Art is always self-expression, but the reverse is not always true. This applies as much to the once rebellious graffiti on Nicosia streets as anything else

On the wall of a house near the Faneromeni underground car park in old Nicosia there’s a very polite printed note, in Greek and English: “Dear friend,” says the English version, “That you write [sic] slogans, opinions, graffiti. Please respect these private spaces.

“You should know that we respect your art, opinion and messages. We would gladly have a coffee with you, and discuss them. Thanks for understanding.”

The note is polite, but the impulse behind it is clear. The walls leading down to the car park were long ago designated by the municipality as a graffiti zone, a place for the capital’s budding street artists to show off their skills. The winding footpath teems with graphics and murals – but the artists’ zeal often spills over to include nearby shops and houses, especially as available space starts to run out. Hence, the note.

The note also makes another point, namely that graffiti – even when it’s messy and intrusive, maybe even ugly – nonetheless has value. Graffiti is artistic, it’s political. It can be discussed over coffee. Does all graffiti fit this description, though? What exactly counts as graffiti? Where does the form begin, and where does it end?

Savvas Koureas (AnexitiloN) puts the matter succinctly. AnexitiloN is his creative pseudonym, attached to a wide array of projects – most are on his website, anexitilon-art.com – from graffiti and mural art to airbrushing and bodypainting. He also teaches high-school DT and, until last year, also taught an afternoon course specifically on graffiti.

“Art is always self-expression,” he observes. “But self-expression is not always art.”

The same point ends up getting made, indirectly, at Faneromeni car park. On my first research jaunt to the area, I snap a photo of a slogan (in Greek) scrawled on the street-facing wall next to the car park: ‘Fuck Christodoulides’.

Alas, my photo is all that remains of that pungent message. When I visit again a week later, the graffiti has been hastily painted over – so hastily, in fact, that the letters are still faintly visible beneath the coat of paint. Even in a ‘free zone’, it seems, some self-expression is acceptable and some is not.

Then again, should graffiti be ‘acceptable’? Walk around Nicosia (or any city) and you’re much more likely to see the angry, unacceptable kind of graffiti – the kind the authorities would dearly like to paint over – than the artistic, aesthetically pleasing kind.

This is as it should be – because graffiti, in its purest form, is an act of rebellion, not to say desperation. Writing on walls is adjacent to vandalism, an act of creative destruction borne of helplessness and a young person’s need to express themselves – a way of publicly proclaiming a message, or idea, or creative talent for which no other outlet seems to exist in the system.

