For centuries, a rectangular room at the summit of Mount Sion was a stirring motivation for Christian crusaders. Located on the upper floor of a building just outside of Jerusalem’s city walls, the Cenacle was identified as the site of the final meal that Jesus shared with the 12 apostles before his arrest and crucifixion.

The Cenacle is thought to stand on the site of King David’s tomb and remains a place of pilgrimage. Today, tourists can look in on a room of stone and marble with Gothic rib vaulting that was likely built in the late 12th century. One element that was long invisible to visitors are the numerous graffiti that were left by Christians who made the pilgrimage between the late 14th century and early 16th century when the Cenacle was part of the Franciscan Monastery of Mount Sion.

Carved coat of arms with the inscription “Altbach.” Photo: Shai Halevi / © Israel Antiquities Authority.

After the Franciscans were kicked out of Jerusalem following the Ottoman capture of the city in 1517, a thick coating of white plaster was layered over the walls, layers that remained until the room was restored in the mid-1990s. Now, in the first part of a comprehensive study, researchers from the Israeli Antiquities Authority and the Austrian Academy of Sciences have documented and analyzed 30 inscriptions and nine images marked onto the walls of the Cenacle. The findings have been published in Liber Annuus, a journal focused on theology and Biblical archaeology.

Collectively, the markings offer a vivid depiction of the range of Christians who passed through the Cenacle. We meet Johannes Poloner, a German pilgrim whose account of visiting the Holy Land in the early 1420s survives; Adrian I von Bubenberg, a Swiss knight famed for his defense of Bern in 1476 (20 years later, Adrian’s son also left his mark); Jacomo Querini, who belonged to one of Venice’s patrician family; and Lamprecht von Seckendorff, a Franconian count.

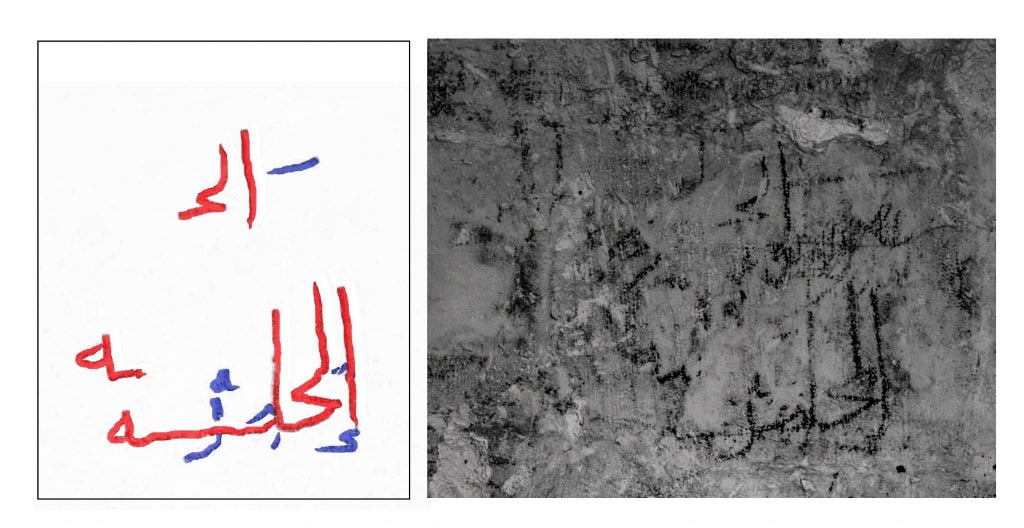

The graffiti of a pilgrim from Aleppo. Her inscription [red] crosses another Arabic graffiti [blue] that has not yet been deciphered. Photo: Shai Halevi / © Israel Antiquities Authority.

These are only a handful of visitors who made themselves identifiable by word or drawn family crest. Inscriptions in Latin, Armenian, Cyrillic, and Arabic point to the broad range of Christians that visited.

“When put together, the inscriptions provide a unique insight into the geographical origins of the pilgrims,” said Ilya Berkovich, one of the paper’s authors. “This was far more diverse than current Western-dominated research perspective led us to believe.” This group spanned Armenians, Czechs, Serbians, and Arabic-speaking Christians who lived in the East.

