In 1989 six young British graffiti artists – Rough, Part2, Stormboy, System, Tee Roc and Solo1 – joined a groundbreaking new collective by Juice 126, to form “a graffiti crew but not a graffiti crew”. Guided by Juice’s manifesto ‘rebel against the rebellion’ to gain collective artistic freedom, the group sought to break free from the traditional constraints of graffiti, and forge a new path as a ‘post-graffiti supergroup’ that were free to explore their own artistic dreams and ambitions.

A new book from Remi Rough explores the legacy of that renegade UK graffiti artist collective know as Ikonoklast Movement. Below we talk to Remi about Ikonoklast and the book.

What was the original vision behind the Ikonoklast Movement, and how did Juice 126’s manifesto shape its direction?

Juice’s vision—which became all of ours—was to break free from the rigid rules of traditional graffiti and push the boundaries of experimentation within the scene. Despite graffiti being a rebellious art form, it had developed its own strict codes, and we wanted to challenge that. The manifesto gave us clear direction. What still amazes me is how Juice found and brought us together in a pre-digital age—it took real effort, constant travel, and a shared trajectory that naturally pulled us into orbit with one another. I often wonder where I’d be without them.

How did the Ikonoklasts redefine graffiti art in the 1990s?

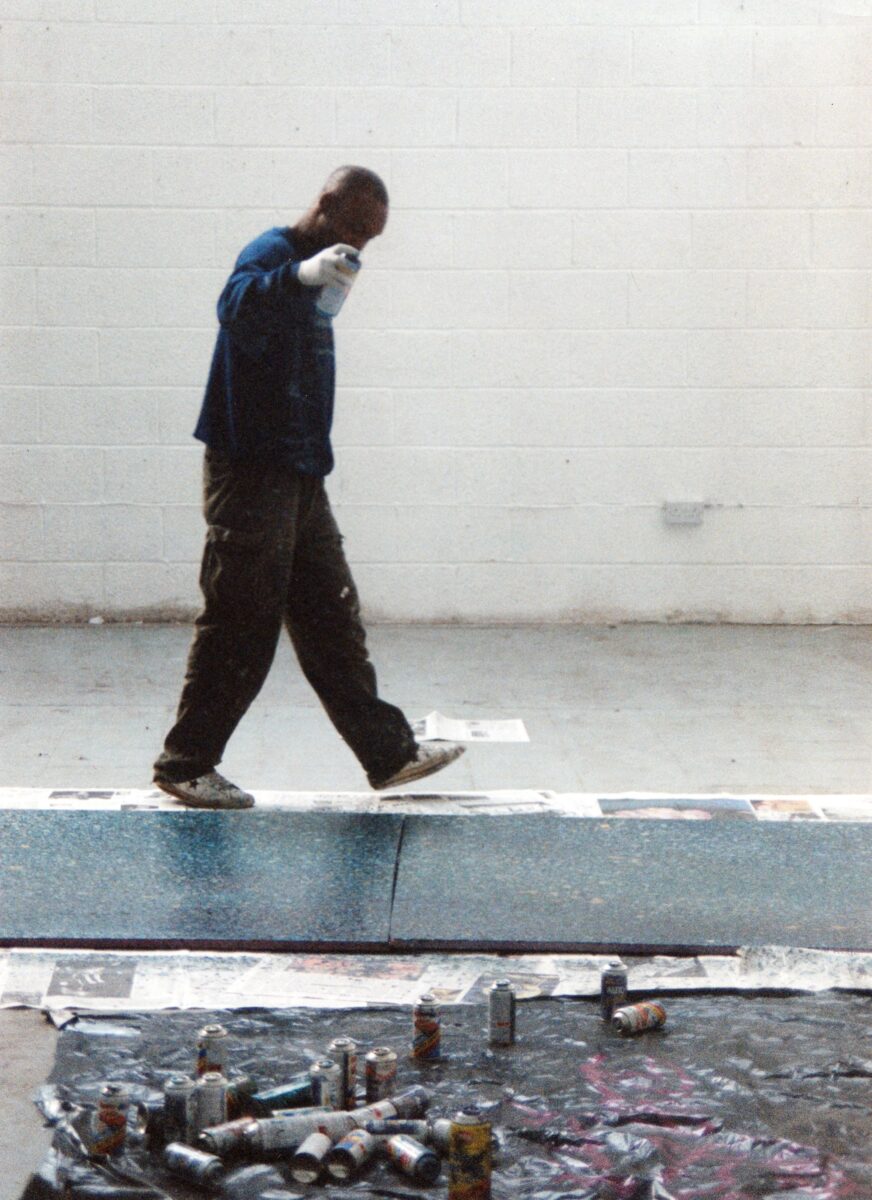

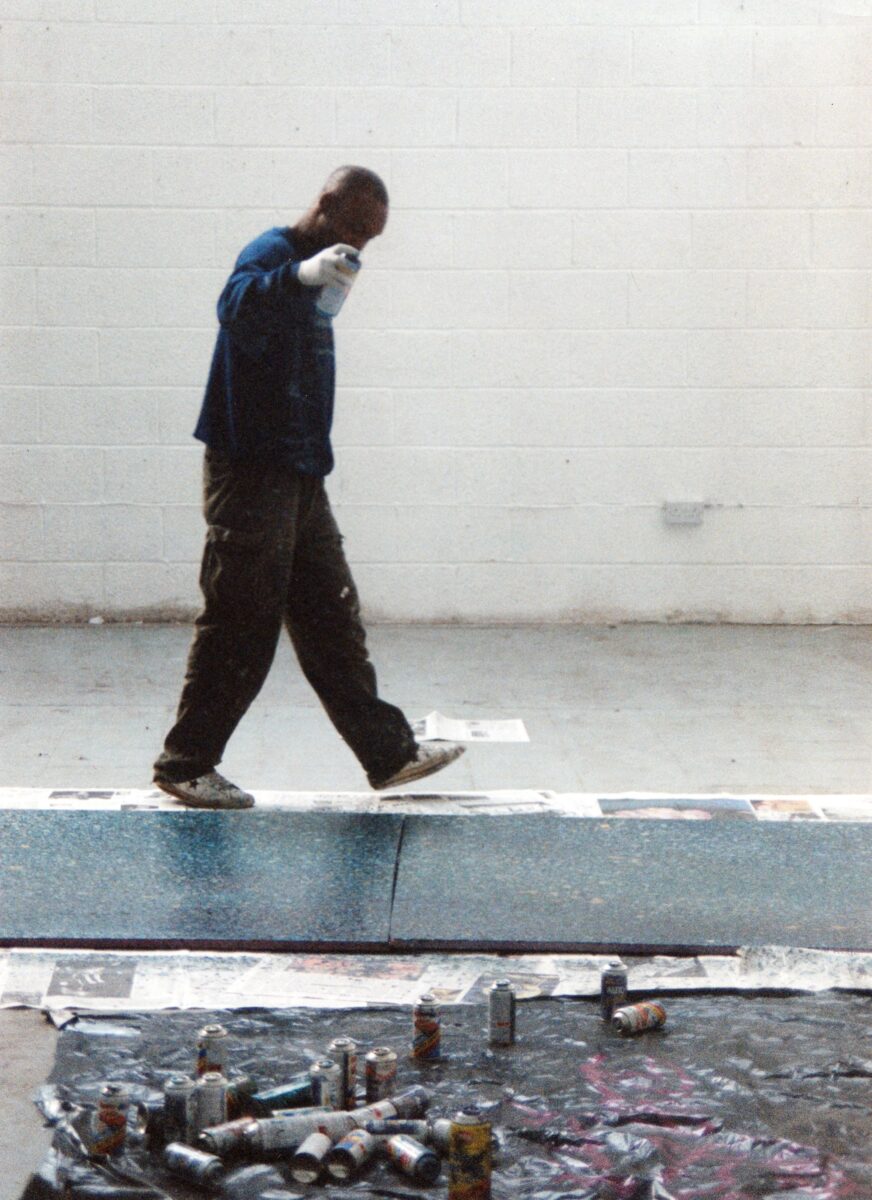

We set a new standard early on, holding major exhibitions of aerosol art a full decade before it became common in the UK. While France and the Netherlands were also active, we were ahead of the curve here. We stripped away ego and worked as a collective, which gave us the freedom to truly experiment. Juice pioneered spray paint mixing—almost unheard of at the time—creating vibrant new palettes from dull car paint. Today’s 300-shade spray ranges didn’t exist back then; we worked with what we had and still pushed the form forward.