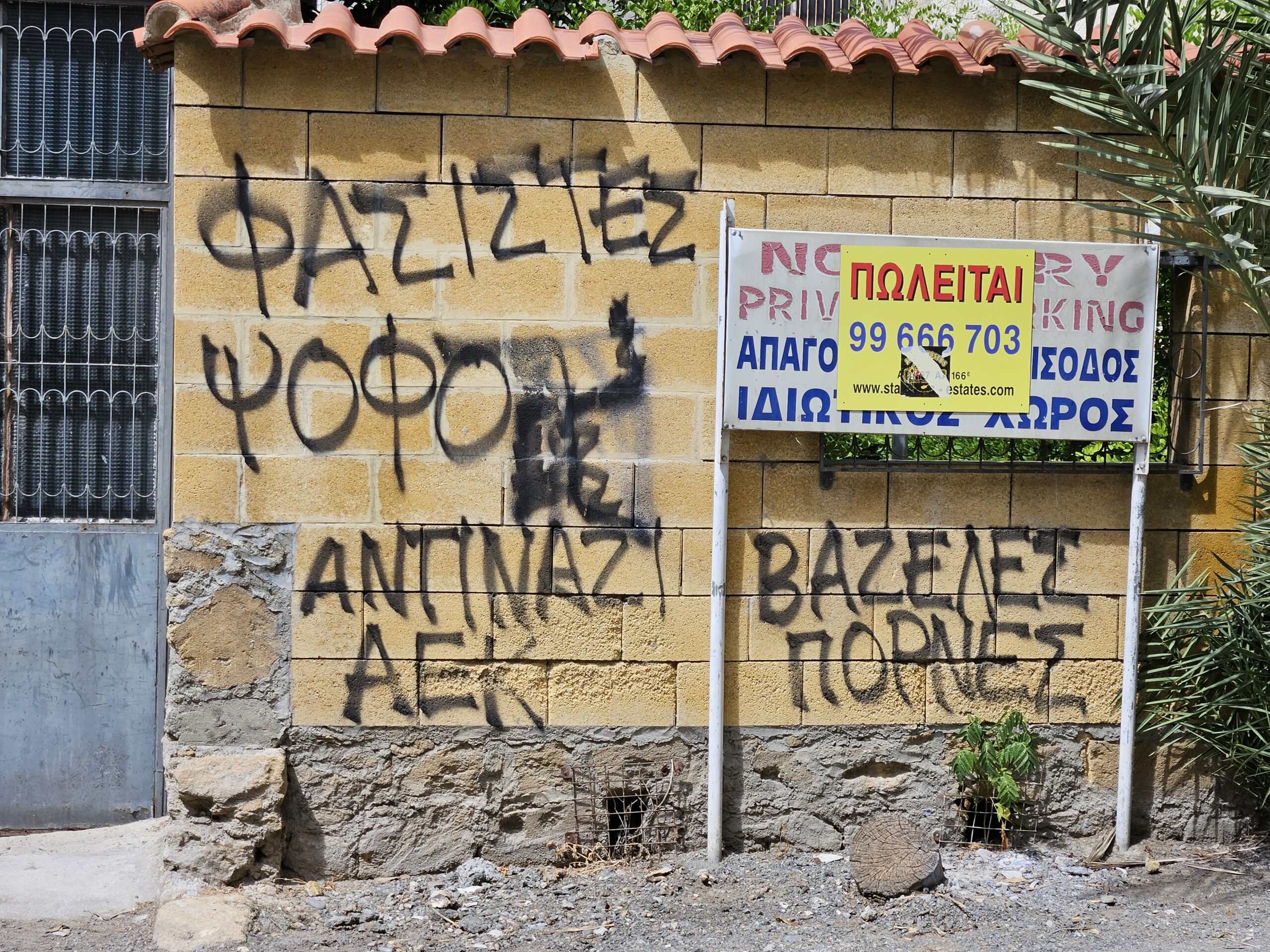

Sometimes, it’s true, the message is just immature – the obvious example being the ubiquitous football slogans. ‘Hohi Psofo’ says one, translating as ‘Hohi, die’, ‘hohi’ being the name Apoel fans use for Omonia fans. This is anti-social in a narrow, depressing way – not because it defaces property or offends social norms, but because it seeks to drag the viewer into a trivial spat that’s meaningless to anyone outside the two clubs. There’s something disrespectful in that.

