If there is one exhibition in New York City that I would recommend everyone see before it closes, it is The Way I See It: Selections from the KAWS Collection at the Drawing Center. KAWS (born Brian Donnelly) is ubiquitous — my barbershop sells figurines of his demented Mickey Mouse with X’d out eyes, as do shops around the world. He is the only artist whose works can be bought by teenagers, multimillionaires, and people getting their hair cut. For those in the art world who don’t look at auction sales, The KAWS ALBUM (2005) — a mash-up of characters from The Simpsons and the album artwork for Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band by The Beatles — sold in Hong Kong for $14.8 million.

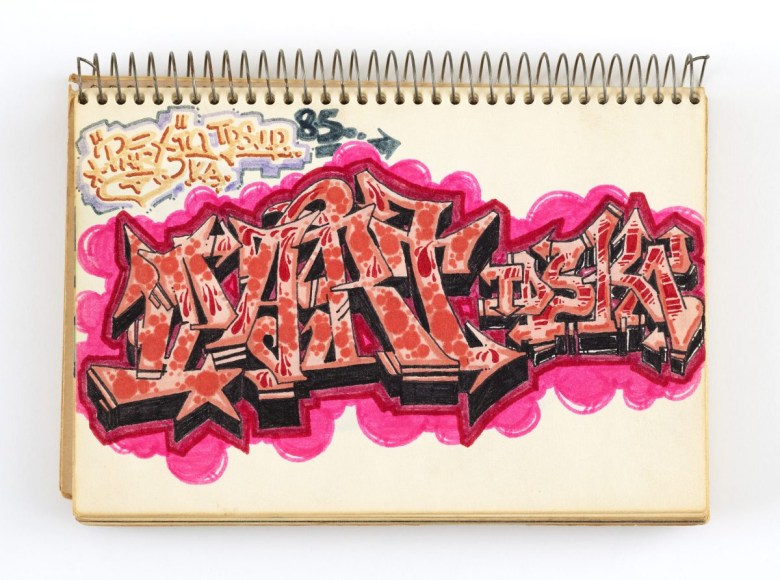

I don’t care about his pedigree, though, because KAWS buys art by the boatload. This exhibition features more than 350 works on paper, plus paintings, sculptures, and furniture, selected from a collection of 4,000 pieces. I am not talking about big, shiny blue-chip art objects; KAWS buys drawings by artists of every stripe, from Pablo Picasso, Willem de Kooning, and Ed Ruscha to Susan Te Kahurangi King, Helen Rae, and William A. Hall, to sketchbooks by graffiti artists (Dondi, CRASH, and Rammellzee), which he began trading his work for when he was a graffiti artist.

