Desmond Clifford

Whatever happened to graffiti? I don’t mean the world of tagging, monikers and wall art. The wall mural, once a Northern Ireland monopoly, has transferred to Wales with attractive effect and brightened up some of our towns.

No, I mean good old-fashioned graffiti of the scribbling kind: “Dez was here”, “Free Wales”, “Dalgleish is god” – that kind of stuff.

At one time there was barely a street sign, bridge or corner of public realm left unsoiled by the black felt tip.

The public guardians thundered against delinquency but graffiti was, surely, a crude antidote to the question of alienation.

You existed if you said you did, and so did your causes. Once, you could learn a lot about a place just by looking at the walls. Today, virtually nothing. Whatever happened?

Graffiti has long antecedents. Archaeologists have discovered some 11,000 examples in Pompeii alone. These include the rather lovely, amorous declaration:

“Health to you, Victoria, and wherever you are, may you sneeze sweetly.”

And the tribute to a dead friend:

“I’m sorry to hear you are dead, and so goodbye!”

And my personal favourite, the very straightforward:

“Gaius Pumidius Diphilus was here”, dated 78 BC.

More recently, Mussolini’s famous dictum appeared on a wall:

“It is better to live one day as a lion than 100 years as a sheep.” Underneath someone wrote:

“Better to live 100 years!”

Splott Bridge

Graffiti was very present in late 20th century Wales. Rhodri Morgan in his memoir describes a youthful instance of political direct action. In the late 1940s, “Nye for Prye” was daubed onto Splott Bridge in Cardiff (in other words: “Aneurin Bevan for Prime Minister”, a reasonable assertion at the time).

By the late 1960s, British Rail painted over the bridge. Rhodri was horrified, “This was sacrilege. It was the Checkpoint Charlie, the main point of entry into the Independent Socialist Republic of Splott.”

In the middle of the night Comrade Rhodri, accompanied by his wife Julie, now a Senedd Member, returned and repainted the call for the now deceased Bevan to be made PM.

Apparently the graffiti remained for a further 25 years, perhaps until residents asked, “who the hell is Nye?”

I remember drives around rural Wales where motorists were invited to remember Llewelyn Our Last Prince and Owain Glyndwr. He, and others, were forecast to Rise Again.

At one time in my life, I drove regularly between Aberystwyth and Newtown past the large rock on which “ELVIS” was painted, an astonishing cultural assertion when you think about it.

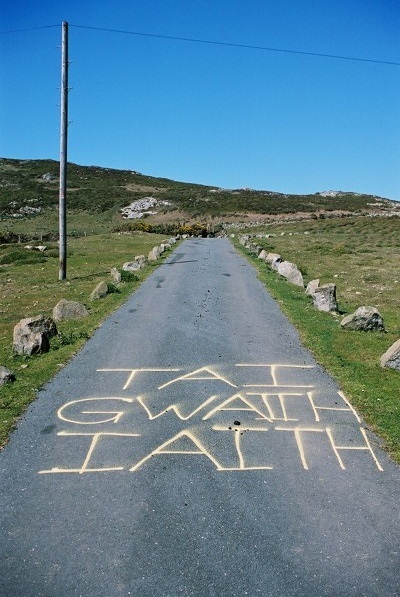

The CND symbol was widely copied, as was the dragon’s tongue symbol of Cymdeithas yr Iaith/ the Welsh Language Society.

A mop and bucket crew were on permanent standby outside the Welsh Office in 1970s/80s Cardiff.

Then there was a 1990s fad for the sinister-looking anarchist symbol of the capital A inside a circle.

Meic Stephens

“Cofiwch Dryweryn” is the most famous Welsh political graffiti of our times. The original slogan was painted by Meic Stephens and his friend Rodric Evans on a wall near Llanrhystud in 1962/3 according to his memoir.

Tryweryn was the drowned village which lived on as a symbol of Wales’ inability to protect itself through legitimate political means, an inability corrected (partially, at least) by devolution.

Meic and Rodric’s graffiti became permanent and is now reproduced on badges, mugs and T-shirts.

“Cofiwch Dryweryn” is as redolent of a time in Wales as Keith Haring’s babies were on the New York subways.

That was the public form of graffiti, designed to convey a propaganda message to the world at large. Then there was the more individual version.

Keegan is King, Peter 4 Mary etc.

We scribbled over schoolbags, walls, street signs, advertising hoardings.

Anything that could be written upon, was written upon and thus we persuaded ourselves that we and our views mattered, or at least existed.

It made for an ugly public realm for a few decades.

Actually, it was a fitting phenomenon for the years of Wales’s industrial decline. Barely a sign could be erected without being despoiled by graffiti. Whole streets and shopping centres were rendered even uglier by the primitive urge to leave our mark.

Art

Eventually graffiti began to mutate into a proper art form, aided by the irrelevance of what modern art museums were offering.

Beginning in 1970s New York, graffiti artists began colonising public spaces. Some of their work is amazing. Jean-Michel Basquiat broke through spectacularly into the money-art world while Keith Haring unleashed a whole new approach to public art.

Nearer home, Banksy delighted a generation and makes us smile, which contemporary art manages all too rarely.

Ordinary old-fashioned graffiti has been in retreat. The evidence of my own eyes tells me it has largely disappeared from towns and suburbs, buses and trains.

What changed? The ubiquitous spread of CCTV and high vis security guards probably has something to do with it but it’s the Internet, surely, which is decisive.

Who wants to scrawl on the wall when this awesome power to project is available?

Some 500 million tweets are sent every day while 500 hours of video are loaded onto YouTube every minute.

Everyone can be a model, a philosopher, entertainer, raconteur.

The Internet comprises a number of words beyond our comprehension – a google, in fact.

This article adds another thousand to the never-ending Babel.

We should not be nostalgic for ugliness. Most graffiti was ugly and much of it mean-spirited. And unlike the Internet, you could hardly avoid it even if you wanted to.

Apparently, the cloud is storing the collected digital output of humankind.

This is amazing but when the record is so vast, I wonder if anything individual will truly survive?

Doesn’t posterity need a kind of selection to be meaningful?

Our friend from Pompeii, Gaius Pumidius Diphilus wrote the least original graffiti of all time, but it’s still there. And so, in a sense, is he.

Support our Nation today

For the price of a cup of coffee a month you can help us create an

independent, not-for-profit, national news service for the people of Wales, by

the people of Wales.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.