“Make something of yourself, have your own story”

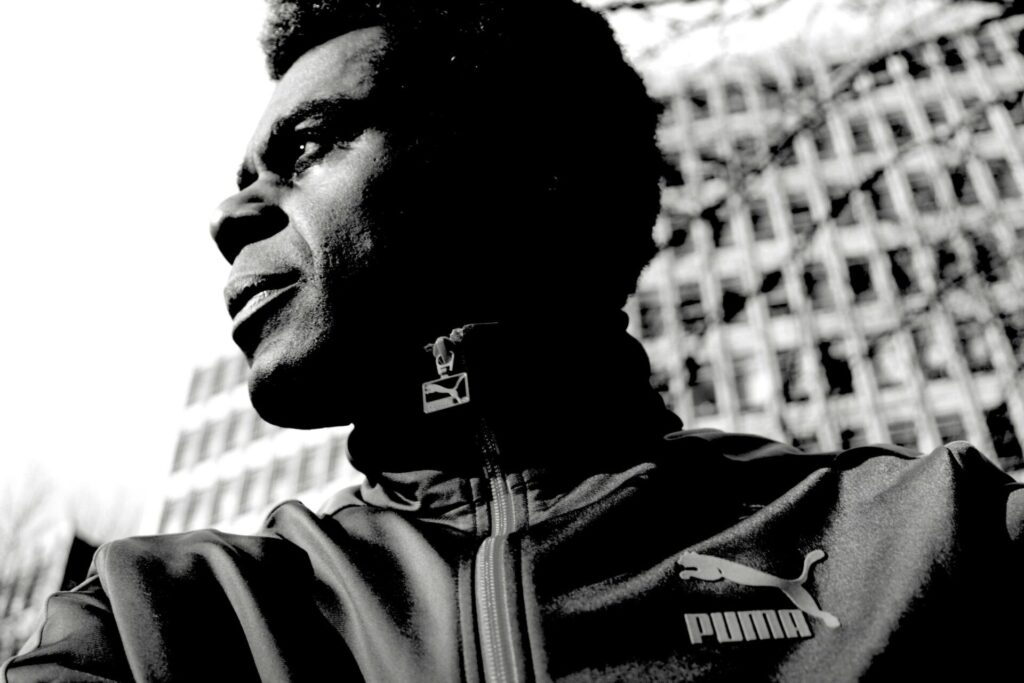

I met Normski at his flat in Victoria Park, East London. Well into his sixth decade, some grey hairs might sprout around his sideburns and from beneath his navy blue beanie hat. But he’s lost none of the youthful energy that made him one of the most recognisable figures from the hip-hop and dance music scenes of the late 80s to the mid-90s. He speaks at a million miles per minute, barely finishing one idea before bouncing onto another.

He grew up in Kilburn in a second-generation Jamaican household where extended family would often come and stay while finding their feet in their new home. There would be “Singing, church, and stuff like that. I was born with music, to be fair.” He adds, “The kind of people I’ve grown up around have all had character, which was very much drummed into you. Make something of yourself, have your own story.”

Normski paints a picture of a fairly idyllic existence, comfortable with his dual Jamaican-English existence growing up in the seventies. As kids do, he tried out a bunch of different hobbies, from building model trainsets to riding BMX through to various instruments, before discovering a camera. He soon graduated from taking photos at ‘summer fetes’ to the jazz clubs of Soho. At one point, he shows me a stunning motion print of the saxophonist Wayne Shorter he took for The Wire magazine in the early 80s; “I was in the vicinity, being this cool, young Black photographer, wanting to be a photographer for the love of actual photography.”

But he fell deep for hip-hop. “Forever, American TV was the fucking Brady Bunch, and then we started seeing programmes with Black kids on them.” He name-checks the films “Wild Style and Beat Street, the coolest movie.” He also points to the “the post-punk people. Vivienne Westwood, and Malcolm McLaren, and they have that connection with Blondie and [Fab 5] Freddie in New York.” As disparate influences, ushering in the new; “They’re like the rebels of their time who tune into the rebels of the next time.”

In hip-hop, Normski found “A new subject that I totally related to.” But at the first few live shows, he admits to being shy around artists who would often clam up at the sight of a camera, “There was an awful lot of looking and wondering what to take pictures of.” With time, his confidence grew along with his camera skills, eventually garnering him the nickname: ‘The man with the golden shutter’.

