Rapper BossMan Dlow hit the stage at Detroit’s Aretha Franklin Amphitheatre last month as one of the hottest emcees of the summer, fresh off the cover of XXL’s “Freshman Class” 2024. However, the Florida native only performed his hit “Get In With Me” and a couple of other crowd favorites before his performance, part of a concert dubbed “We Up Now,” ended.

“He did three songs and everything stopped,” says an attendee, who prefers to remain anonymous. “They stopped the show.”

In a statement, Keith Jackson, owner of UEG Promotions, one of the show’s promoters, downplayed the incident. “The We Up Now show that took place on Saturday, July 6, at the Aretha Franklin Amphitheatre was neither halted nor stalled,” the statement read. “BossMan Dlow performed, and the show proceeded as planned.”

However, the next morning, local hip-hop phenom Skilla Baby took to Instagram to voice his frustrations about his set at that same show being cut short. And it wasn’t the first time.

“Every time I perform at home, fire marshals or Detroit police always come shut me down,” the rapper says in the clip, shared with his 1.3 million followers. “I don’t know what I be doing, but they always come shut me down.” Skilla even claimed he has been targeted by one particular DPD officer and threatened to sue the city over it.

In several videos posted to social media sites from the July concert, a shirtless Skilla Baby can be seen on stage angrily yelling at police and fire authorities, “Y’all can’t bully me no more!” A police officer can also be seen talking to Skilla’s manager East Side Juan making a “cut it” hand gesture (implying to cut Skilla’s set). Skilla is then restrained by concert security while trying to interact with fans in the first two rows at the Aretha before he eventually exits the stage.

Speaking on behalf of the show’s promoter UEG Promotions, in a follow-up phone interview Erica Banks of Bankable Marketing Strategies says that Skilla was not technically scheduled to perform that evening and his appearance was more of a surprise treat for the fans. In hip-hop, it’s common for national touring acts to bring local artists onstage for a few songs, like Detroit faves Peezy, Icewear Vezzo, and 42 Dugg recently giving surprise performances at the August 4 stop of Future and Metro Boomin’s “We Don’t Trust You Tour” at Little Caesars Arena.

Nonetheless, even though Skilla was not on the show’s official roster, he was still stopped from performing the entirety of what he had planned — which is what he was venting about. “They kept cutting his mic while he was on stage trying to bring out [fellow Detroit rappers] Sada Baby and Tee Grizzley,” the anonymous source says.

The onstage drama was a bitter end to what had otherwise been a festive day for the 25-year-old Detroit native. Earlier, CBS News filmed and profiled the rapper on Detroit’s west side, which was followed by an interview on one of hip-hop’s top podcasts, Million Dollaz Worth of Game.

In his Instagram video, Skilla Baby accused DPD Lieutenant Lacell Rue of being the reason there were so many hiccups planning his birthday bash concert that was originally scheduled to be held at Masonic Temple on September 30, 2023.

“He shut me down, made me get a venue last-minute,” Skilla said in the video. “The week of [the show he] made me get a different venue. I had already paid a certain amount of money, I had to pay 80 more thousand to get another venue, 50 more thousand for production, and a couple more thousand for 100 security guards. He made me change my stuff the day of, he went to Masonic Temple and told them people I’m a gangbanger, I shoot people, I kill people, and I’ve never even been arrested in Detroit.”

Last year, DPD responded to Metro Times’s inquiry about the canceled Masonic Temple show, saying, “The decision to cancel Skilla Baby’s concert was the venue’s own decision.” The show was then moved to Detroit’s Riverside Marina, which was also shut down only a few songs into Skilla Baby’s set due to organizers not having “proper use permit, security, or emergency medical staff onsite,” according to Detroit Fire Department chief James Harris.

In his Instagram video, Skilla Baby went on to highlight his philanthropic endeavors in Detroit and his positive relationship with DPD, but he also claimed Lt. Rue tried to use his influence to deny him entry into a high school football game at Ford Field last year.

“The next thing I’m going to do is sue the city,” Skilla added. “I’m going to sue the DPD for [putting] him at my events.”

In a statement, DPD denied Skilla’s claims.

“The Department has reviewed the allegations contained in the video created by the rapper commonly referred to as Skilla Baby,” the statement reads. “We deny any suggestion of wrongdoing toward the performer or his events. While several of Skilla Baby’s concerts have been canceled, this has been due to the performer failing to follow city protocols and for failing to obtain venues with the appropriate capacity. Questions regarding specific violations should be forwarded to the [fire marshal].”

The Detroit fire marshal did not respond to a request for comment, nor did Skilla Baby’s camp.

