There is a plague on the streets of my city, and yours. Festering on corners where buildings meet, scattered over end gables and electricity boxes, distantly visible in the darkest alleyways. What started as a few isolated examples has recently exploded into an epidemic. I’m not talking about rats or discarded Lime Bikes. This is much more sinister.

What I’m talking about is street art. I don’t mean graffiti, which is little more than vandalism. What I mean by street art is the ubiquitous brightly coloured murals created in public spaces by individuals who are funded by local councils. Every British city is now rife with these garish creations, childish paintings designed to illicit a response amounting to the lowest common denominator of artistic interpretation: “oh that’s interesting”.

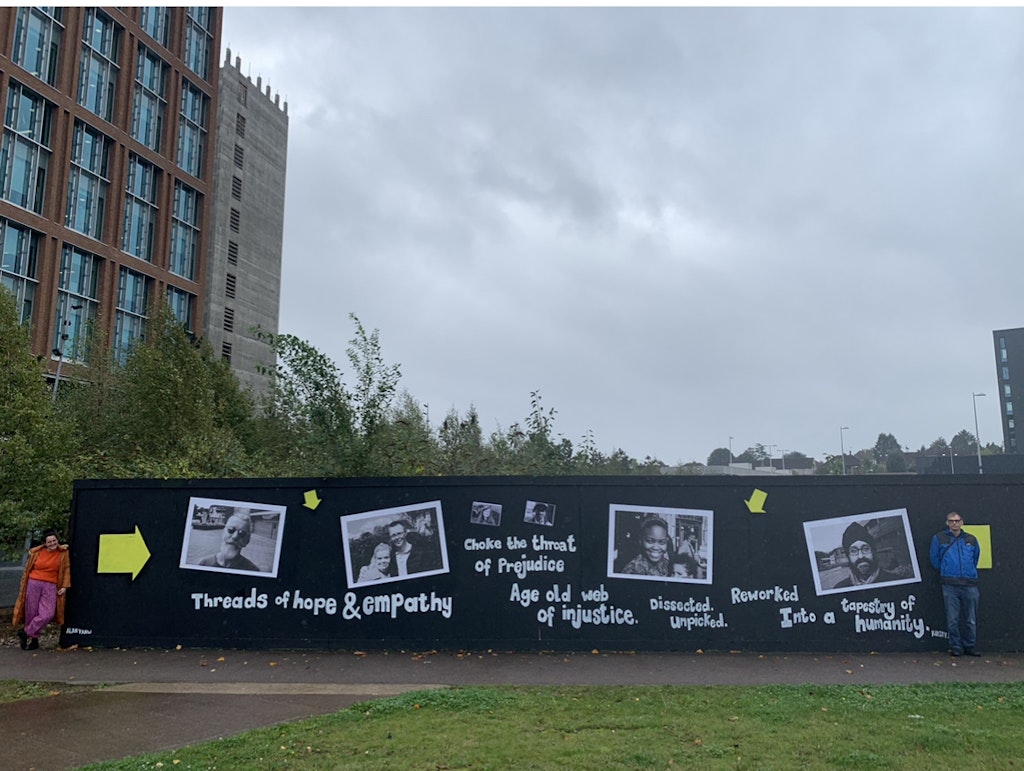

These artworks — I use the term loosely — are almost always brightly coloured, luridly so, and often depict a generic urban scene, animal, flower, or person, or a combination of all of the above. There is seldom any meaning to the artwork beyond “symbolising the vibrant culture of the street” or “highlighting the rich diversity of the local area”. These paintings exist for only one reason, contrary to claims that they improve the street or bring in additional investment into local businesses: they simply exist to cover up ugly things.

You never see street art on a beautiful Georgian facade; murals don’t often get placed onto beautiful architecture or on well-regarded streets. It is the local council equivalent of putting lipstick on a pig, and they are making you pay for it. Not only do councils fund this through council tax and business rates, but through something called Business Improvement Districts (BIDs).

You can pay a fee for someone to walk you through the most decrepit areas of a city

These districts are areas where businesses within said area have voted in favour of collective investment to improve or regenerate the area in which they operate. Once businesses in the area vote in favour of establishing a BID, all businesses in that area are then subject to a further levy which is used for these urban facelift procedures. The BID organisation proposes plans to businesses, who are allowed to offer their input and choose (to an extent) what the organisation will do with their money.

This often results in things which are quite good and useful, and which local government should be doing anyway: planting more trees along streets, ensuring litter is removed and discouraged, clearing weeds from flower planters. But more frequently, it has resulted in gigantic gaudy cartoons springing up on every available space on the walls of businesses.

What makes this even worse is that some cities and districts are so bereft of ideas to make up their city’s “culture” that they latch on to street art as a defining characteristic of their vibrant, inclusive community. The problem is that everywhere is doing the same thing.

Thrifty individuals and organisations now offer “street art walking tours’ to unsuspecting tourists (usually from America) who think this is a unique part of this quaint little island story. From Newcastle to Shoreditch, Bristol to Belfast, you can pay a fee for someone to walk you through the most dreary and decrepit areas of a city of your choosing, talking to you in a tone barely audible over traffic and police sirens about how a fifty foot long painting of a hummingbird is relevant to this city’s industrial past. In Belfast, several tours of this kind operate, with the cost rarely being under £10 per person.

Also in Belfast is the Ulster Museum, home to artworks ranging from Rembrandt to Renoir, and many renowned Irish artists such as John Lavery and Jack Yeats. The museum also has an impressive selection of temporary exhibitions which pop up in its many galleries; not long ago I was able to see Caravaggio’s The Supper at Emmaus and The Taking of Christ here.

If you prefer more contemporary, unorthodox art, then you could visit the Metropolitan Arts Centre, which has regular temporary exhibitions in its several galleries and boasts a quite pleasant cafe in the centre of the city’s Cathedral Quarter. Both of these spaces are free to visit, and the artworks contained within are of a much higher quality than anything found on the street. It is often said that contemporary art is just juxtaposition, that there is no other underlying meaning other than X differs from Y and so I shall create XY; street art falls into this category too. But contemporary art also has another characteristic: hypocrisy.

We are so often told that the buildings which are erected in our towns and cities are cool, modern, functional. We’re told that the sleek concrete-and-render designs are similar to other buildings which have won awards overseas. We’re told that brutalism is good, actually, and that we are simply stuck in our ways, the low-status philistines who would prefer pastiche and imitation than our own, modern style. If this were so, and these buildings were as lovely as people say, then why does the government feel the need to cover them up in bright colours and parade them as little more than blank canvases?

Hypocrisy and juxtaposition, then, are what we get. The local governments seem wont to have their cake, eat it, and give us back the excreted remnants, all the whilst charging us for the pleasure. This is democracy manifest. When independent local businesses are already being squeezed for cash, with bills and rates increasing by sums unheard of in previous years, gaslighting these businesses into believing that street art is the way to increase their revenue is distasteful and simply untrue. Regeneration requires more than paint and promises.

Enjoying The Critic online? It’s even better in print

Try five issues of Britain’s most civilised magazine for £10

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.