Did you know that France is the second largest market for rap albums in the world? In fact, some French artists sell more units than their American counterparts. However, Americans know hardly anything about French hip-hop. I hope to do my part to remedy this here by exploring the genre of French rap and its impact on French society.

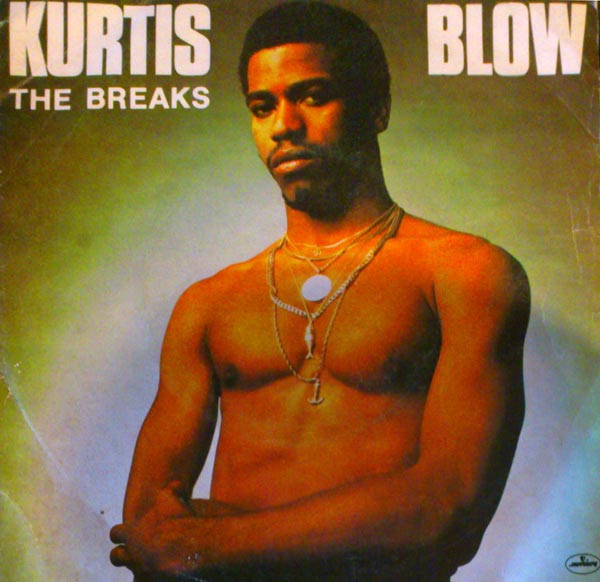

To preface, the rap genre was born in New York City in the early 1970s by young DJs at block parties. These artists isolated and spoke over the percussive and instrumental breaks of popular funk and disco music. It reached mass commercial success in the late ’70s with the release of The Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight” (1979) and Kurtis Blow’s “The Breaks” (1980). When compared to the complex multisyllabic rhyme schemes of later rappers like The Notorious B.I.G. and MF DOOM, these early songs were relatively simple. However, they paved the way for the success of the art form in America and abroad. For a more in-depth discussion of the intricacies of rap music and the genre’s evolution in the U.S., I suggest watching the video by Vox titled “Rapping, deconstructed: The best rhymers of all time.”

In America, Black artists and culture dominate rap culture. In France, however, the socio-cultural categories that rap fits into are different and slightly broader than in America. There, rap is less based on race, and more based on the artist’s place and culture of origin. The southern city of Marseille, and Saint-Denis, a suburb of Paris, are the French equivalents of New York, Atlanta, or Los Angeles when it comes to rap and hip-hop.

Many French rappers hail from countries in North and West Africa that were historically French colonies. In fact, France’s North African colonial empire formed the largest block of immigrants to France, with more immigrants to France from Morocco and Algeria than any other country in 2023. These countries, along with Tunisia, Libia, and Mauritania, are collectively referred to as the “Maghreb.” Because of France’s geographic proximity to continental Africa, Afro-French rap artists incorporate the language and musical styles of their countries of origin into their music to a far greater degree than American artists. This concept, or the “music of the home country,” is referred to as “Bled.”

On the whole, Black hip-hop culture in America is much more removed from its African heritage. For one, the first enslaved Africans were brought to America 400 years ago. Comparatively, many French hip-hop artists are first- or second-generation immigrants, so Bled would remain an integral part of their identity and appear in the music they create. Due to America’s history of enslavement and cultural assimilation, many African-American musical traditions evolved separately from their African roots. Musical style imitates life. In other words, artists’ class, culture, and identity influence the creation of musical genres. This aforementioned closeness of the immigrant experience and the modern legacy of colonialism remain core components of French rap. Despite artists incorporating musical elements, languages, and cultures from across Africa, the Caribbean, and the Middle East into their music, rap has unified these disparate cultural roots to create one complex genre.

