to try to help preserve those spaces and make them better wherever we can …

Criqui: Our five-year mission is to build coalitions across arts organizations and cut the red tape. I’m sure you know that a few years ago, the fund the city earmarks for public art was basically raided for other use. We’re trying to say, “Hey, put this money in the hands of artists.” Because when I see promotional material for the city, they use some of our art, and other artists’ art, but a lot of it is not stuff that was actually funded by the city.

Have either of you heard anything more on any plans for any public art on Monument Avenue?

Criqui: No, well we tried before the landscaping was put in [at Marcus-David Peters Circle, formerly the site of Robert E. Lee statue on Monument Avenue). With the Mellon Foundation money, we funded a community garden sculptural artwork by Virginia artists Larissa Rogers and Luis Vasquez La Roche, super-talented artists who made this really beautiful garden bed called ‘Operations of Care’ [now at Visible Records in Charlottesville].

The idea was to invite people to come heal the land through tending the earth, tending the garden … But a decision was made by the Richmond Planning Commission without a public hearing. I think there’s resistance to letting the energy that was there in 2020 come back to Monument Avenue. And more broadly, in terms of public art and the voices I’ve heard, a lot of people on the artistic side and grassroots side don’t want to focus on reinvesting in a wealthy neighborhood that, by and large, already has a lot of disproportionate advantages in terms of investment. I think public art should be spread out, put in South Side, North Side and East End, throughout our community instead of focusing on one historically racist street.

Has all of the Mellon Foundation money been spent?

Criqui: Yeah, that’s been spent, I think the Monument project is on hold. That said, they have invested a lot in Richmond, they put a lot of money into the Shockoe Bottom slavery museum project [Shockoe Institute] and the JXN Project’s Skipwith-Roper House [Jackson Ward’s first known Black homeowner, Abraham Peyton Skipwith at 303 E. Bates St.].

What can you tell us about the Flow mural project this Saturday night (April 12) on Hull Street? Also how often will you be doing these projection installations moving forward?

Klein: We’re definitely trying to get them happening more often, but the April 12 one is the only one we currently have on the books. This Saturday is a collaboration with Mending Walls, who created the mural [with the artists]. We mapped the mural and wanted to give people the opportunity to come see it [animated]; and we added other elements to the night, like the digital community mural and art wall.

In doing all the research on [our] nonprofit, we found all these fascinating, awesome facts about how contributing and participating with public art is super good for the mental health of communities and the people who participate. We’re doing this coloring book project with Silly Genius, who created these outlines of the word Blackwell; we put them in Studio Two Three, and have them at Visual Arts Center. People can also download them from our website and fill them in. We’re going to create animation of all the artwork so people can see their art on the wall, projected together.

[We’re also animating] the Blackwell Drip mural by Heide Trepanier and Chris Visions, which is this beautiful mural that’s a tribute to Cole Hicks, Richmond rapper and writer. Flow is just an open, free event where people can come make some art, listen to music, and just have a good time.

“When you look at [a mural], even still things have motion that’s intended. So just trying to bring out that intended motion and go with those themes that support that and make it what it is—that really helps the animation bring it to life.”—Dustin Klein

How long does it take to put one of these projects together, Dustin, because you’re on the road a lot with a band, correct?

Klein: Yeah, I’ve been touring with this band Papadosio for the last eight years, but we’re actually going to be taking a year or two break next year. So, I’m getting myself ready to come off the road a little bit. I’ll have a little more time in the future to do some of these projects, and I’m trying to build some more things around Richmond as I scale back from [touring]. Each project takes a variety amount of time, depending on what the project is. But I’ve been doing productions for a really long time now, which helps speed things up, knowing all those techniques and that knowledge …

Artistically speaking, when you create one of these animated murals, what makes it successful to you?

Klein: You know, one of the cool things is they’re all so different. When you look at it, even still things have motion that’s intended. So just trying to bring out that intended motion and go with those themes that support that and make it what it is—that really helps the animation bring it to life. For example, with this upcoming piece [Blackwell Drip mural] being able to bring real ocean water, waves and wind, or natural elements, can really help the artwork breathe and bring a different experience [for the viewer] also seamless loops … Richmond is really fortunate to be full of a lot of awesome, beautiful murals. And there’s so much potential to use light to activate more of those spaces, and so many different kinds of events can be done around these projections.

A lot of these murals really aren’t well lit at night, which is disappointing to me a lot of times, when I walk around and see that kind of thing [laughs]. I’m like, “Damn, there’s not even a light on this one.” … We have so much history in Richmond, too, it’s powerful to see how inspiring it is for people to see these historical [black-and-white] photos blown up like at the Black History Museum. There’s a lot of opportunity to illuminate parts of the city that would be left in the dark otherwise.

What’s the biggest challenge your nonprofit faces?

Criqui: It’s definitely access to public space. We’ve had several projects with the city now, and they’ve been great. But in terms of what we can do, we’d like to see more action than talk. We’re at the beginning stages of this conversation with the city, as the new mayoral administration finds its footing and everybody reprioritizes the plan going forward. It’s a process, but we definitely feel like there’s renewed energy, and especially Katherine Jordan has been super helpful. We’re optimistic that Mayor Avula, because of his participation in the mayoral forum for the arts and the things he said, that he’ll be a man of his word and follow up in supporting the larger arts community.

When deciding on a project, do you guys take ideas to your board at Collaborative Arts, or do they suggest stuff, or both?

Criqui: So, the board is like our oversight, we check with them about strategy. As executive director, I kind of make those day-to-day decisions. Part of the funding we have is earmarked for Reclaiming the Monuments, the larger project that Dustin and I have been doing since 2020. So we have input from our small board, which is just five of us, Dustin and I are on the board as well. It’s all local artists and activists. We’re really hoping to keep this an artist-driven nonprofit and put resources directly in the hands of artists, that’s our mission. This project in Blackwell this week is really about helping highlight the importance of public art, like Dustin said, all the ways it benefits our community. But also, hopefully it helps provide people with an accessible entryway into public art, because it can be difficult field to get into.

I’m sure it was a major validation to have The New York Times describe the reconfigured Lee statue, covered with protest graffiti and also featuring your projections, as the “most influential work of protest art since World War II.” Were you ever surprised by the widespread, international media coverage?

Criqui: Oh yeah, for sure, the whole thing was unexpected and took us by surprise. I mean, we got featured in El País, which is the biggest paper in Spain [or second in terms of circulation]. They came out to Richmond and we got interviewed for that. My little dog got to be in a Spanish newspaper, so that was cool …

We met with one of The New York Times’ art writers. That was a crazy moment of attention, and we were part of that moment of energy in our city, and energy nationally. I think we’re still reaping the goodwill from that, and so now we’re still trying to, as we did in 2022 and 2023, to take that energy and those opportunities and put them back into our city, and into other artists—and speak to the greater good via public art.

We’re hoping to build a new type of momentum that can not only fund public art but sustain itself and continue to help artists for years to come.

Flow will be held on Saturday, April 12 at 1621 Hull St. from 6 p.m. to 10 p.m. It’s free, of course, to attend. For more information, follow them on social at: 📷 @collaborativearts | @mendingwallsrva | @videometry

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.