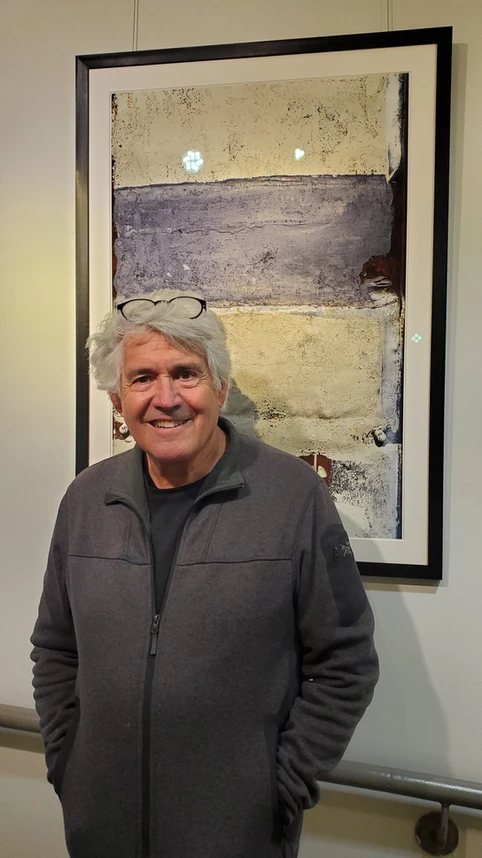

Artist Tad Kline has been on both sides of the track, in the most literal sense of the phrase.

In the 1970s, Kline worked as a brakeman on the Colorado and Southern Railroad Road (now the BNSF), working long hours while moving freight across the Great Plains.

Now Kline spends most of his time on the side of a railroad spur outside of downtown Boulder, camera in hand, documenting graffiti on rail cars as they roll through town.

While some people see graffiti as vandalism, others see art. Kline sees a bit of both.

For the past eight years, Kline has dedicated himself to capturing the transient nature of railroad cars — and how for some, the cars act as a type of permeable canvas.

Kline’s exhibition, “Rolling Steel Canvases,” on display at the Boulder Public Library’s main branch, documents the same stretch of railroad over eight years, depicting how weather, overpainting and removal create an ongoing cycle of creation and alteration in graffiti. His work also examines the thin line between street art and the destruction of property.

“Rolling Steel Canvases” can be seen at the Boulder Public Library on the Arapahoe Ramp, which is on display until Jan. 30. We caught up with Kline to talk about his experiences working for the railroad, his journey as an artist and the evolution of graffiti over the years.

Q: Tad, could you share with us what initially drew you to the specific railroad spur in Boulder for your project “Rolling Steel Canvases?”

A: A long time ago, I used to work as a journalist and did a lot of photography then. I quit all that, and had a life doing other things, but then got back into photography, I realized that I really didn’t know anything about color. I started looking around for something to shoot that was colorful, and the railroad spur is just sitting there, it’s across from one of the Naropa campuses.

I used to work as a brakeman on the railroad, and I wandered out there one day and started taking photos. It kind of became a study in painting, really. I’m a big fan of abstract expressionism and the various other movements of 20th-century painting, and I started to find echoes of that on the boxcars.

It’s become this big project, and I now have well over 100 photos.

Q: Can you tell us a bit about your days as a brakeman?

A: It was kind of a classic industrial, blue-collar job. I worked both as a switchman and a brakeman, and the switchman works in the yard shuffling the deck of boxcars so that a train will come in from one place, and a train will come in from another, and you send the boxcars in different directions. The brakeman is the person on the ground who does the running around and coupling and uncoupling, and stuff like that.

In the summer, it was the best job in the world — some days I would just sit on the engine and we would ride 100 miles across the prairie. In the winter, it was 10 below, and you had to be able to carry a 60-pound hunk of steel several miles to repair a separated train.

It was kind of a Jekyll and Hyde situation, sometimes it was fabulous, and sometimes it was icy cold, hard and a bit dangerous.

Q: What was railroad graffiti like in the 1970s?

A: There was very little graffiti. The tagging or tagger style of graffiti just hadn’t arisen yet. But there was a little bit of what people called hobo graffiti, which was just like a small scrawl on the side of boxcars, usually with a date. But the big colorful tags that you see today hadn’t been developed.

Q: Did you observe anything surprising or encounter any challenges while capturing the graffiti over the eight years of this project?

A: It was really interesting because I was able to see how our paint interacts with the world, out in the weather and exposed to the elements. These tags are outside 24/7, 365, and the sun beats on them, the rain beats on them and the railroad company comes along and scrapes part of them away.

Q: How do you navigate this complex relationship between art and vandalism in your photography, and what conversations do you hope to spark about art in public spaces?

A: I’m not a personal fan of tagging, but it’s a pervasive reality. The photographs focus a lot on the interplay between the boxcar itself and the industrial symbols on the boxcar, and the way that they are affected by the graffiti. But I’m also really fascinated by the painting — not the result as much as the technique, and what happens to the painting over time. The boxcar companies are often trying to undo the work of the taggers, and I show that interplay between the railroad and the graffiti writer in my work.

It truly is public art, but I think a lot of the public would rather not have graffiti. And I guess I’m a realist — graffiti is out there, and sometimes there is a lot of bad graffiti. And the taggers have their own systems of hierarchy and quality control. Sometimes taggers will paint out someone’s graffiti because it’s crappy.

There’s a lot of nice street murals and street art in Boulder, too, but that’s not what’s happening here. Graffiti has to be seen a little bit differently from street murals and street art. But I think that tension shows up in my pictures.

Tad Kline will host an exhibition reception and presentation showcasing “Rolling Steel Canvases” from 5-6:45 p.m. on Tuesday in the Boulder Creek Room at Boulder Public Library. Guests can also request informal gallery tours from Kline. For more information visit TadKline.com.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.