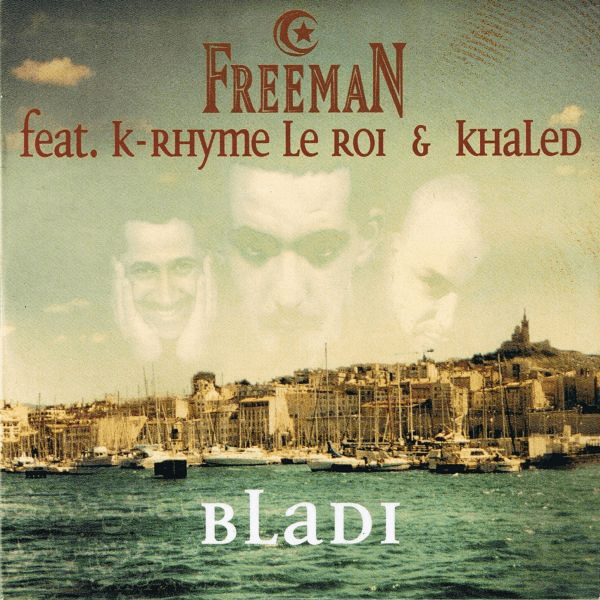

A perfect example of this syncretism is the song “Bladi” (1999) by Freeman ft. Khaled and K-Rhyme le Roi from their album “Palais de Justice”. “Bladi” merges “Rai” (North African Arabic pop) with hip-hop beats to create a striking French-Arabic soundtrack backed by distinctly Arab instrumentals and vocals provided by Khaled. Dense with meaning, Khaled longs for the Bled of the home country: Algeria, a country torn apart by the Algerian War and subsequent internal struggles during the 50s and 60s.

This era would remain a source of shame for France and a burden to Algerians who experienced and passed these events down to the future generation. Lyrics like “I left it’s not my fault, only an hour plane flight separates us…it is not that I cannot, but that I don’t want to go” speaks to the guilt of leaving their home country for a better life in France. The song continues “I dream to see [Algeria] in good health, what glory to be a country without people torn apart,” to the chorus of the song, “Is this the price of liberty? With a forgotten liberty with its slaughters, the Bled to rot.” This is a particularly mournful and evocative vision of the immigrant experience, and its multilingual nature requires fluency in French, French slang (le verlan), and Algerian Arabic to fully understand the song’s meaning. This ensures an audience that is not only French but has similar life experience to the singer.

Another song that touches on a similar aspect of the immigrant experience is “Maghrébin” (2017) by Hornet la Frappe. Maghrébin refers to a person from the Maghréb countries. Here, Hornet speaks to the vibrant life and pride of the “young Maghrébin who will not be chained” with “the bronze color of the landscape, there are millions of us, Maghrébin Maghrébin, the times are hard I stand strong I am Maghrébin, I lack everything, I deny myself nothing, I am Maghrébin.”

The song grapples with heritage, race, and identity. It’s especially notable in its difficult relationship with the French “laïcité,” or the citizen. Part of the French Constitution, the concept refers to the separation of church, state, and freedom of religion for all citizens. In the modern era, however, it represents a French national identity based upon ill-defined “French values.” The laïcité can impose a monolithic view of French civic values on an increasingly diverse society. This broad definition has recently limited “religious” expressions and questioned the “Frenchness” of, primarily, Muslim immigrants. Therefore, rap songs that emphasize a combination of identities where the Bled becomes a distinct part of the individual’s “Frenchness, rather than being subsumed by it, presents a challenge to current politicized discourse surrounding French national identity.

Perhaps French rap can be more overtly political than American rap. Many rappers directly reference issues from the socio-political grievances of their local communities to the legacy of global colonialism. This is not to say that American rap is apolitical, but rather, it stylistically approaches these ideas more subtly. Kendrick Lamar’s Super Bowl halftime show was filled with political references and messages, from his opening line to Samuel L. Jackson playing a Black “Uncle Sam,” but he conveyed his commentary through metaphors. Compare Lamar’s performance to the track “Young people of the world” from alter-globalist, Argentinian-French rapper Keny Arkana’s 2006 album “Entre ciment et belle étoile.” Arkana calls out the capitalist system, the global military-industrial complex, and the abandonment of the Third World, calling for “resistance at the time of neoliberalism and its wars.”

