Arts & Culture

The new program overseen by the multi-hyphenate musician, pedagogue, and producer bridges the two worlds of his musical life.

Wendel Patrick’s first memory is actually a dream. It was a recurring dream that he had for years, well into adulthood. It started when he was about 2, maybe even younger. The dream had no people in it. No light. But there was a steady sound—a beat. Something about that beat made Patrick realize he wasn’t alone.

“And then at some point, the rhythm—the thing that was repeating—became more intense and rapid, and then it stopped,” Patrick says. “And there was nobody else. I knew I was by myself.”

When he could find the words, maybe he was 3 or 4 by then, he asked his mother about the dream. She burst into tears.

Years later he would find out that he had a twin who died in childbirth. The twin’s name was…Wendel Patrick Gift.

This all becomes a little less confusing when you learn that Wendel Patrick was born Kevin Gift. For the first part of his life, everyone knew him as Kevin. He studied classical piano and earned a master’s degree in piano performance from Northwestern University School of Music. But he also started experimenting with electronic music, improvisation, and hip-hop. He bought mics and drum kits and samplers.

When he released his first hip-hop album, folks who knew him only from classical music were confused. He felt a need to distinguish the two sides of his musical life. So for the hip-hop persona, he would go by Wendel Patrick, after his brother, whose presence he always intuitively felt. His classical music persona would stay Kevin Gift.

At the time, he didn’t realize how blurred those two identities might become. That he would become a famous hip-hop producer and musician. That he would bridge the two worlds by bringing hip-hop into the hallowed halls of Peabody Institute. And that it would be a very long time before he would play classical piano again.

Another one of his earliest memories involves the piano. He and his family were living in Venezuela. His father was a diplomat, so they moved around a lot. His mother wanted his older sister, Dina, to start taking piano lessons. She brought Dina and Wendel to the studio of a well-known teacher. Young Wendel, then just 4, also played for the teacher, banging on the keyboard with glee.

“I’ll teach the girl but only if I can teach the boy as well,” the teacher said.

And so his musical journey began.

Patrick, now 51, showed an enormous aptitude for classical piano and it was one of the things that grounded him as his family moved from D.C. to Venezuela to Jamaica. Whenever they would stay at a hotel, his mother would make arrangements for her two children to practice the piano in the lobby or the lounge, if they had one. It was a source of continuity and comfort in his life.

But when he was 14, he stopped playing. He was a teenager—he had other interests: sports, girls, popular music, especially hip-hop. He loved Public Enemy and Eric B. & Rakim. A friend turned him onto the reggae-tinged hip-hop of Boogie Down Productions, which he couldn’t get enough of.

“I still loved classical music,” he explains. “But I just didn’t listen to it that much.”

He went to college, undergrad at Emory University. He majored in political science, figuring he’d be a diplomat like his dad, or maybe a lawyer. One day, a girlfriend asked him to play piano. He demurred at first but finally agreed. She was impressed with his talent, but he was stunned. He sounded terrible, at least based on his own high standards. He had assumed the facility would always be there, but he now understood he needed to use it or lose it. It bothered him, more than he expected.

He began studying piano at Emory and realized that music was his true love. He went on to get that master’s in piano performance at Northwestern. But his love for hip-hop was still percolating. It was the ’90s, so you couldn’t record things on a computer. You needed physical equipment. Mics. Recorders. Turntables.

He began experimenting with different electronic and hip-hop sounds, all while studying to become a concert pianist. In 1997, he moved to Baltimore, where his mother was living (she and his father had divorced by then). He got a small, grubby apartment in Mt. Vernon—by far his biggest and most expensive piece of furniture was his Steinway piano.

Then, in 2005, he had just come home from playing a Mozart piano concerto in Bolivia when he realized that his index finger on his left hand felt strange. He figured he just needed rest. He took two weeks off from playing. When he tried again, the finger felt worse—weak, almost like he had no control over it. He went to a clinic that specialized in hand injuries. The doctors asked him to play. Afterwards, the room got very quiet.

“You’re making me nervous,” he said.

The doctors told him he had a nerve condition called focal dystonia. It was the same condition that Peabody’s most famous professor, the pianist Leon Fleisher, had suffered from. It effectively ended Fleisher’s career as a concert pianist.

This was obviously very depressing news—existentially depressing, in some ways. But Wendel Patrick (who was then still only known as Kevin Gift) has the kind of restless creative spirit that can’t be extinguished. He got more involved in photography, a pastime he had picked up while on tour with a band. He started experimenting more with electronic music. He made that first hip-hop album. And Wendel Patrick was born.

“I DON’T THINK HIP-HOP NEEDS ANY VALIDATION OF ANY KIND. THAT’S NOT WHAT THIS IS ABOUT FOR ME AT ALL.”

