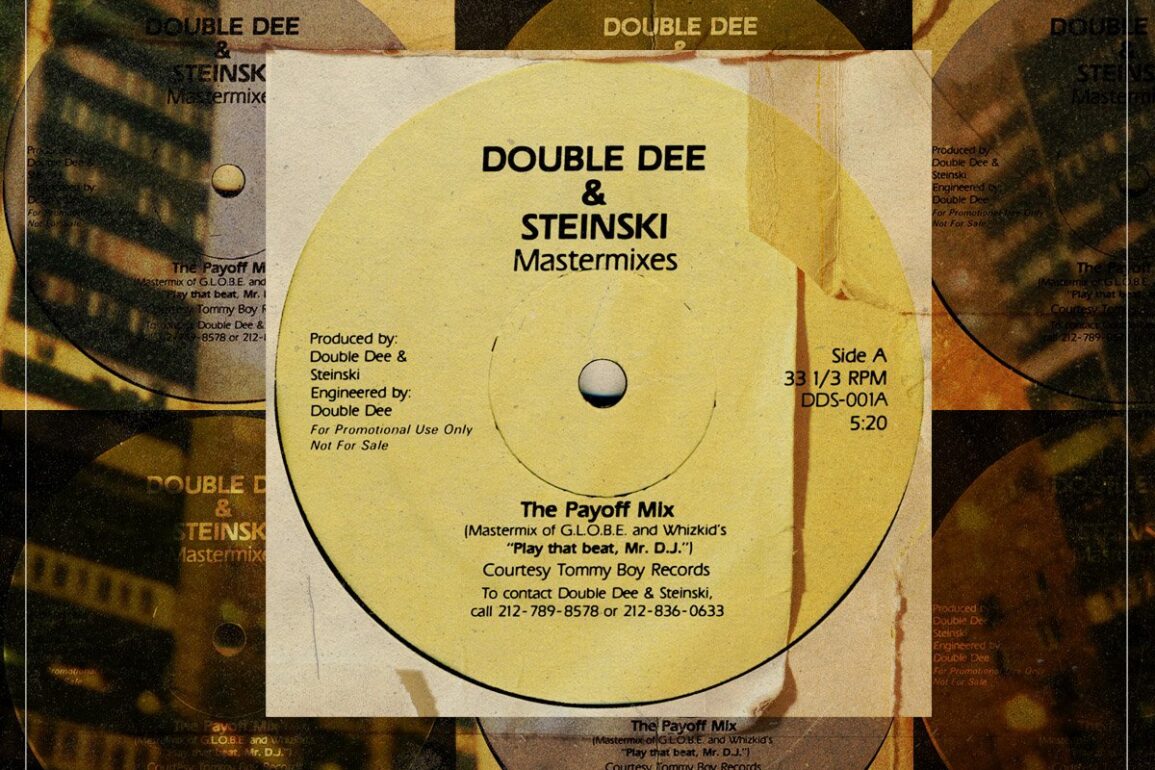

(Credits: Far Out / Double Dee and Steinski)

Today, DJs and producers are celebrated for their sampling prowess and creative deep-dive into their record collection, Kanye West’s or MF Doom’s rich excavation of unorthodox beats and expanding hip-hop’s sonic references, the mark of a bold artistic vision that they’re praised for. Back in the infancy of hip-hop, however, sampling was a wild west practice mired in ethical questions of copyright and fair use that waged long into the 1990s.

In 1983, New York’s Tommy Boy Records hosted a promotional contest, challenging budding DJs to remix G.L.O.B.E. and Whiz Kid’s ‘Play That Beat, Mr DJ’ and boasting Afrika Bambaataa, Shep Pettibone, and ‘Jellybean’ Benitez on the jury.

Up for the glory, Doug DiFranco and Steven Stein, under the aliases Double Dee and Steinski, stitched together their entry ‘Lesson One – The Payoff Mix’, a dense mosaic of inventive samples jumping between James Brown, Kurtis Blow, Yazoo, and even Humphrey Bogart. Winning first prize, Double Dee and Steinski were gifted with a cool $100, a Tommy Boy shirt, and, crucially, airplay and club distribution for their mix.

“What we did,” Steinski told NPR in 2008, “Was construct a five-minute piece completely out of other pieces, without any sort of narrative other than what we were able to stitch out of the pieces. We used a whole lot of samples — we didn’t use one; we used 60 or 70, I think, in the first record. And that was probably among the first approaches like that, even though, of course, now that I think about it, it was all tape. It wasn’t digital technology; it was tape and razor blades.”

Inspired by the novelty ‘break-in’ records Bill Buchanan and Dickie Goodman featuring comedic sketches and audio interruptions of popular records of the era, sampling didn’t appear to be so unprecedented in the music industry.

When digital technology made this practice much easier, following Flying Saucer Records’ comedy LPs seemed natural: “All of a sudden, you could be referential by taking the thing itself. Instead of re-contextualizing it on your instrument in music as part of your own composition, you could then re-contextualize the piece by taking the actual piece and putting it in a new setting. It’s always had questionable legality from the beginning, but its utility and ease is not a question.”

‘Lesson One’ and its several follow-ups hit copyright snags. While massive on the underground club circuit, stores couldn’t sell the mixes, and there was barely any easy avenue in clearing rights. Following disputes with De La Soul’s and Beastie Boys’ sampling cherrypicking in the late 1980s, a system was set up, but it was costly: “It turned into, ‘Now you can’t clear it, because it’s wildly and prohibitively expensive… So only rich people can play. There is now a mechanism: If you can afford it, then definitely you’re online. But it’s strictly for basically one major label talking to another major label.”

Double Dee and Steinski have become lauded among turntablist sample stitchers like Coldcut, DJ Shadow, and The Avalanches, and the pair are still busy on their Bandcamp and even cutting the long-awaited ‘Lesson Four’ in 2018.

“The truth of the matter is, the legality of this doesn’t really make any difference to me,” Steinski concluded. “I mean, I’m gonna make the records no matter what. It’s like saying, ‘If you use that colour blue in your painting, that’s not legal.’ Well, what does that have to do with anything? It would be great if it was legal, it’s too bad it’s not, and so what?”

[embedded content]

Related Topics

Subscribe To The Far Out Newsletter

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.