What role did collaboration play in the group’s evolution, and how did individual styles coexist within the collective?

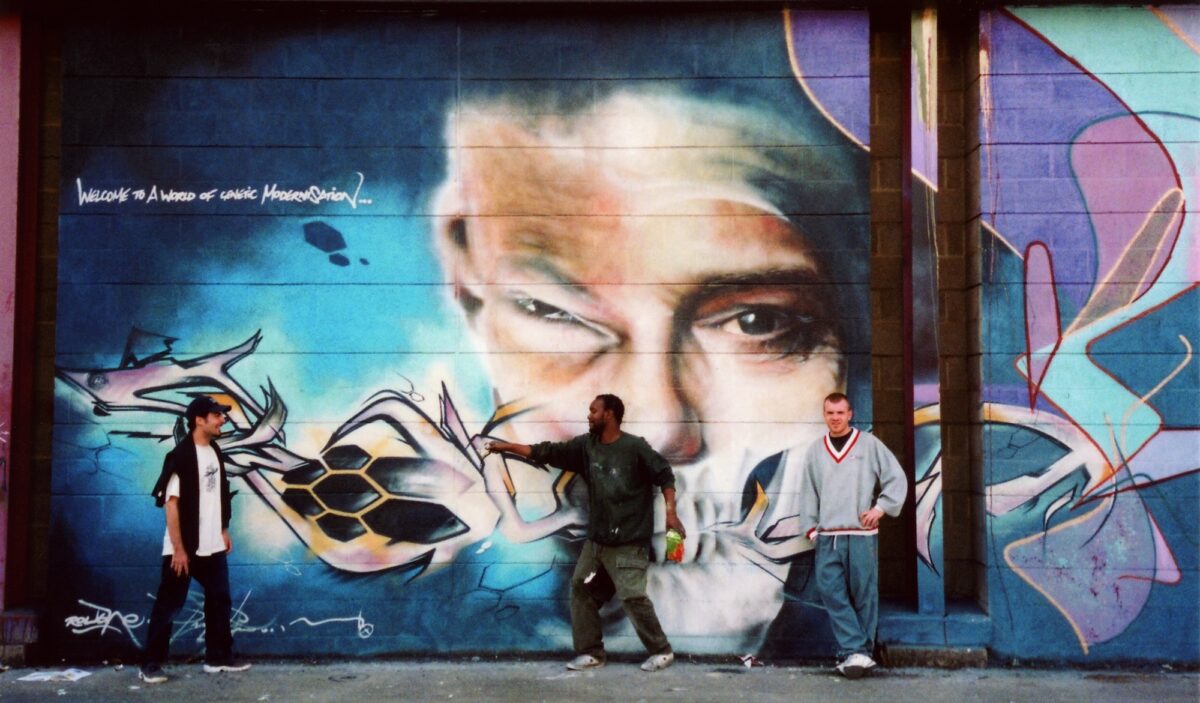

Collaboration was fundamental. We constantly aimed to go bigger and more detailed. A peak moment came in 1998 with our “Welcome to a World of Genetic Modernisation” wall in Hull—despite different styles, we had total trust in each other. While we each painted solo in our respective hometowns, the collective effort required serious commitment: long journeys, coordinating places to stay, sourcing paint. It wasn’t easy, but we made it happen. Part 2 and System pioneered photorealism with car paint; Stormboy brought in figurative abstraction; Chu was making his paintings literally 3 dimensional and handing out 3D glasses to passers by; Solo One and myself were experimenting with letters beyond the recognised norm; Juice was literally pouring litres of paint down the side of Birmingham buildings. It was a time of fearless experimentation and idea-sharing.

Why has so much of the Ikonoklast legacy remained undocumented until now?Life took over—children, families, mortgages, careers. Despite that, we stayed connected over the years and remain close to this day, apart from Tee Roc, who sadly passed away in 2005. We continued painting, organising events and exhibitions, but the Ikonoklast legacy gradually faded into the background. It wasn’t until about a year ago that Part 2 approached me to help curate a show on Fleet Street in London—essentially reuniting most of the crew. Around the same time, my friend and fellow artist Kid Acne had been persistently encouraging me to archive our work or make a documentary. His push was pivotal in sparking the idea for this book.