The We Up Now Show was one of several local hip-hop concerts to be interfered with by police in recent years. On August 11, 2023, entertainment company 313 Presents canceled a show by the New York-based hip-hop group Beast Coast after local police departments received separate phone calls about the possibility of a mass shooting occurring at Michigan Lottery Amphitheatre. Less than two weeks later, on August 20, a Moneybagg Yo show at the Aretha Franklin Amphitheatre was shut down due to capacity and crowd control issues.

Courtesy photo” class=”uk-display-block uk-position-relative uk-visible-toggle”>

Courtesy photo

Anthony Thompson II is an operations manager for Live Nation and CEO and founder of ATNetwork Production Studio.

“The police here in Detroit get intel, it might be street stuff going on you don’t know about,” says Anthony Thompson II, an operations manager for Live Nation and CEO and founder of ATNetwork Production Studio. “Because we find that out too, they give us heads up on certain things.”

Mark Hicks, one-time manager of Detroit hip-hop collective D12, says there has been police involvement in the hip-hop scene for over two decades at the hands of DPD’s “Gang Squad,” a special paramilitary unit of the department known for being more heavy-handed and street-savvy than your average police officers.

“They kept a real beat on the rap game here,” Hicks says. “They followed the hip-hop culture like we did. When they would hear rumors about different things they would follow up and tell their police chief.”

The Gang Squad unit was broken up and reorganized in 2013, and although police have historically had an adversarial relationship with Black people, Thompson says it’s important for the general manager of a concert venue to have open lines of communication with the police and fire marshal. He says it’s common for either to walk around inside of the venue and observe what’s going on during a show.

“[All] these folks, EMS, and police, fire departments are all connected,” he says. “I just feel like Black artists and Black people all over are overpoliced, and they don’t do that with white artists, they don’t do it at that level.”

A music industry professional who goes by Six Two, who previously worked as a junior talent buyer for Live Nation at Saint Andrew’s Hall and the Shelter and also promoted her own events, says in 2015 she rented out a venue outside metro Detroit for a Beanie Sigel and Freeway concert that garnered police attention.

“The police brought me Beanie Sigel’s record, his public arrest record, and mentioned to me that if I was going to go through with this show, the kind people that would be attending this show would be in line with the rap sheet I was being shown of the artist,” she says.

Drug use, arguments, and fights happen at many concerts, festivals, and sporting events. When Thompson says, “they don’t do that with white artists,” he’s not stating that police don’t make their presence known at non-Black events. But there can be an extra aggressiveness shown toward Black crowds and Black artists, he says.

“So it happens, but it’s viewed differently,” Thompson says. “It’s looked at as less threatening to even police and security. They feel more comfortable breaking up a white boy fight and letting them walk away like, ‘Alright guys, it’s over.’ Some Black guys get into a fight and everybody is nervous.”

Courtesy photo” class=”uk-display-block uk-position-relative uk-visible-toggle”>

Courtesy photo

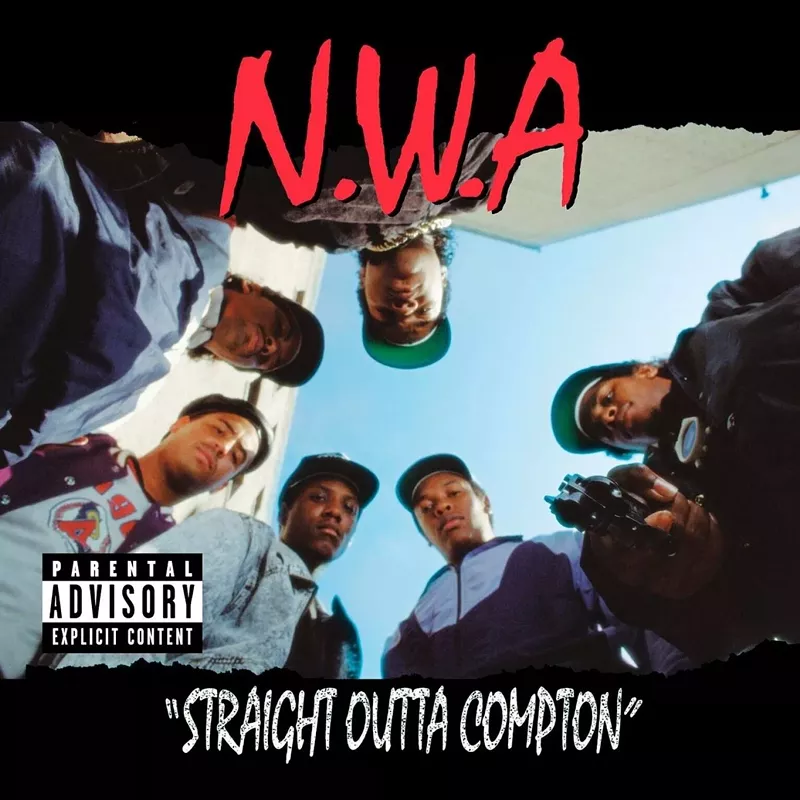

DPD infamously warned hip-hop group N.W.A not to play “Fuck tha Police” at a Motor City concert.

