2023 marked the 50th anniversary of hip-hop, the music and social movement born in The Bronx district of New York and comprising the ‘Four Pillars’ of DJing (or turntabling), rapping (MCing), graffiti (writing) and breakdancing (B-boying). From its early days, hip-hop became a social movement for disaffected urban youth across the USA, before hitting the UK and Europe in the mid-1980s.

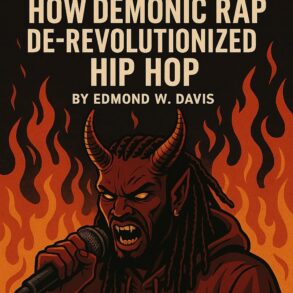

Man with the golden shutter

Normski’s Man With The Golden Shutter features 139 B&W and over 100 colour images, providing exclusive insight into the hip-hop movement in the 80s and 90s. Published by ACC Art Books, priced £45/$60.

Norman Anderson, aka Normski, was one of the pioneers of the UK hip-hop scene. As a youngster growing up in a Jamaican family in north-west London, he was fascinated by hip-hop. After trying breakdancing, he spent his time documenting the movement with a Kodak 126 Instamatic camera his mother had bought to cheer him up when he was ill.

From traveling around the US and the UK taking pictures of a genre on the brink of world domination, Normski then presented BBC ‘youth TV’ shows Dance Energy and Def2, and turned his hand to DJing, but it is his talent for interacting with people, his eye for detail and empathetic approach that make Normski’s photographs a unique record of the hip-hop genre. Now he has compiled a book, showcasing over 200 images from the scene, with artists such as Run DMC, Public Enemy, NWA and others.

Interview

Norman Anderson, otherwise known as Normski, is a British photographer, DJ and TV presenter. Growing up in London, he began documenting the early days of hip-hop culture in the UK and USA. His work has been exhibited in Tate Britain and is part of the permanent collections at the Victoria & Albert Museum and the Smithsonian National Museum of African-American History and Culture.

You have captured some of the most famous hip-hop artists with your lens. How did you first get into this genre?

Around the late 1970s, there was this new thing called hip-hop, a thing for young people that ultimately came from America to Britain. There were other movements, of course, but the hip-hop movement had all the cool clothes and the music was a combination of everything you thought you knew, but it was presented differently. So you stopped playing your parent’s records and you were able to get your own. Suddenly it wasn’t a record anymore, it was an object that was representative of our generation. That’s

when hip-hop caught me.

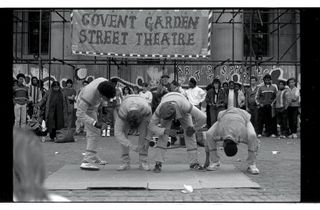

There was this mythical place called Covent Garden, where all the breakdancers were and lots of kids of all colors and cultures – you didn’t see that often at the time. For me, being a young black guy from London, I felt comfortable. I quickly realised that if I wanted to be part of the scene, I needed to do something to support it.

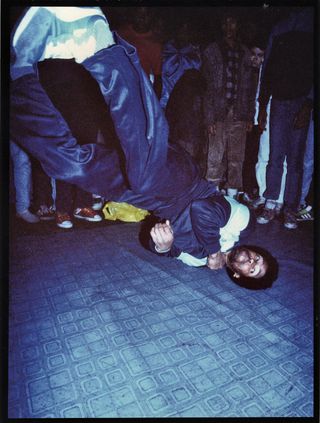

“Covent Garden in London was a mythical place for me, with so many breakdancers and kids of all colors and cultures” (Image credit: Normski)

So that was about the same time as your photographic journey started?

Yes, in a way. Even before that, I used a basic camera to take pictures at gigs. I realised that having a camera gave me a unique perspective, almost like a passport to be with real photographers – I found that very exciting. I was becoming a photographer by learning from watching all these pros. But I was never really comfortable with that kind of fighting to get good shots at a gig. I kind of got bullied out of it – you didn’t have lots of black photographers in the 80s. I had good shots and created a portfolio, so in the late 1980s, I got my first job at a magazine and focused on portraits instead of live shots. I always enjoyed taking portraits and, with this, I became a part of the hip-hop crew for a night.