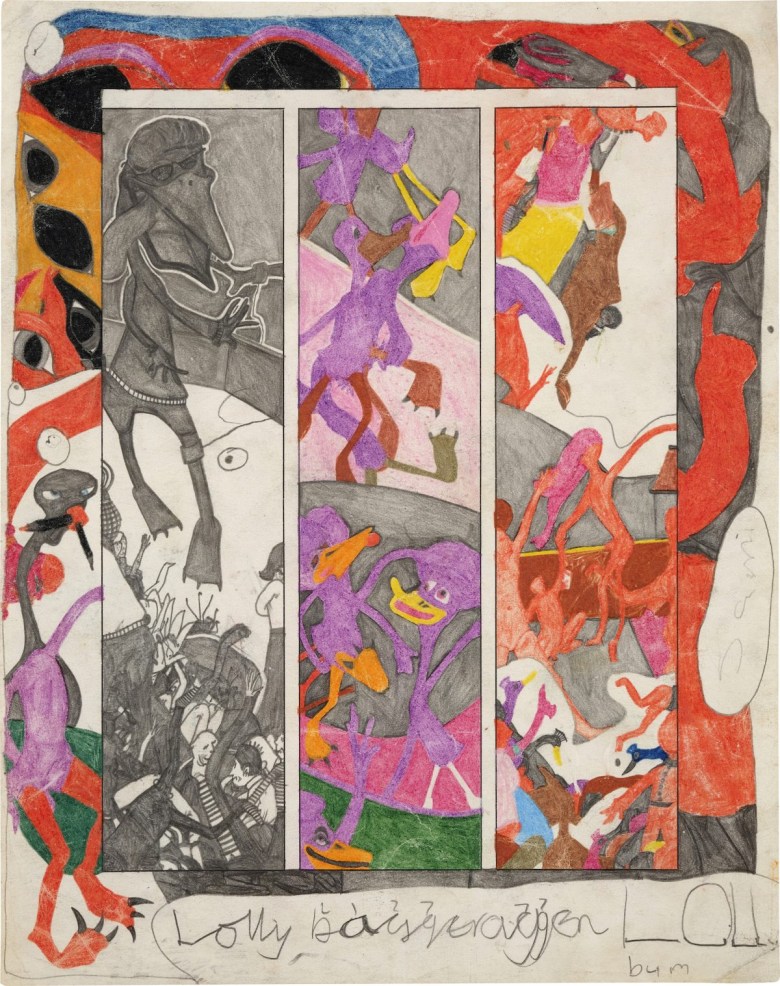

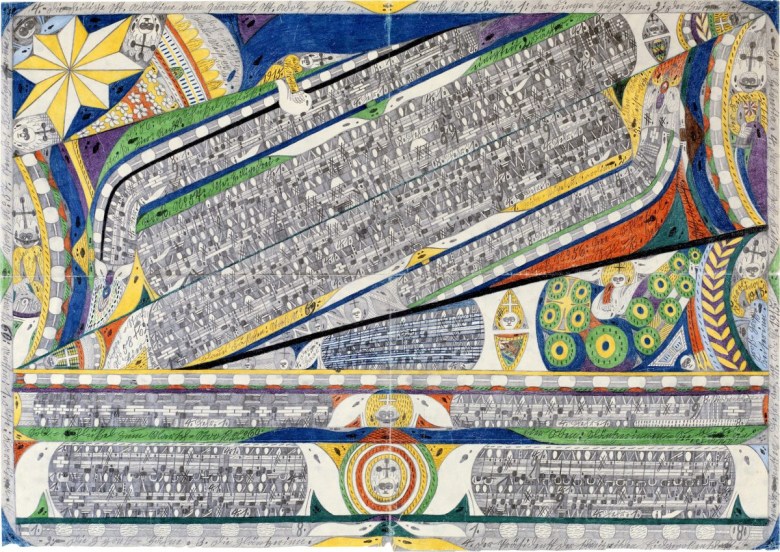

This breakdown of hierarchies goes well beyond that of any exhibition I have seen previously. The show includes drawings by the comic artist Basil Wolverton, who had printed on his stationery, “Producer of preposterous pictures of peculiar people who prowl this perplexing planet”; the repetitive, claustrophobic work of Martín Ramírez, an impoverished laborer who was diagnosed with schizophrenia and institutionalized for much of his adult life; and fashion magazine-inspired drawings of Helen Rae, who was deaf and nonverbal. She began making drawings at the age of 52 at the First Street Gallery and Art Center, an art studio designed specifically for adults with developmental disabilities.

KAWS describes the thread connecting these works together as “People making marks.” Well, that seems true of nearly everyone, but many of the artists in the artist’s collection were obsessed with mark making to the point that it overtook their lives. Several made art with no ambition to exhibit or receive any recompense. They did it because they were compelled to do it.

A well-known statement by Philip Guston, who credited it originally to John Cage, came to my mind: “When you start working, everybody is in your studio — the past, your friends, enemies, the art world, and above all your own ideas — all are there.” While both artists seem haunted, it is not clear who was in the room with Henry Darger or Nicole Appel, whose colored pencil drawings of labels and printed matter are among the many highlights of this extraordinary show. What we know of their ideas is in their work, which, for all of its graphic clarity, can feel remote.