A complicated history

Shows being canceled, postponed, or shut down is just as much a part of hip-hop culture as the emcee and the DJ. As the energy of hip-hop matriculated from the Big Apple to the Big Axel in the late ’70s, Detroit’s talented hip-hop artists struggled to consistently book large venues to entertain their blossoming fanbases.

Kalimah Johnson, who performed under the monikers “Nikki D” and “Eboni and Her Business,” was a part of Detroit’s first wave of ’80s hip-hop artists and recalls multiple issues. “Venues would back out of shows for lack of planning, low presale of tickets, fear of violence, or straight scamming because some venues would charge us to perform,” she says.

“History is the best teacher,” adds Lamonte Hayes, a music industry veteran and founder of BWP Marketing. “If you understand the history of hip-hop, it’s always been a genre of music where venues have always been afraid. If you remember back in the ’70s and ’80s they didn’t allow rap concerts at all.”

The issues weren’t always confined to local talent, and some of hip-hop’s biggest stars faced debacles on their Detroit tour stops. At an August 6, 1989 show at Joe Louis Arena, Detroit police infamously warned hip-hop group N.W.A not to play “Fuck tha Police.” The group performed the controversial track anyway, darted off the stage before finishing, and were greeted by Detroit police officers back at their hotel rooms. (A much more dramatic version of this was shown in the 2015 biopic Straight Outta Compton.)

On July 14, 1995, a concert at the Aretha (then known as Chene Park) featuring Notorious B.I.G. was threatened to be canceled by DPD, who claimed the Brooklyn native had received death threats prior to the show. And a December 4, 1998 concert featuring mega groups Outkast and Black Eyed Peas had to be moved to Harpos after the previous venue backed out the deal.

“Back then if the Fox was tripping, Joe Louis was tripping, you could take the concert to Harpos or Eastown Theater,” Hicks says.

On July 6, 2000 Dr. Dre’s “Up in Smoke Tour” featuring Snoop Dogg, Ice Cube, and hometown hero Eminem was delayed over an hour because DPD didn’t want to allow a sexually explicit video to be shown. “It was very close to being shut down,” says Hicks, who was there at the time. “It was at high-end levels at that time. [Police] were all backstage and literally holding up shit.”

“You can call it ‘Black,’ ‘urban,’ whatever you want to call it, but it’s always been treated differently than other forms of music,” adds Hayes.

Much like the N.W.A concert more than a decade earlier, the incident has been viewed as a case of police flexing their muscle and getting high off their own egos. Ultimately, the video wasn’t shown and the concert went on. The debacle was filmed and added to the Up in Smoke DVD released in December of 2000.

Kahn Santori Davison” class=”uk-display-block uk-position-relative uk-visible-toggle”>

Kahn Santori Davison

Skilla Baby performing at the Fillmore.

Budgets, ticket sales, and marketing

Over the last six years the fever of Detroit’s hip-hop community has reached an all-time high. Artists have been enjoying features with national hip-hop acts and several top 10 charting debuts. There’s nearly three dozen Detroit hip-hop artists signed to major record labels or having inked major distribution deals.

But popularity and millions of streams don’t always equate into concert ticket sales. In recent years, many of Detroit’s favorite emcees have quietly canceled concerts with no explanations. One second the event is listed on Ticketmaster, and the next minute you’re getting a “link not found” message on your phone when you go to buy tickets.

It’s much the same with national touring artists as well. Veteran New York emcee Busta Rhymes quietly canceled his tour that had a planned April 11 stop in Detroit, while Georgia emcee Playboi Carti scrapped his highly anticipated tour with an October 4 stop.

When no explanation is given, the assumption from fans is that “ticket sales” were the reason, but it’s more intricate than that. Despite hip-hop’s commercial dominance, its concert and touring budgets aren’t as big as other musical genres and aren’t privy to the same kind of promotional dollars spent.

Courtesy photo” class=”uk-display-block uk-position-relative uk-visible-toggle”>

Courtesy photo

Lamonte Hayes is a music industry veteran and founder of BWP Marketing.

