By Victor Block

People walking along a thoroughfare in Silver Spring, Maryland, just outside of Washington, D.C., pass beneath a line of abstract paintings attached to the side of a building. Each includes a quote attributed to a famous historic figure.

“Be tolerant with others and strict with yourself,” instructs Marcus Aurelius, the stoic philosopher and Roman emperor from 161 to 180. “Do not judge a nation by how it treats its highest citizens but its less fortunate ones,” implores Nelson Mandela, the anti-apartheid activist who went on to become the first president of South Africa.

These images are examples of street art, which is displayed in public places throughout the country and transforms various platforms — buildings, pavements, trains, subway cars and other visible surfaces — into outdoor museums that are accessible to everyone.

What today is an art form had its genesis during the Great Depression, which impacted the Unites States in the late 1930s. A public project was launched to provide jobs for out-of-work painters and sculptors. Their creations were distributed to museums, schools, hospitals and other public institutions.

Other early examples of this genre were the “Kilroy Was Here” images that showed up around the world during World War II. They were line drawings of a bald man (sometimes depicted as having a few hairs) with an elongated nose and peering out from behind a fence.

Some U.S. military personnel sketched the picture and text on walls where they were stationed, encamped or visited. A popular tongue-in-cheek claim was that the phrase and image even showed up on enemy-held beachheads where American troops landed.

An increasing wave of graffiti began to show up on outside walls and other surfaces throughout the United States in the 1960s. Much of it consisted of slogans of protest, social commentary or political observations. Since then, these open-air exhibits have evolved into a recognized form of expression throughout the country. In addition to street art, they’re sometimes referred to as independent art, post-graffiti, neo-graffiti and guerilla art, a term that first emerged in the United Kingdom and then spread around the world.

While graffiti artists have used spray paint as their primary medium, what has evolved as street art encompasses a wide range of modes. They include sticker art and stenciling, wood-blocking, rock-balancing and yarn-bombing, which is the use of colorful displays of knitted or crocheted yarn or fiber.

That public art installation in Silver Spring is the work of Tom Block, an artist, author, playwright and founder of the International Human Rights Art Movement, which uses creativity in all its formats to spur social change and seek a world that is more just and welcoming to all.

Titled “Cousins,” it consists of 15 large art and text panels that transform the space into an outdoor gallery. They project the community’s diversity as an asset by emphasizing not only the different cultures in the community but also how they positively interrelate.

Other examples of this art form are scattered throughout the country and are available to people near where they live and in destinations to which they might travel. Galleries in New York City host exhibitions of street artists’ work. Philadelphia and Pittsburgh are among cities that have provided funding to pay street artists to decorate public walls.

Sarasota County, Florida, claims to have public art displays “as abundant as the palm trees,” visible on elevator doors of parking garages, the centers of traffic circles and numerous other venues. Downtown Chicago is home to more than 100 sculptures, mosaics and paintings, including figures created by world-famous artists such as Pablo Picasso and Alexander Calder.

Murals, paintings, sculptures, graffiti and hand-made structures abound through Los Angeles. They are displayed outside of art museums, in Metro stations, on building walls and even in downtown parking lots.

The best-known street artist in the world is Banksy, which is the pseudonym by which an England-based political activist is known, while his real name and identity remain unconfirmed. His satirical witticisms and often stenciled images have appeared on streets, walls, bridges and other surfaces. Some of them have been sold, at times by removing the facade on which they were painted.

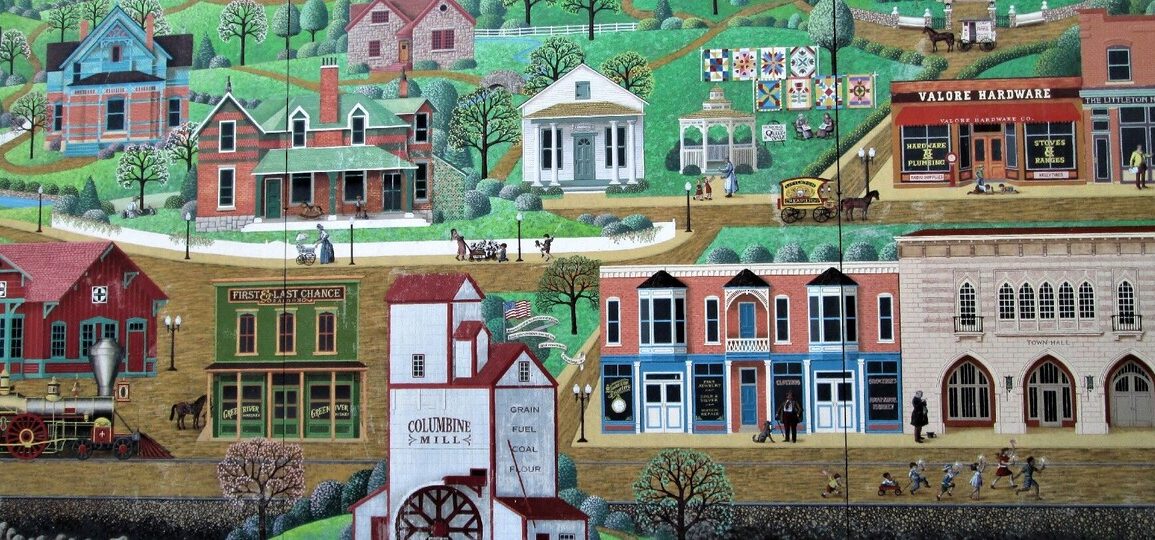

I encountered an outstanding example of street art during a recent visit to Colorado when I arrived at the light-rail station in Littleton, a suburb of Denver. When I stepped off the train, my eyes were immediately drawn to a long, vibrant mural stretching 40 feet and standing 7 feet high.

The colorful painting depicts 50 historic structures, most of which are located near the depot. It provided a meaningful welcome to the town and an introduction to an important but sometimes overlooked aspect of the art world. This is but one example of that town’s art in public places program, which provides funds each year to pay for the installation of murals.

WHEN YOU GO

For more information: streetartutopia.com and silverspringdowntown.com/go/cousins.

Victor Block is a freelance writer. To read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate website at www.creators.com.

This untitled mural greets passengers at the light-rail station in Littleton, Colorado. Photo courtesy of Victor Block.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.