In 2024, after the far-right National Rally won 34% of the vote in French parliamentary elections, a group of 20 rappers released a ten-minute video titled “No Pasarán” (an anti-fascist slogan meaning “They shall not pass”). In the video, they attack various political figures, call to vote against Marine le Pen and the far-right, and proclaim, “Palestine from the Seine to the Jordan”. Marine le Pen has personally feuded with various rap artists for years (including the award-winning group PNL), adding this video to her long series of attacks. She successfully led a national campaign of public outcry to remove the rap song “Write my name in blue” by Youssoupha. The song was the French soccer team’s anthem for the 2021 European championship, and le Pen condemned it as “insulting” and “anti-French.” Another battle fought in the ongoing culture war in the West.

French rap is a unique sub-genre of the global hip-hop movement that is often mistakenly overlooked by music listeners and cultural scholars. You shouldn’t let the language barrier prevent you from experiencing, and grappling, with another culture’s ideas. After all, I’m sharing messages in a college newspaper on the other side of the world.

Did you know that France is the second largest market for rap albums in the world? In fact, some French artists sell more units than their American counterparts. However, Americans know hardly anything about French hip-hop. I hope to do my part to remedy this here by exploring the genre of French rap and its impact on French society.

To preface, the rap genre was born in New York City in the early 1970s by young DJs at block parties. These artists isolated and spoke over the percussive and instrumental breaks of popular funk and disco music. It reached mass commercial success in the late ’70s with the release of The Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight” (1979) and Kurtis Blow’s “The Breaks” (1980). When compared to the complex multisyllabic rhyme schemes of later rappers like The Notorious B.I.G. and MF DOOM, these early songs were relatively simple. However, they paved the way for the success of the art form in America and abroad. For a more in-depth discussion of the intricacies of rap music and the genre’s evolution in the U.S., I suggest watching the video by Vox titled “Rapping, deconstructed: The best rhymers of all time.”

In America, Black artists and culture dominate rap culture. In France, however, the socio-cultural categories that rap fits into are different and slightly broader than in America. There, rap is less based on race, and more based on the artist’s place and culture of origin. The southern city of Marseille, and Saint-Denis, a suburb of Paris, are the French equivalents of New York, Atlanta, or Los Angeles when it comes to rap and hip-hop.

Many French rappers hail from countries in North and West Africa that were historically French colonies. In fact, France’s North African colonial empire formed the largest block of immigrants to France, with more immigrants to France from Morocco and Algeria than any other country in 2023. These countries, along with Tunisia, Libia, and Mauritania, are collectively referred to as the “Maghreb.” Because of France’s geographic proximity to continental Africa, Afro-French rap artists incorporate the language and musical styles of their countries of origin into their music to a far greater degree than American artists. This concept, or the “music of the home country,” is referred to as “Bled.”

On the whole, Black hip-hop culture in America is much more removed from its African heritage. For one, the first enslaved Africans were brought to America 400 years ago. Comparatively, many French hip-hop artists are first or second generation immigrants, so Bled would remain an integral part of their identity and appear in the music they create. Due to America’s history of enslavement and cultural assimilation, many African-American musical traditions evolved separately from their African roots. Musical style imitates life. In other words, artists’ class, culture, and identity influence the creation of musical genres. This aforementioned closeness of the immigrant experience and the modern legacy of colonialism remain core components of French rap. Despite artists incorporating musical elements, languages, and cultures from across Africa, the Caribbean, and the Middle East into their music, rap has unified these disparate cultural roots to create one complex genre.