“You don’t need a band, just a DJ,” Hayes says. “The allure with hip-hop with major companies was that it was always cheap to make. They would make a lot of money and take the resources from that cheap labor and you put it over there to the crossover top 40 side.”

“It’s not fair — marketing dollars, it’s not on the same level,” Thompson adds. “Look at the numbers. Look at the billboards. Look at the ads purchased. It’s not the same playing field, but I don’t think it will ever be.”

From the outside looking in, hip-hop is still a great place. Statista published a report earlier this year showing 54% percent of music fans between 20-24 named hip-hop their favorite music genre. The concert industry also appears healthy as Live Nation, the world’s largest live entertainment company, reported operating income of almost $46.8 million, which was up 21% for the second quarter of 2023.

However, Civic Science reported that 36% of consumers say they will spend less on concerts and live performances this summer. A Yahoo! Finance poll showed that 54% of people aren’t going to spend more than $50 concert tickets, and 35.2% aren’t going to spend more than $150. None of that is good news for a genre that depends on a fanbase with a limited disposable income who are getting bombarded with more concerts than they have time to attend. Per SeatGeek, the average price of a hip-hop concert is $134.

“I think the artists and the industry are stressing the consumer financially,” Hayes says. “I think we got too many shows in the marketplace […] Hip-hop is also a last-minute market. That’s a known fact, but you also have to understand why — because you still have DTE, you still have to put gas in your car, might have child support, you might need some stuff from Costco. People have real-life expenses.”

“There’s that habitual cycle where fans wait to buy tickets because they’re afraid it’s going to get canceled, and it gets canceled because they waited too long to buy tickets,” adds Six Two.

“One thing I know from working in the touring industry, we talk a good game as our people but we don’t show up like that,” Thompson adds. “It be mostly white folks at these hip-hop shows.”

In order to maximize a tour’s earnings potential, promoters will oversell tickets at general seating venues knowing that a percentage of patrons won’t show. This is one of the reasons hip-hop concerts encounter capacity issues frequently. They might also book an arena tour for an artist that doesn’t have the streams or analytics to back it up with hopes the artist will pick up momentum. When that doesn’t happen, they’ll seek to kick down the show to a smaller venue (like a club or theater) or even skip several markets altogether, as Atlanta rapper Lil Baby did when he canceled seven dates on his “Only Us Tour” last year.

“The majority of acts on the road should only be doing theaters, 3,000- to 6,000-seat venues, and selling them out,” says Hayes. “Even if you do two or three nights of those, that’s much better than trying to go for a big arena. And to be honest, you’re going to give a better show in a theater than in an arena. Everybody isn’t built for arenas. It’s a money grab.”

When ticket sales look bleak for a local one-off show, venue general managers and promoters can be eager to cancel a show altogether as there won’t be any way to make a profit. “If you’re not selling tickets and you’re not going to have anybody in that room, then how are we going to know how to staff our space?” asks Lauren “Lo” McGrier, who’s managed Southwest Detroit’s El Club since 2021. “If I’m going to have all these security guards, and all these bartenders, and my insurance for the day, and I’m not making no bar, then what am I opening for?”

McGrier and Hayes both believe this is the reason you see more Detroit hip-hop artists coming together to do concerts. The results of combining multiple fanbases and giving patrons the chance to see several of their favorite acts on the same stage stand the best chance of delivering a sell-out show. Earlier this year, Detroit hip-hop groups Team Eastside and Doughboyz Cashout caused buzz when it was announced they would reunite onstage at the January 19 show headlined by 42 Dugg at Little Caesars Arena.

“In my opinion, outside of Team Eastside and Doughboyz Cashout, I don’t think I’ve ever seen a local act that had that many people truly excited about going to an arena,” says Hayes. “And yes, there were other people that were on it, but if you go back and look at the sales history of the data, the majority of the ticket sales were sold when it was announced that those guys were going to be on the show.”

Kahn Santori Davison” class=”uk-display-block uk-position-relative uk-visible-toggle”>

Kahn Santori Davison

Lauren “Lo” McGrier has managed Southwest Detroit’s El Club since 2021.

The need for more Black-owned venues

By nature, hip-hop is communal. It has always needed an alignment and synergy between the artists, supporters, and venue managers, and some of Detroit’s most memorable moments were enabled by venue owners and managers that understood the needs of its participants. The Hip Hop Shop is legendary because owner Maurice Malone made it accessible to everyone. When Big Proof died on April 11, 2006, Mike D who, who managed Saint Andrew’s Hall at that time, opened it at 10 a.m. so Proof’s peers and fans could congregate, pray, and mourn. (And this was after Saint Andrew’s had been sold to Clear Channel.)