Fashion played a big part in projecting his louder-than-life persona; a style he described to me as “Rudeboy sort of English-centric clothing, with Italian designer leather.” He soon caught the attention of broadcaster and journalist Janet Street-Porter.

From 1988 to 1994, Normski was one of the hosts of DEF II, a BBC2 magazine show for Gen X produced by Street-Porter that aired innovative comedies like Red Dwarf alongside US imports like Ren & Stimpy, Fresh Prince Of Bel-Air and Wayne’s World sketches.

Normski explains the concept behind DEF II was to, “Break new ground and boundaries in television broadcasting.” It would give the audience “The definitive form of how television, particularly for young people, should look.”

But the undisputed jewel in the DEF II crown was Dance Energy. Filmed in Manchester, the magazine format show would “feature different elements of the scene, the fashion, the club scenes, and people doing cool stuff.” The ‘cool stuff’ would be anything from segments on the sneaker brand wars in the US through to Frankfurt’s gay club scene to the legendary live performances from rap and rave acts, including Naughty By Nature and The Prodigy in their first live TV performance, which required an epilepsy warning. The show was a huge success, connecting with as many as one million people per week, going well beyond the intended audience of teenagers.

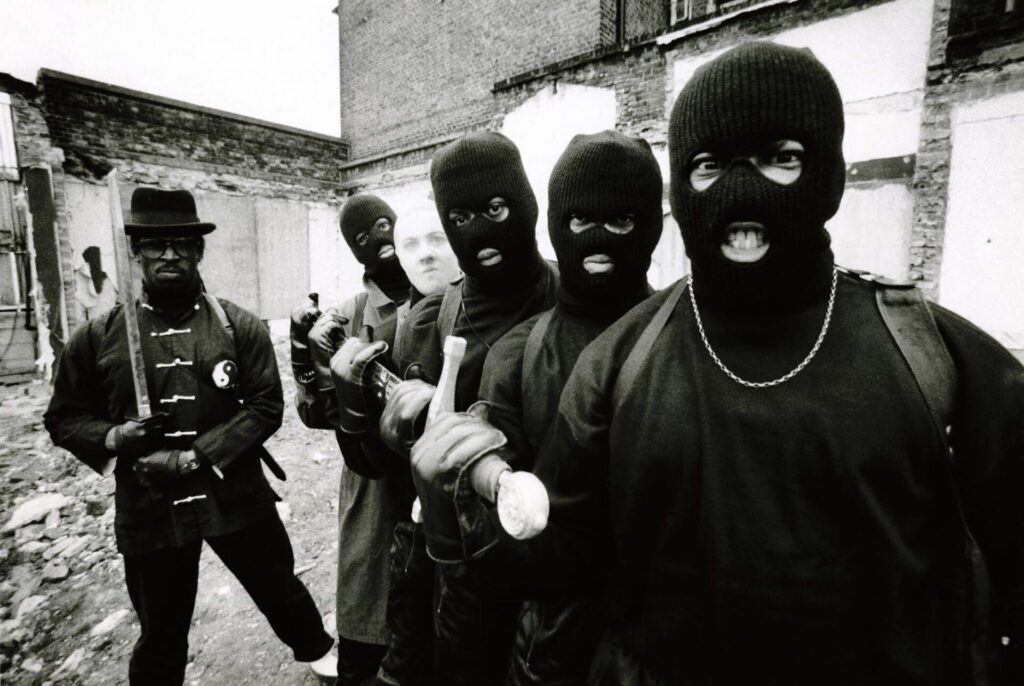

The show was chaotic and edgy in a natural way. Often, this led to tense, last-minute negotiations between headstrong artists and the show’s producers. Normski remembers an appearance by Hijack, a “very controversial UK hip-hop group on the edge of censorship regarding how they went about themselves. Wearing bulletproof vests and the whole balaclava look. The BBC authorities couldn’t handle that.” Showing violence or sexism was non-negotiable, and everyone dancing in the audience seemed to be having the time of their lives.

And at the beating heart of it was Normski, whether it be his improv raps connecting segments or his cutting Style Police observations from the streets of the UK, Normski was on a mission to bulldoze a space for hip-hop in the mainstream without compromising on the culture. Ultimately, the show’s success would prove its undoing as many musicians wanted to perform on Dance Energy rather than saccharine prime-time of BBC1’s Top of the Pops. His work on the show was highly prescient; now we live in a world where people ‘curate’ culture with a few clicks of a button for their fashion archive accounts on Instagram, but Normski put in the hard graft to create culture. Thirty years later, Normski still gets stopped by people across the country who fondly remember the show.