What would you say has changed for black photographers starting out now, compared with your day?

Probably two percent of all photographers in those days were black, so not very much. But there were some photographers of African and Caribbean heritage who paved the way. These people had already established as black photographers doing work to represent the black community. That was fortunate for me. I got a lot of support and I was comfortable because I saw guys that looked like they could have been my big brother or uncle. Something happened. Nowadays, a lot of young black people are leaders in a range of creative fields.

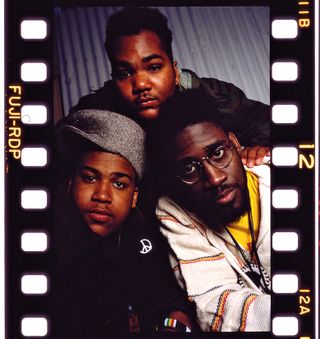

“Here’s De La Soul in one of those five-minute sessions, outside Brixton Academy in London in 1989” (Image credit: Normski)

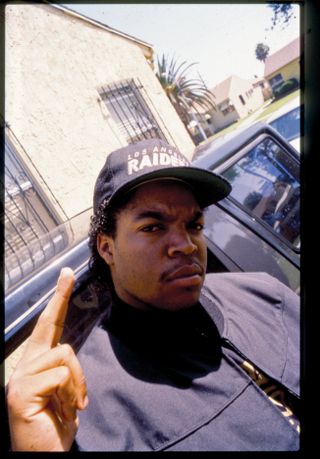

A contact strip of Ice Cube, taken outside his mother’s home in LA after he left N.W.A (Image credit: Normski)

In those past 40 years, photography has changed significantly. What are your thoughts on this technical revolution and do you still work with analogue?

Back in the 1980s, photography wasn’t something that was encouraged in a state school or normal comprehensive school. If you were going to a private school and your family had money, then you probably could have immediately gone into the arts.

In the beginning, I was never able to afford to go out and get films processed. I never had a dad’s camera to borrow. So, I went out and did some odd jobs to try and get a bit of extra money. Now, you can do photos a lot quicker with a lot less. You can buy a good camera for not much money, shoot non-stop for free, use a laptop instead of a darkroom and send pictures all over the world. Back in those days, you had to buy a camera, you had to buy film, and you had to ‘become’ a photographer. Now, you can even use your smartphone and act like a photographer…

DJ and music producer ‘Goldie’ said the difference between your photographs of him and anyone else’s was that it captures his soul… how did you gain this skill?

I take that as a really beautiful compliment but I’ve never thought of it as a skill. It’s quite rewarding because he works and has worked with the best. I’d think that is because, at that moment of photographing, I’m all in with the person, kind of on a soul level. I’m not just there to photograph because a magazine told me to. I don’t treat them like they’re big superstars. I am like a friend and I think that that might be the thing.

Some photographers are quite rough and direct people to create powerful images. I’m not good at being hard on people. If someone doesn’t seem comfortable, I want to know why. I often ask them ‘What would you like to do? Should we go outside? Where’s your favorite place to hang out?’. Then they’re leading the session and I can capture much more as they are offering much more about themselves.

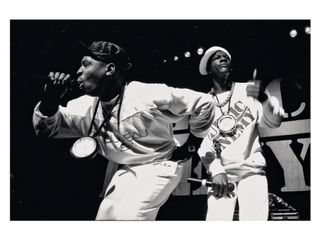

Hip-hop legends Public Enemy playing at the Hammersmith Odeon in London as part of the 1987 Def Jam tour (Image credit: Normski)

This anti-apartheid event at Camden Town Hall in 1986 brought Normski back to his north-west London roots (Image credit: Normski)

What do you do if you can’t leave the building or are restricted in time?

That’s a big thing and that’s what I hate about press photography. Often the manager says something like, ‘You can’t go outside, we’re in a hotel, five floors up. You only have 20 minutes to photograph because we have another photographer lined up…’

That was the case when I was photographing Salt-N-Pepa. Instead of staying in the same room where every press photographer captured them, I wanted to do something different. I asked if I could take a photo of them doing their makeup in the mirror, as they just started getting ready. So, I squeezed into this tiny bathroom with the three rappers and to get the right angle to capture their reflection in the mirror, I had to squeeze right in a corner. It was kind of funny to get this shot and we had a great time. I took them out of being big superstars, I go and meet the people and that makes a big difference.