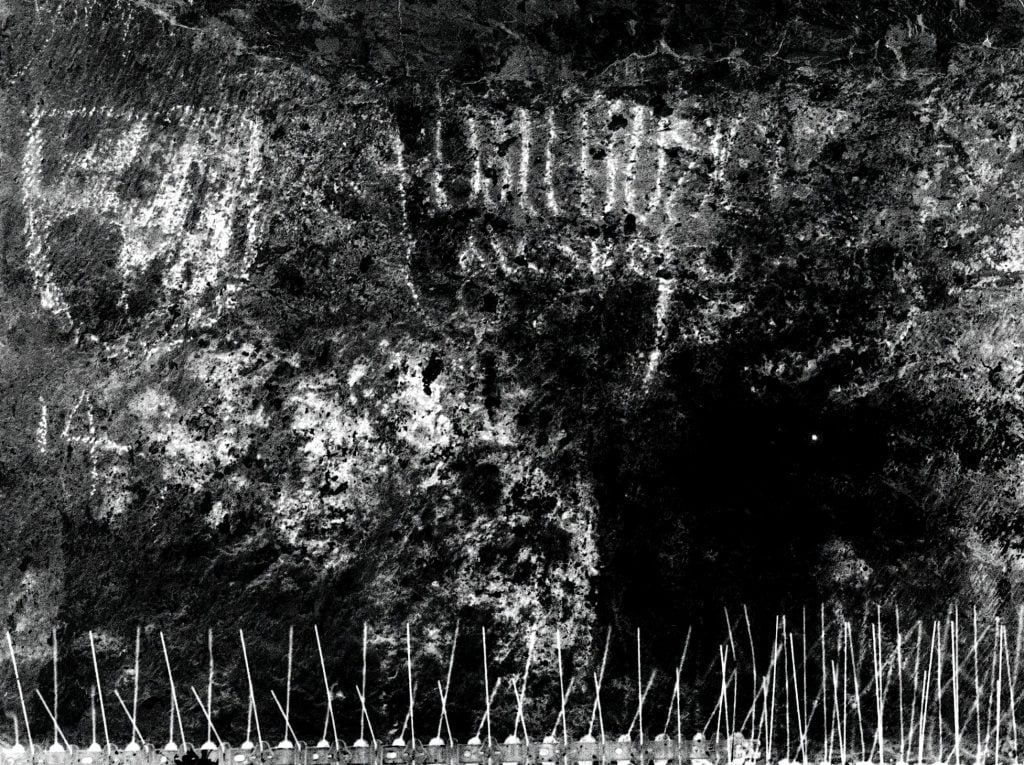

Digitally enhanced black and white multispectral image of the “Teuffenbach” coat of arms from Styria. Photo: Shai Halevi / © Israel Antiquities Authority.

After conducting a thorough visual survey of the room with ultraviolet and infrared filters, researchers predominately relied on two photographic techniques. First, Reflectance Transformation Imaging, which highlighted the physical surface of the walls and helped identify worn out markings. Second, multispectral photography that made it possible to identify specific chemicals used in ink, coal, and paint. These were then digitally processed and analyzed by linguistic experts.

While researchers were excited by the wealth of information they were able to suck out of the walls, a puzzling question remained: why were pilgrims allowed to tarnish a site that was supposedly one of Jerusalem’s most important shrines? In fact, given some of the more elaborate markings would have taken many hours of work, it seems possible that the Franciscans condoned the graffiti.

Inscription and scorpion drawing in honor of the Sufi Sheikh Ahmad al-ʿAjmī. Photo: Shai Halevi / © Israel Antiquities Authority.

“The attitude of the Franciscans to that subject was ambivalent,” the authors wrote. “The situation in the Cenacle is consistent with what is known about the phenomena of church graffiti in Western Europe.”

One individual who was the opposite of ambivalent towards the pilgrims and their place in the Cenacle was Sheikh Aḥmad al-ʿAǧamī. It was at his insistence that sultan Suleiman the Magnificent expelled the Franciscans and something like a retort is scoured onto the walls. First a monumental Ottoman dedication that mentions him and second a scorpion that references him by way of a Sufi symbol. Made indelible with hammer and chisel it continued room’s tradition of the wearing history on its walls.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.