If you live in Baltimore, you might know Patrick in any number of ways. Maybe you took piano lessons from him at Music & Arts in Timonium or Ellicott City back in the day. Maybe you’ve attended one of his Boom Bap Society concerts—a series of lively, improvised hip-hop jam sessions that he started with his friend, the composer and DJ Erik Spangler, 14 years ago. Maybe you’ve watched the Maryland Public Television series he hosts, Artworks, where he interviews fascinating members of the local arts community. Maybe you’ve listened to his albums or his collaborations with the likes of spoken word artist Ursula Rucker or Baltimore’s own Eze Jackson.

Quite possibly, you know him through Out of the Blocks, the podcast he co-produced with Aaron Henkin. Patrick wrote the ineffably cool, jazzy scores that accompanied the podcast, which produced intimate audio profiles of city blocks and their people.

When Henkin approached Patrick about collaborating on Out of the Blocks, he was simply hoping to use some of Patrick’s pre-existing music. He had been a fan of the musician since he interviewed him for a WYPR show called “The Signal.” But Patrick had another idea: What if he wrote customized soundtracks for each episode, incorporating the natural soundscape—the sizzle of the deep fryer, the whir of a dry-clean machine—into the music? Henkin was blown away.

“It was like asking to borrow someone’s used pickup truck, and then them saying, actually, let me build you a brand new Maserati from scratch,” he says with a chuckle.

Patrick became a co-producer of the show. He also got in the habit of taking striking black-and-white photos of the subjects featured on the pod. He and Henkin would hand deliver a print of the photograph to the interviewee, a way of saying thanks and staying connected.

Henkin says the photos also served as an icebreaker. “Like, everyone understands what a photo portrait is, but maybe not so much an audio portrait,” he explains. “It was almost like the pictures were easier for people to wrap their mind around than the audio.”

Henkin describes his partnership with Patrick as the most “productive, satisfying collaboration” of his life.

And now, Patrick is about to embark on one of his biggest challenges yet: heading up Peabody Institute’s new hip-hop program. Peabody will become the first conservatory in the world to offer a hip-hop degree.

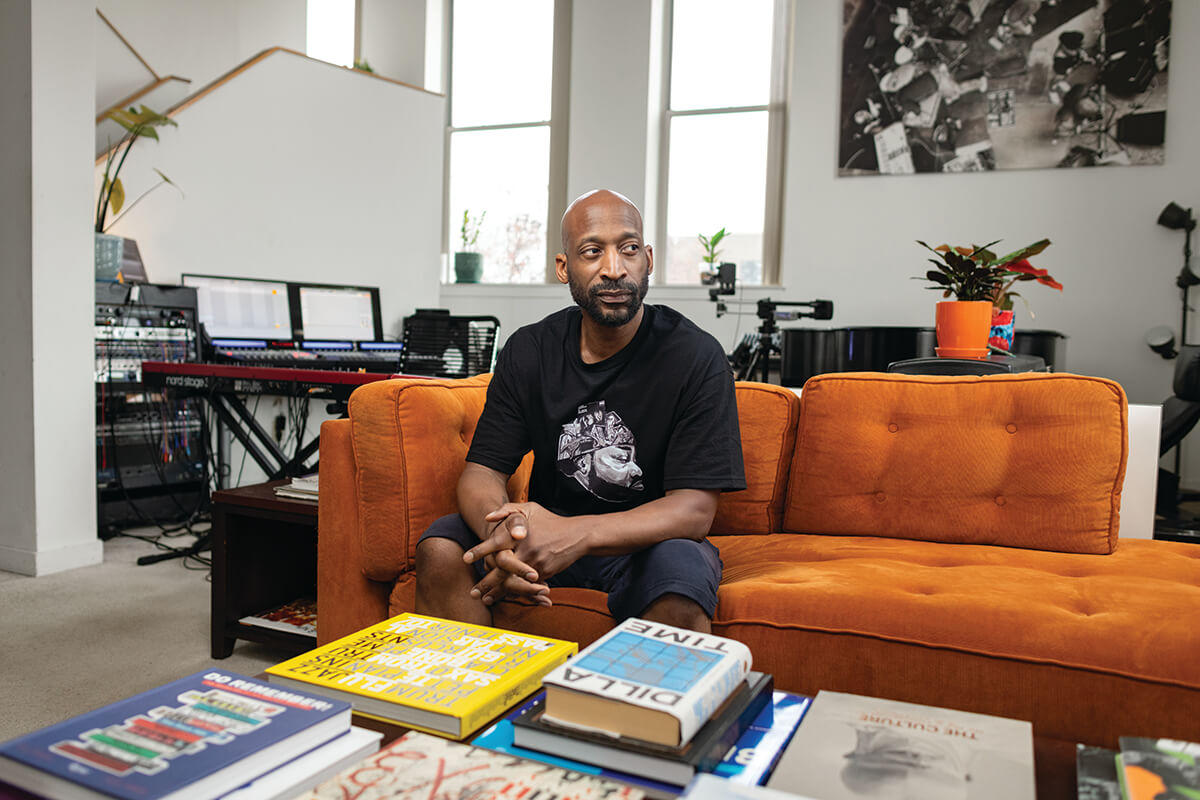

It’s an overcast day in November and Patrick is sitting in his two-floor apartment in the Bromo Arts District, reflecting on his career and life. Downstairs is a rather elaborate studio with all manner of microphones, video equipment, turntables, mixers, as well as that beautiful grand piano. His bedroom is upstairs. (He moved into this larger space in 2012.)