Born in the mid-70s, breakdancing is an expressive art form that is tied to the rhythms of rap music (Image credit: Normski)

So in situations like that, would you say ‘less is more’ when it comes to camera equipment?

When I arrived for this shoot, another photographer just left with a big bag, lighting stands and more equipment. The press manager was asking me where all my stuff was, but I only had an Olympus 35mm, a couple of lenses and a flash. I never worked with a lot of equipment. There were times when I saw photographers with two camera bodies… two! I had my camera and lens, two or three films, that was it. And that’s enough, as long as you know how to deal with it.

And also the fewer people on set, the better. I don’t like having too many people behind or around me because then everyone tries to direct and half the people in front of the camera are looking at them instead of me. It’s essential to connect with the subject’s eyes and have their full attention.

The British rapper from the East End of London exudes a powerful energy as he interacts with Normski’s lens (Image credit: Normski)

You said you take them out of being superstars and that comes across when flipping through your new book, especially those images of sleeping rap stars. Can you tell us the story behind those frames?

It all started when I was noticed by a manager at one of their gigs. He was like, ‘What are you doing? Are you taking photographs?’. They came from America and didn’t have a photographer, so he asked if I would like to do that. I said ‘yes’ straight away. I ended up with a tour jacket on their tour bus. The rappers were all tired and jet-lagged. Then there was the moment when everyone was asleep. I sat there with some of the biggest rappers of the day and realised how weird and cool this was – Big Daddy Kane and others, all fast asleep. So after I photographed them at their gig, I took the chance to capture them asleep. The first lady and biggest mouth in hip-hop, Roxanne Shanté, was still in her outfit, wearing her jewellery. She sucked her thumb like a lot of humans do when they sleep – no matter what age, it’s a comfort thing. She still looks like a hip-hop queen, just showing her human side.

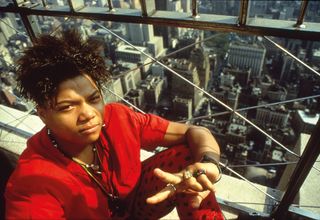

Normski captured the American rapper and actress Queen Latifah at the Empire State Building in New York (Image credit: Normski)

Talking about your new book, Man With The Golden Shutter, what does this publication mean to you?

As a photographer, the idea of creating something that will outlive us still makes me pinch myself. I had my work exhibited in established houses and museums to celebrate black British and hip-hop culture, but this book is probably better than anything. I’ve had my work featured in a few books before, but they were other people’s books, not mine.

I wanted to represent all of my work in a classy way, showcasing both the hip-hop culture and the crazy street stars. To be honest, some of my best pictures don’t even feature famous people. I wanted the book to treat each contact like a print so it’s visually clear for the viewer. I did this all before the era of Photoshop, creating photograms, multi-printing and montages, all in the darkroom by hand. These images deserve quality – and the publisher, ACC Art Books, has smashed it out of the ballpark. The entire team was amazing and supported me throughout the process, otherwise, I would have missed out on quite a bit by trying to do it all myself.

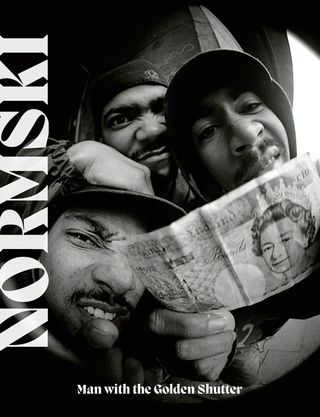

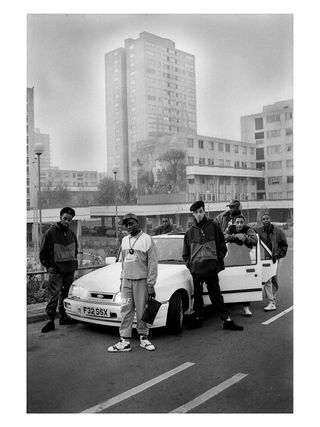

“Taken in 1989, these guys were the epitome of raggamuffin style” (Image credit: Normski)

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.