Other old signs are clearly personal, handprints or names. Their significance is as a record of presence: ‘I was here,’ says the signer.

Why they were written is a different question to how they are read: the observer might see vandalism, identity-signalling, a form of art or some combination of all three. Anyone who thinks about this at all, probably, is reminded of dogs, and that’s not meant as a cheap joke: marking your territory is important to all kinds of animal, humans included.

The difference between traditional and modern forms is principally, it seems, a product of mass mobility. Anyone can write in a place where they just happen to be, particularly if they’ve got nothing better to do, and you’ll find a lot of names scratched into prison walls. But going to a place specifically in order to write your name there is a recent development.

Tagging as it’s now understood seems to have started on the US railways in the 1960s or thereabouts, and a lot of the terms you’ll read on Wikipedia are Americanisms, but other countries have their own words for styles or techniques: a dub is UK-English for silver writing outlined in black, and a strip is what you get when you spray solvent on a British train, to expose the metal. You can’t do it in other countries because the trains have different coating that turns messy if you try to strip it.

These are things I know from talking to 10Foot. I’ve still got a lot to learn, but he’s educated me to some extent. For a start, don’t call a graffer a ‘street artist’. I had thought there was a certain mutual respect between taggers and the designers of murals, but I was wrong: even a splendid political painting under the Westway flyover has been defaced, and the council-sponsored designs you see in trendy bits of London like Shoreditch are fair game for respraying. On the other hand, I can attest to a West Hampstead bridge decorated by schoolchildren which has stayed intact for over two decades.

There is art in a tag – design and technique, whether with a spray can or a marker, are as integral as the words – but the important thing is where it is. I WAS HERE means much more, if it’s a place that’s hard to access, whether because it’s physically dangerous or because it’s a long way off. Tox, a ‘king’ in the culture, went to the Arctic Circle, purely in order to tag there. His status is high even among rail workers, who write his tag up in their training sessions when the supervisors aren’t looking.

How people interact with environment is a long-standing interest of folklorists, but historically the focus has been on the rural and pre-industrial. Even today, there’s a tendency to classify as ‘folklore’ or ‘folklife’ only what appears in some way ‘traditional’, and to identify the ‘environment’ as the natural world. But a city landscape, self-evidently constructed, is still a habitat, and it’s the one most of us, these days, inhabit.

Studies of urban folklore have been made, but the starting point is often either on culture preserved by migration from the countryside or from other countries, or on the ‘problems’ of city life. To examine an inherently street-based culture, on its own terms and without value-judgement, means talking to both practitioners and observers. So far I’ve only done a little of that, and I hope to do more.

From the practitioner side, there’s a perception of themselves as adventurers. Like pirates, smugglers, or highwaymen, taggers need to be speedy, fit and deft, and travel is as integral to the new practice as it was to the older ones. Unlike piracy or highway robbery, though, there is no profit motive to tagging.

It is, you could say, the ultimate ‘outsider art’, in that the artists are to some extent social outsiders, certainly outside the established art world, and what they do is literally outside. People who complain that today’s youth spend too much time in their rooms on their screens should approve of it, but probably don’t.

Illegality is a key factor – but graffers don’t just run the risk of arrest. Writing on a bridge over a motorway, or on a track next to the tube lines, takes nerve and skill, and you can only learn on the job. Courting danger and breaking rules are now, as they’ve always been, ways of proving and defining yourself against a restrictive world.

What taggers do is assertive but not aggressive. Writing is by its nature less confrontational than speech, and even if what you’re writing is FUCK OFF, that’s not the same as saying it to someone’s face. Around where I live, it’s rare to read insult or obscenity. Sometimes you get politics or protest, and one Kilburn regular writes whole paragraphs: ‘I have a love for humanity but some humans leave me with only homicidal contempt’ is a comment I can endorse.