This is not the case with the drawings of Jim Nutt, Peter Saul, Tomoo Gokita, Dana Schutz, Gladys Nilsson, H.C. Westermann, and Anton van Dalen, whose work combines humor and empathy. Who would have thought that Lee Lozano’s charcoal portraits would bring to mind the drawings and prints of Käthe Kollwitz? Empathy is one of the things separating them from the work of KAWS himself and artists in the show such as George Condo. While the latter two are graphically fluid, their art does not emanate empathy toward their subjects. I did not expect to consider the role empathy might play in these works, especially when thinking about the dark humor of Westermann, but after spending some time with them, it became inescapable. This is what infuses certain works with gravity, while its absence makes other works feel empty.

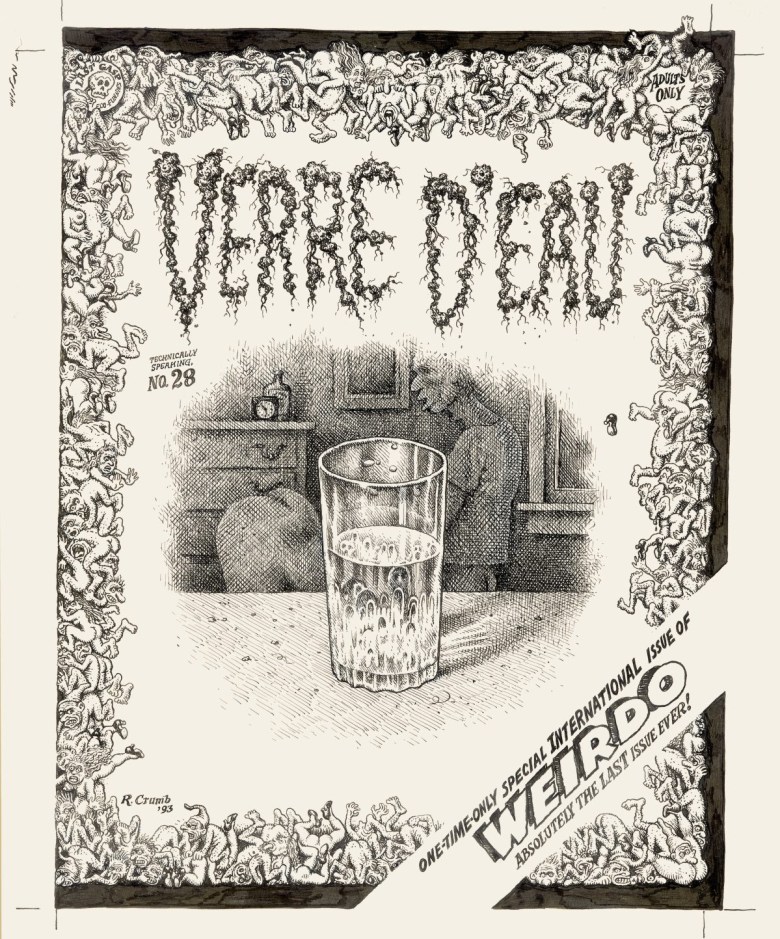

Also on view is a large selection of diaristic comic strips by R. Crumb and Aline Kominsky-Crumb, sketchbooks by taggers such as Dondi (Donald Joseph White) and CRASH (John Matos), early pen and ink drawing of skeletons by Judith Linhares, and drawings populated by a mélange of characters from anime, manga, and Japanese monster movies by Yuichiro Ukai. KAWS’s eclectic, discerning eye is dazzling. At the end of this year, I am sure that The Way I See It will be on my top 10 list of 2025’s best art exhibitions.

The Way I See It: Selections from the KAWS Collection continues at the Drawing Center (35 Wooster Street, Soho, Manhattan) through January 19. The exhibition was curated by KAWS.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.