When Lupe Fiasco first burst onto the scene in 2006, he seemed anointed for rap stardom. The then 24-year-old had caught the eye of Jay-Z, the reigning king of hip-hop, who saw a younger version of himself in the Chicago rapper. Hov helped Lupe get a record deal with Atlantic Records, and even sat in as a producer for his debut album Lupe Fiasco’s Food & Liquor, which earned widespread critical acclaim and three Grammy nods for its immersive, fantastical story-telling and deeply insightful meditations on Islamophobia, racism and American gun culture.

2007’s follow-up The Cool—a concept album a young boy raised by The Streets and The Game (both personified as characters in the narrative)—built on that success, debuting at #15 on the Billboard Top 200 chart, and at #1 on the rap chart. The album cemented his reputation as one of the most promising rappers in the game, offering a philosophical, even nerdy take on a genre that had come to be dominated by the hyper-violent machismo of gangsta rap.

But Lupe, it seemed, wasn’t built for the games that the music industry loves to play. The delay in releasing his third album, Lasers, apparently because Atlantic Records didn’t think it had enough commercial singles, kicked off a rift with his label that would derail his upward trajectory. When it finally came out in 2011, two-and-a-half-years late, Lasers debuted at #1 On the Billboard Top 200, a smashing commercial success. But his next two albums with Atlantic would face delays and conflicts of their own, leaving Lupe embittered with the mainstream music industry and its crass commodification of hip-hop culture.

Lupe’s anti-establishment politics, and his unwillingness to compromise on his ideals, also made him plenty of enemies. In a 2011 interview with CBS, he criticised the US government and Barack Obama’s foreign policy, calling Obama “the biggest terrorist.” Two years later, he marked Obama’s inauguration by performing a 30-minute version of a song with anti-Obama lyrics at a gig in Washington DC, eventually having to be herded off by security. His political views, as much as his fights with Atlantic, ensured that he became, as Lupe put it in a 2019 tweet, “the most blackballed rapper in the history of rap.”

So, even though Lupe remains a rap-nerd favourite for his masterful lyricism and incisive socio-political commentary, his music over the past decade has fallen off the charts. The heir apparent of the conscious rap crown is now a prince in exile—a lone man navigating the wilderness armed with only his words as weapons. It’s a role that Lupe seems to enjoy, making the most of his freedom as an independent artist to create records that are both whimsical and profound, such as 2018’s Drogas Wave (a concept album about escapees from a slave ship who become an underwater anti-slavery force) and 2022’s Drill Music In Zion (a critique of contemporary hip-hop and how the music industry commodifies real-world death and violence).

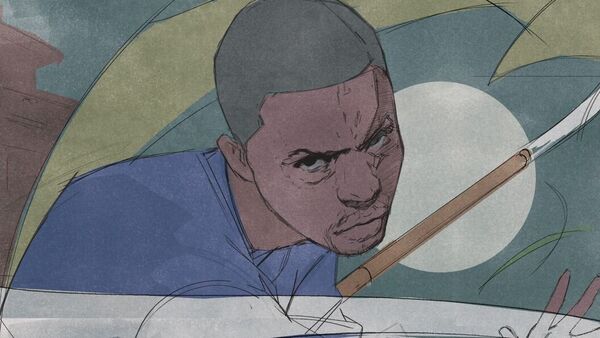

It’s a role that he fully buys into on his latest album, Samurai. The 30-minute eight-track record is ostensibly a concept album that reimagines late English singer Amy Winehouse as a battle rapper. Lupe was inspired by a segment in the 2015 documentary Amy, featuring a voicemail from the singer-songwriter to producer Salaam Remi where she says she’s been writing battle-rap rhymes and that she’s become a lyrical “Samurai.” From that one sentence, Lupe conjures up an epic narrative arc for Samurai Amy—her days as a struggling jazz singer in North London, the heady highs of post-battle victory laps and the dizzying lows of dealing with a hyper-exploitative music industry.

Lupe has never been one for unidimensional narrative though. He sees obvious parallels between his and Winehouse’s struggles with the music industry, and the verses on Samurai flit between Winehouse role-playing and autobiographical self-portrait, as he raps about the sheer thrill and joy of intricate (s)wordplay or the insecurities and doubts that accompany fame. Longtime collaborator Soundtrakk—the album’s sole producer—creates a smoky, hypnotic jazz-rap soundscape for Lupe’s tongue-twisting bars about gentrification and social media narcissism.

References to Kurt Vonnegut and the iconic Gagosian Art Gallery sit comfortably alongside anime shoutouts and Japanese karate shoutouts, as Lupe showcases the depth and breadth of his intellectual and cultural influences. Over Mumble Rap’s 90s jazz-inflected boom-bap beat, he sketches out a fever dream about being possessed by hip-hop and revelling in the power of rap music. The mournful minor keys on Palaces set the mood for the track’s ruminations on the darker side of fame, while BigFoot has Lupe rapping and singing about the trials and tribulations of an artist in a capitalist society over chopped up piano breaks.

Lupe has always been a cerebral rapper, wrapping academic debates and radical philosophy within his flights of whimsical fancy. But on Samurai, he finds the perfect balance between the intellectual and the personal, his lyricism honed even sharper by his years of practice in the relative isolation of the indie rap scene.

“I was Bill of Rights and Ted Talks meet the TARDIS before it all started,” he raps on elegiac closer Til Eternity. “But you can’t harvest before the hardship.” It’s hard to argue that Lupe hasn’t dealt with his share of hardships, documented on Samurai as well as previous records and interviews. But rather than break him, Lupe’s trials have only sharpened his socio-political critiques of American society and the culture industries. He’s emerged with hard-won insight into the human condition, and how it’s shaped by the world we live in. That insight makes Samurai an incredibly compelling portrait of the ethical artist, buffeted by the forces of capitalism and alienation, but kept afloat by his commitment to art and community.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.