“It was very much a community feel,” Six Two says.

Some of that same communal energy is at El Club. The small venue has become a fixture in southwest Detroit and a place where artists and promoters can throw shows without dealing with the obstacles and reservations of bigger corporate-owned venues in the city. “We know the culture, so it doesn’t intimidate us like it does other venues,” McGrier says.

McGrier states it cost at least $2,000 for her to open her doors, and El Club has been known to negotiate deals that bigger venues won’t. “We can reach a happy medium,” she adds.

BJ Pearson has also been an administrative mainstay of Detroit’s entertainment scene. He managed event operations at the Detroit Symphony Orchestra Hall for 11 years before becoming vice president of the Garden Theater in 2014.

“I’ve worked on both spectrums. I’ve seen both sides. Managing an independent venue, there are less hoops you have to go through. When you’re dealing with a corporate-structured venue you have to deal with union labor, you have to go through the board, and a whole panel of what kind of events you’re bringing,” he says.

However, being a “hip-hop friendly” venue doesn’t come without its hiccups. McGrier cites challenges like dipping bar sales because patrons are smoking marijuana more and drinking less, and the sense of entitlement that can be shown by large entourages of hip-hop artists.

“They have these long guest lists and those are the people who don’t want to stand in line, they give you a hassle at the door, and just the energy, it’s hard to deal with sometimes,” she says.

Her concerns aren’t new. Anyone who’s been to a hip-hop show in any era will notice the amount of non-performers who tend to be on the stage with the main act. Many times performances will be temporarily paused while the stage is cleared, because it seems that every hip-hop artist has a crew of close friends and family that they want to share the moment with. The solidarity is commendable, but problematic at times. (At the 42 Dugg show in January, the performance was paused, with a voice announcing, “If you ain’t a rapper, get off the stage!”)

“They want to showcase their family and friends. It’s a challenge, it’s a challenge to get them on stage and off stage. We as a venue have restrictions on how we can make it better,” says Pearson.

Six Two feels getting a list via a show rider of how many people an artist is going to bring in the venue and on stage (as touring acts do) would help mitigate any logistical snafus. “It’s never communicated that a large entourage is coming,” she says, adding, “The number of people allowed in the venue includes entourage, staff, artists, fans, everybody — and so when you’re bringing that many people in the back door you’re really creating a risk in terms of being over capacity.”

Courtesy photo” class=”uk-display-block uk-position-relative uk-visible-toggle”>

Courtesy photo

Mark Hicks once managed the Detroit hip-hop collective D12.

“Detroit is a very combative city sometimes, so I get why there are red flags, but 90% of the time it’s all good,” adds Hicks.

The Aretha Franklin Amphitheatre has been praised for how they work with the hip-hop community. The Right Productions, ran by Shahida Mausi and her four sons — Sulaiman, Malik, Rashid, and Dorian — have handled all aspects of programming and marketing for the venue since 2004. A quick click through the venue’s website and you’ll see concerts by jazz artists and legacy R&B acts alongside ’90s hip-hop emcees like Trick Daddy and local favs like Babyface Ray.

“That family is doing an amazing job,” says Thompson. “Respecting the venue, and selling out all the shows. They’re a Black family that runs it. They sell season tickets — how many Black folks got season tickets? Y’all want to see it get better, up the sales.”

Thompson believes more efforts should be made for more Black-owned venues in the region. The thinking is that if there were Black entrepreneurs from Detroit’s hip-hop community willing to acquire or open concert venues, then that would grow Detroit hip-hop’s independent culture and lessen the dependency on corporate venues or those with non-Black owners who don’t understand the culture and don’t want to.

The Garden Theater is the only Black-owned venue in the city with 1,000-patron capacity. It has hosted events like “Trap Karaoke” in 2019, premiered Al Nuke’s Detroit Dreams film, and held the first “313 Day” hip-hop concert in 2022.

“We want to make sure our venue is a staple to our community,” Pearson says. “To me it’s important that we keep hip-hop and R&B in our community. It’s a major thing in our community, to bring it to a nicer venue in Midtown, downtown Detroit, to a Black-owned establishment is a honor of our company.”

Both Thompson and Hayes hope that more Black general managers and owners would establish a stronger communal approach and working relationships that Detroit hip-hop has always needed.

“You would have people who really know who an artist like Skilla Baby is,” says Hayes. “A lot of these owners, they don’t know who they are, they don’t know their story.”

“I want to see more Black venue owners,” Thompson says. “I want to see more Black executives. I think that will help put things on more of an even playing field. I kind of fault us as a people at times too because when are we going to come together and do some things to make it happen?”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.