Patrick is dressed simply, in a dark gray thermal top, black jeans, and bare feet. He has an elegant way about him—a calm voice, a thoughtful stillness.

He says he’s excited about the prospect of building this hip-hop department from scratch—in what can only be described as a coup, Grammy Award-winning rapper and producer Lupe Fiasco will be joining the faculty—but he wants to make something very clear.

“I don’t think hip-hop needs any validation of any kind,” he says. “That’s not what this is about for me at all. I think Peabody and institutions of higher learning are going to learn a tremendous amount by having hip-hop. But entering into this space is not somehow a badge of honor.”

Fred Bronstein, Peabody’s dean, agrees. “Hip-hop was the logical next step for us,” he says.

He notes that Patrick had been an adjunct and then assistant professor at the conservatory since 2016—teaching hip-hop ensemble and Hip-Hop Music Production: History and Practice. And in general, the school has expanded its technology programs to prepare its students for an increasingly digitized world.

Today’s Peabody students are learning about film and video game scoring, computer music, sound design, musical engineering, and more, along with studying the established classical masters. They’ve had a jazz major since 2001. Bronstein feels that Patrick was uniquely positioned to teach at the school.

“One of the great things about Wendel is that he was trained as a classical pianist at a high level,” he says. “And he found his way into these other disciplines, most obviously hip-hop. I think he brings a breadth of knowledge and an understanding of how hip-hop fits into a wider musical context and relates to other disciplines.”

Bronstein also wants to dispel the stereotype of a Peabody student who is monomaniacally focused on classical music. They are young people who love music. And like most music-loving young people, they love hip-hop. “Kendrick Lamar won a Pulitzer Prize,” he points out.

So if Peabody is ready for hip-hop, the question remains, is hip-hop ready for Peabody? Eze Jackson, the local rap artist and impresario who has collaborated with Patrick on a variety of projects, welcomes this development.

“I think it’s exciting for hip-hop,” he says. “It’s exciting for Baltimore.”

He says he wishes that, back when he was a young man, a degree like this had been an option for him. “When I got out of high school, I was an emcee, but there was no place to study hip-hop. So I went in the Navy, pretty much to try to find myself,” he says. “I studied hip-hop on my own, as a student of the culture and the craft. But if I could have stayed home and gone to Peabody instead of going to the Navy, hell yeah!”

And Jackson thinks that anyone who sees this as somehow a sell-out of hip-hop culture is being painfully shortsighted.

“Hip-hop is such a limitless art form that I don’t think it gets credit for, so I think it’s dope that Peabody is taking this jump to be the first conservatory to offer it. It shows respect for a craft that we’ve always respected.”

What’s more, Jackson says Patrick is the perfect man to bring the subject to academia. “His knowledge of hip-hop is unmatched,” he says.

“IF I COULD’VE GONE TO PEABODY INSTEAD OF THE NAVY, HELL YEAH!” JACKSON SAYS.

Patrick is already receiving applications and he’s excited about the caliber of students who are applying to the major, which will officially launch in September. He envisions the program starting out small—maybe six to eight students in the first cohort—and growing from there.

“Peabody is an institution that is filled with very skilled students,” he says. “And that’s exactly what I want for this program. I want top level turntablists, MCs, beat boxers, and producers to come. And I’m excited to see what this first group of students is—it’s gonna be exciting for all of them, as well as for the new faculty.”

Meanwhile, there’s been another positive development in Patrick’s musical life. About 15 years ago, after accepting the fact that he may never play piano again, he started attending these “Out of Your Head” jazz improv sessions at the Windup Space. (Those sessions would ultimately become the inspiration for the Boom Bap Society.) He would play the electronic keyboard. And much to his surprise, he found that he could play. His index finger was still hard to control, but less so.

“That was pretty mind-altering for me,” he says. Apparently, the intuitive motion of improvisation—as opposed to the highly formal movement of classical performance—rewired his brain a bit. “And that’s when I started to approach [my focal dystonia] as more of a curiosity and a problem to be solved,” he says. “As opposed to, ‘I hope this thing just goes away.’”

Since then, it’s gotten better. Not perfect. But he’s making progress.

It’s not a coincidence that it was improv that brought on this revelation. It was the world of improv, of hip-hop, of electronica that saved him in a way, when he lost his ability to play Mozart and Chopin. He was able to thoroughly immerse himself in that music, reinvent himself—it brought him friends, fans, collaborators, incredible musical experiences across the world, all culminating in this new program at Peabody.

And now, in a perfect merging of Kevin Gift and Wendel Patrick, it had brought him back to the piano, his first love.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.