Recognising a tag, especially if I know whose it is, is like seeing someone I know in the street. On film, shots of graffiti are usually shorthand for ‘run-down decay’, but that’s not the way Kilburn feels, or anyway it’s not how I feel about Kilburn. To me, reading the walls has become a kind of conversation, a series of daily meetings, and I was grieved when one of my regular routes was cleaned. The temporary nature of words is inevitable, but this is a particularly ephemeral form.

I’m not the only person with emotional attachment to graffiti. Sadly vanished examples include GIVE PEAS A CHANCE over the M25. When another graffer wrote over the top of it, a petition to Network

Rail to reinstate PEAS was signed by over 2,000 people (without result, like so many petitions).

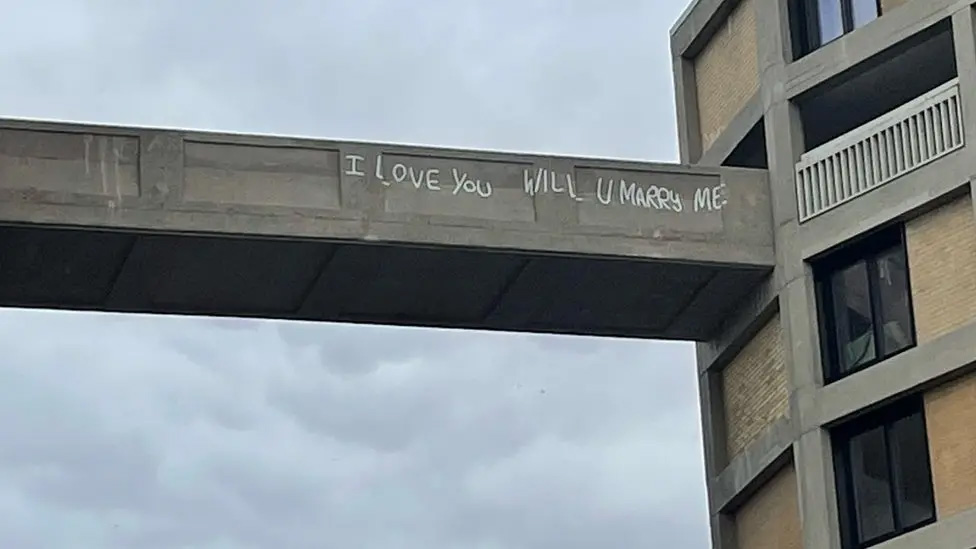

There was a longer story in The Guardian a few years ago, about a marriage proposal written 13 floors up on a brutalist block, which looked ‘like love yelling at the top of its voice in an estate thought to be desolate’. Five years later, I LOVE YOU WILL U MARRY ME had become a slogan used by developers in an ‘urban regeneration’ scheme, printed on t-shirts and cushions and referenced at the 2006 Venice Biennale of Architecture.

By 2010, stories were in circulation that the writer had ended their life by jumping off the block (not true). In 2011, 10 years after the words were written, they were replaced by the developers with a new version in neon, and used by a brewery to promote their beer. The graffiti, said film-maker Penny Woolcock, had been “drained of meaning, transformed into a hipster brand advertising gentrification”.

Like any art, graffiti is vulnerable to exploitation, and to some extent it’s been mainstreamed. For a while it had a bestselling magazine, Graphotism. It has Banksy, nuff said. But at street level (or however many floors up) tagging is a real live practice among real live people who do it because it’s what they do.

We are all the folk, and the lore we share is whatever attaches us to a network: kinship, place, or work, or in this case a tribal occupation or preoccupation.

Folklore is, to quote a 20th-century academic, “expressive, stylised communication performed within and for” a group with common experience, to create “a feeling of egalitarian community against the structured world”. It defines identity, a sense of belonging to one set of people, as against those who do not take part in or understand the lore. Tagging is folk practice. But it’s not likely to make it onto the Intangible Cultural Heritage list any time soon.

Do you have a story to tell or opinions to share about this? Get in touch and tell us more. Big Issue exists to give homeless and marginalised people the opportunity to earn an income. To support our work buy a copy of the magazine or get the app from the App Store or Google Play.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.