Normski photographed some of the biggest names in hip-hop alongside his work on television, but he was committed to helping the local scene thrive. He provided many first-generation UK rappers with a distinctive visual identity. Among them were the group Cookie Crew, MC Remedee (Debbie Pryce) and Susie Q (Susan Banfield), two vital female voices in the first decade of UK hip-hop. Cookie Crew formed in 1983, winning a national rap championship at the Wag Club. The friends from Clapham, South London, steadily built up their reputation, from recording studio sessions with John Peel to touring with Afrika Bambaattaa. In 1988, they had an unexpected hit with ‘Rok da House’, where they appeared as guest vocalists on the single by production trio the Beatmasters. The song peaked at number 5 in the UK charts and is often described as the first-ever hip-house track.

Although they never performed the song live, Susie later admits, “We were very adamant that they would not associate us with the track.” Cookie Crew felt the song was unfaithful to their hip-hop roots, creating an inaccurate portrayal when rappers in the UK were still finding their identity. However, it didn’t stop them from releasing two albums and collaborating on music with Gangstarr and Stetsasonic in the States. Like many of Cookie Crews’ peers, their vocal delivery had an American tone, but the content of their message was distinctly Black British, with all three singles from their debut album Born This Way (released on London Records, 1989); ‘Born This Way (Let’s Dance)’, ‘Black Is The Word’, and ‘From The South’ in particular paying homage to their South London home.

They were also passionate about the wider issues facing Black people, regularly performing at anti-apartheid gigs and releasing music alongside other UK rappers as B.R.O.T.H.E.R (Black Rhyme Organisation To Help Equal Rights), where all the artists’ royalties were donated to the African National Congress (ANC).

Speaking with the author Arusa Qureshi, in her discerning book Flip the Script: How Women Came To Rule Hip-Hop, Susie explains that the Cookie Crew’s time in America was often spent educating folk, “A lot of the people we met didn’t realise that there were actually Black people in England… We were educating them on who we were, British, but British Caribbean too.”

Born This Way was recorded in New York, and Cookie Crew were among the first UK rappers to try and break the US, although this didn’t go down well with fans or critics back home. As Susie later explained, “There was a lot of jealousy and bickering on the scene and talk about staying true to the game. But for us, we were officially a business. We’d given up our day jobs and went to New York to learn from them about the whole creative industry.”

The Cookie Crew released their second and last album, Fade to Black, in 1991. The duo cited the pressure from their record label to conform to pop stereotypes as the reason they stopped releasing new music as the Cookie Crew. Debbie and Susie continue to work in the music industry today, leaning on their experience to educate others, particularly Black female artists, to push through the barriers of misogyny in the music industry.

Britcore, Music of Life and the first generation of UK rappers

Thanks to his collaboration with Simon Harris’ Music Of Life label, Normski went beyond photography to creative direction. This included collaborating with the dashing Derek B, who parlayed his DJ residency at the Wag Club (notorious for its selective door policy) into being the first poster-boy of UK rap, achieving major chart success with ‘Good Groove’ and ‘Bad Young Brother’ (both released in 1988), and being the first English rapper to appear on Top of the Pops an achievement all the more remarkable as hip-hop (nevermind ‘UK hip-hop’) was being dismissed as a passing fad at best.

MC Duke probably had the most striking aesthetic of that generation; the baritone-voiced MC’s music merged murky sci-fi atmospherics and proto-rave synths (he would later release music as I.C.3. on the Shut Up And Dance label) with old funk and dialogue samples from Roots: The Gift the film that told the story of the fictional slave character Kunta Kinte.

His debut album, Organised Rhyme, featured a regal-looking Duke wearing a three-piece tweed suit, flat hat, walking cane, and a vast gold medallion. “African gentleman” is how Normski describes the look, adding, “He looked fabulous. A lot of the artists in the early days were very culture-conscious, and that came across in the attire.”

When I ask Normski for his most memorable shoot, he’s unequivocal, “Hijack. Probably because they were dressed in full SAS style, carrying a six-foot samurai sword. We climbed over this wall in a derelict area near Brixton, and the police came by.” Normski’s “heart raced,” but he convinced them the sword was just a prop for a record cover photo, adding, “It’s because of the end result as well. The photograph is really powerful.”

What Do You Call It? From Grassroots to the Golden Era of UK Rap by David Kane is published by Velocity Press

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.