Everyone contributed what they could—writing, photos, scans, old flyers, background info. The response was overwhelming. Simon Armstrong from Tate agreed to write the foreword, being well-acquainted with our story, and art historian Lois Oliver generously contributed a written piece. Greg Hilty from Lisson Gallery also helped out, sharing valuable details from 1980s exhibitions that helped shape some of the book’s historical context. At first, I saw this as a film project—but I realised that starting with the book would give me a solid foundation, a blueprint for the documentary to follow.

Why is now the right time to publish Future Language of the Ikonoklast—and what does the book hope to contribute to the wider conversation about graffiti and contemporary art?

There’s never really a “right” time—it’s simply that now is the time. Most of us are in our 50s and still working full-time as artists. This is a story that’s been overlooked for too long. When a major graffiti and street art show took place in London in 2023 without a single mention of the Ikonoklast Movement, it was clear something needed to be addressed. Our story is real—none of it embellished—and the book includes over 400 images that document our journey.

In terms of the broader conversation around graffiti and contemporary art, Ikonoklast fills a crucial gap. For decades, the art world has been wary of graffiti and its practitioners—choosing to sideline us rather than engage. I refuse to let that continue. We built this movement ourselves, without the backing of art schools, institutions, grants, or any formal infrastructure. We did it for ourselves, on our own terms.

We’ve contributed far more than many of today’s trending artists, not just in output but in substance. We educated ourselves—on art history, on technique, on how to evolve as artists. And we’ve never stopped growing, questioning, and adapting. Now is the moment for that legacy to be acknowledged.

How does the book’s design, its size, paper stock, and limited edition details reflect the Ikonoklast ethos?

I’ve poured everything I have into this book, and I hope the strength of the work—and the calibre of the artists—jumps off every page. There are moments in here that feel like buried treasure: raw, rare, and completely unforgettable. It’s easily one of the most extensive archives of its kind, capturing a defining era in graffiti culture. What blows my mind is that we managed to hold onto all of it—photos, negatives, flyers, invites, letters—through decades of movement and change.

The book itself is 282 pages of grit, history, and heart. It’s weighty but accessible, designed to reflect our ethos: honest, unpolished, and driven by a deep belief in sharing and pushing things forward. This isn’t just a book—it’s a time capsule, a manifesto, and a tribute to everything we built from the ground up.

FUTURE LANGUAGE OF THE IKONOKLAST: A Visual History of Ikonoklast Movement by Remi Rough is published on 18th July by Velocity Press priced at £29.00.

The book is available to purchase with a limited edition dust jacket and A2 poster. exclusively available via Velocity Press. The special edition is priced at £34.00.

Launch Event

Celebrate the launch of Future Language of the Ikonoklast by Remi Rough. Featuring a panel of original members Juice 126, System, and Remi Rough as they discuss the genesis, philosophy, and enduring impact of the Ikonoklast Movement along with DJ sets from Charlie Dark, Strictly Kev, A La Fu, Remi Rough and Kwame 4Eye. More info and tickets here.

About

Velocity Press was founded in 2019 by Colin Steven to curate the best writing in electronic music and club culture – with all the care, creativity and community ethos of an independent record label..

Remi Rough makes complexly composed abstract paintings that create a strong sense of visual pleasure for the viewer. His formative years and experiences as a style writer, (or as most people would know it, a graffiti artist), inform his precise, constructed artworks.

He is a key proponent in the graffuturism and post graffiti movements. Rough has been exhibiting his works and painting murals in major cities all over the world for over thirty-five years. In 2021 he was invited by the former professor of perspective; Humphrey Ocean RA to exhibit in the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition. Rough co-curated and exhibited in ‘Next Wave’ at the Fort Wayne Museum of Art in Indiana in 2022. Other Museum shows include The Museo De Bellas Artes in Santander in 2009, The Musée Mohammed VI in Rabat 2016, the Art Science Museum in Singapore in 2018, Straat Museum in Amsterdam in 2022, MOCA London in 2017 and Tate Modern as part of the ‘Street Art’ exhibition programming in 2009. In 2018 he was invited as part of the Art Basel Hong Kong off site programme to design and install a permanent 100-metre-long pedestrian tunnel in Hong Kong’s Quarry Bay MTR station. From his teenage involvement with the only art movement in history created by and taken forward by children, to a global appreciation of his work, he continues to grow his practice.

Categories

Tags

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.