A perfect example of this syncretism is the song “Bladi” (1999) by Freeman ft. Khaled and K-Rhyme le Roi from their album “Palais de Justice”. “Bladi” merges “Rai” (North African Arabic pop) with hip-hop beats to create a striking French-Arabic soundtrack backed by distinctly Arab instrumentals and vocals provided by Khaled. Dense with meaning, Khaled longs for the Bled of the home country: Algeria, a country torn apart by the Algerian War and subsequent internal struggles during the 50s and 60s.

This era would remain a source of shame for France, and a burden to Algerians who experienced and passed these events down to the future generation. Lyrics like “I left it’s not my fault, only an hour plane flight separates us…it is not that I cannot, but that I don’t want to go” speaks to the guilt of leaving their home country for a better life in France. The song continues “I dream to see [Algeria] in good health, what glory to be a country without people torn apart,” to the chorus of the song, “Is this the price of liberty? With a forgotten liberty with its slaughters, the Bled to rot.” This is a particularly mournful and evocative vision of the immigrant experience, and its multilingual nature requires fluency in French, French slang (le verlan), and Algerian Arabic to fully understand the song’s meaning. This ensures an audience that is not only French, but has similar life experience to the singer.

Another song that touches on a similar aspect of the immigrant experience is “Maghrébin” (2017) by Hornet la Frappe. Maghrébin refers to a person from the Maghréb countries. Here, Hornet speaks to the vibrant life and pride of the “young Maghrébin who will not be chained” with “the bronze color of the landscape, there are millions of us, Maghrébin Maghrébin, the times are hard I stand strong I am Maghrébin, I lack everything, I deny myself nothing, I am Maghrébin.”

The song grapples with heritage, race, and identity. It’s especially notable in its difficult relationship with the French “laïcité,” or the citizen. Part of the French Constitution, the concept refers to the separation of church, state, and freedom of religion to all citizens. In the modern era, however, it represents a French national identity based upon ill-defined “French values.” The laïcité can impose a monolithic view of French civic values on an increasingly diverse society. This broad definition has recently limited “religious” expressions, and questioned the “Frenchness” of, primarily, Muslim immigrants. Therefore, rap songs that emphasize a combination of identities where the Bled becomes a distinct part of the individual’s “Frenchness,, rather than being subsumed by it, presents a challenge to current politicized discourse surrounding French national identity.

Perhaps French rap can be more overtly political than American rap. Many rappers directly reference issues from the socio-political grievances of their local communities to the legacy of global colonialism. This is not to say that American rap is apolitical, but rather, it stylistically approaches these ideas more subtly. Kendrick Lamar’s Super Bowl halftime show was filled with political references and messages, from his opening line to Samuel L. Jackson playing a Black “Uncle Sam,” but he conveyed his commentary through metaphors. Compare Lamar’s performance to the track “Young people of the world” from alter-globalist, Argentinian-French rapper Keny Arkana’s 2006 album “Entre ciment et belle étoile.” Arkana calls out the capitalist system, the global military-industrial complex, and the abandonment of the Third World, calling for “resistance at the time of neoliberalism and its wars.”

In 2024, after the far right National Rally won 34% of the vote in French parliamentary elections, a group of 20 rappers released a ten minute video titled “No Pasarán” (an anti-fascist slogan meaning “They shall not pass”). In the video, they attack various political figures, call to vote against Marine le Pen and the far-right, and proclaim, “Palestine from the Seine to the Jordan”. Marine le Pen has personally feuded with various rap artists for years (including the award-winning group PNL), adding this video to her long series of attacks. She successfully led a national campaign of public outcry to remove the rap song “Write my name in blue” by Youssoupha. The song was the French soccer team’s anthem for the 2021 European championship, and le Pen condemned it as “insulting” and “anti-French.” Another battle fought in the ongoing culture war in the West.

French rap is a unique sub-genre of the global hip-hop movement that is often mistakenly overlooked by music listeners and cultural scholars. You shouldn’t let the language barrier prevent you from experiencing, and grappling, with another culture’s ideas. After all, I’m sharing messages in a college newspaper on the other side of the world.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.