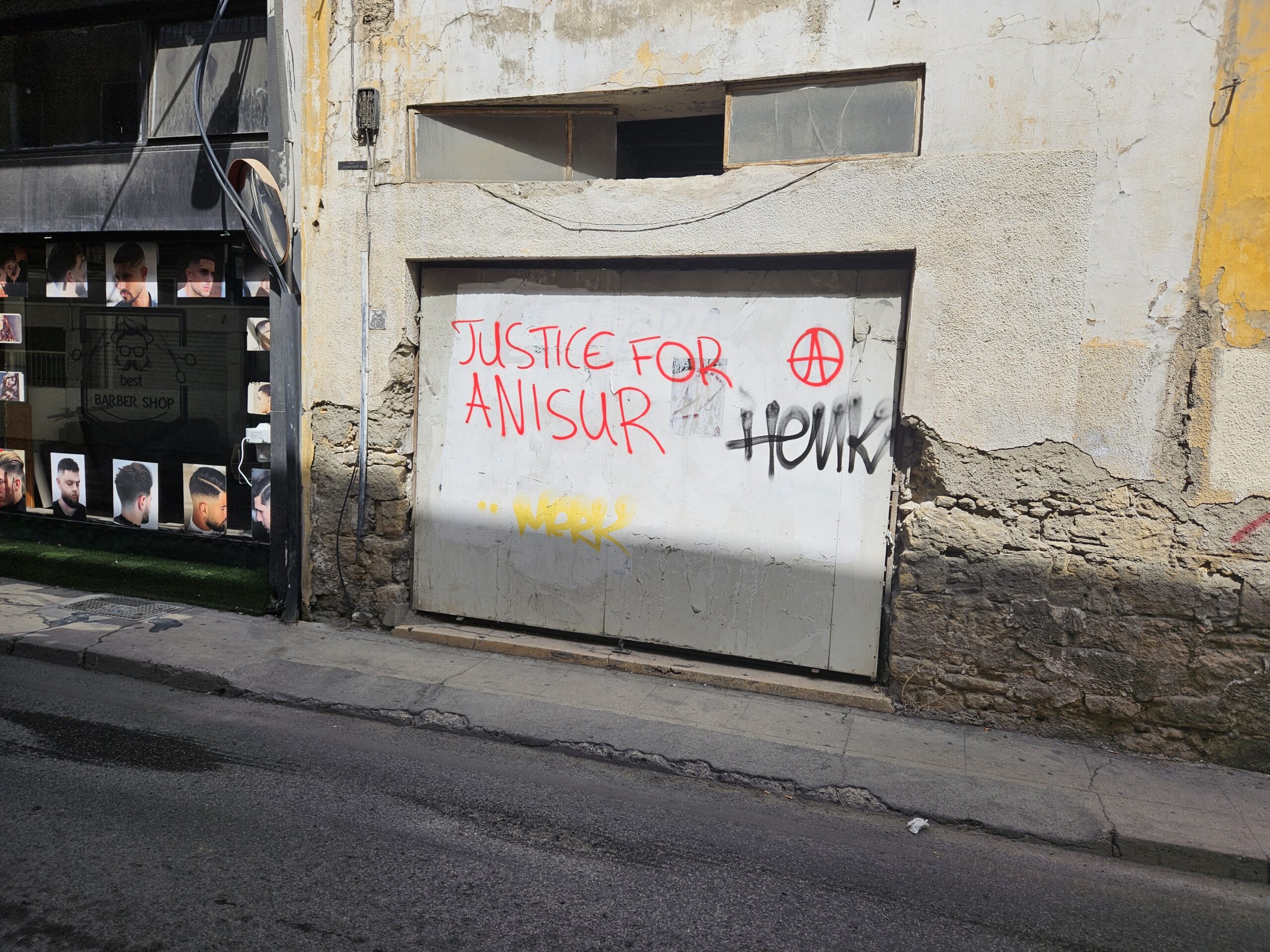

Other times, the message is dated – but still somehow poignant. ‘Justice For Anisur’ pleads an English-language scrawl in the old town, ‘Anisur’ being Anisur Rahman, the Bangladeshi migrant who died in April while trying to escape a police raid. Most passers-by may not even remember the case, six months later – but the message on the wall keeps it going, like a kind of living history.

It’s no accident that many of the graffiti hubs are situated in old Nicosia – a more dishevelled, more neglected part of town, home to migrants and bohemians. This, after all, is outsider art, operating on the fringes – more subversive than directly confrontational, scribbled in the dark when the authorities aren’t looking.

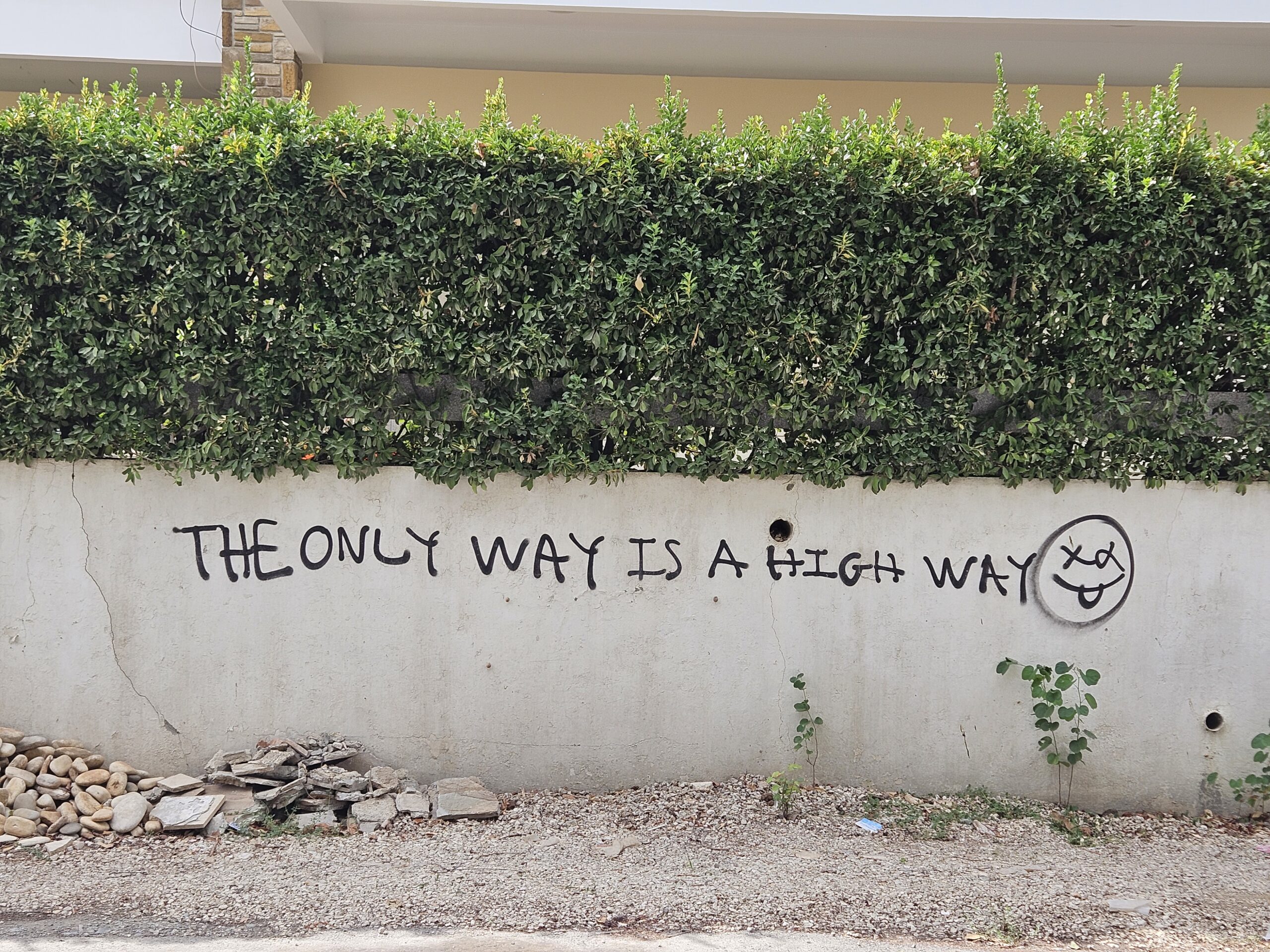

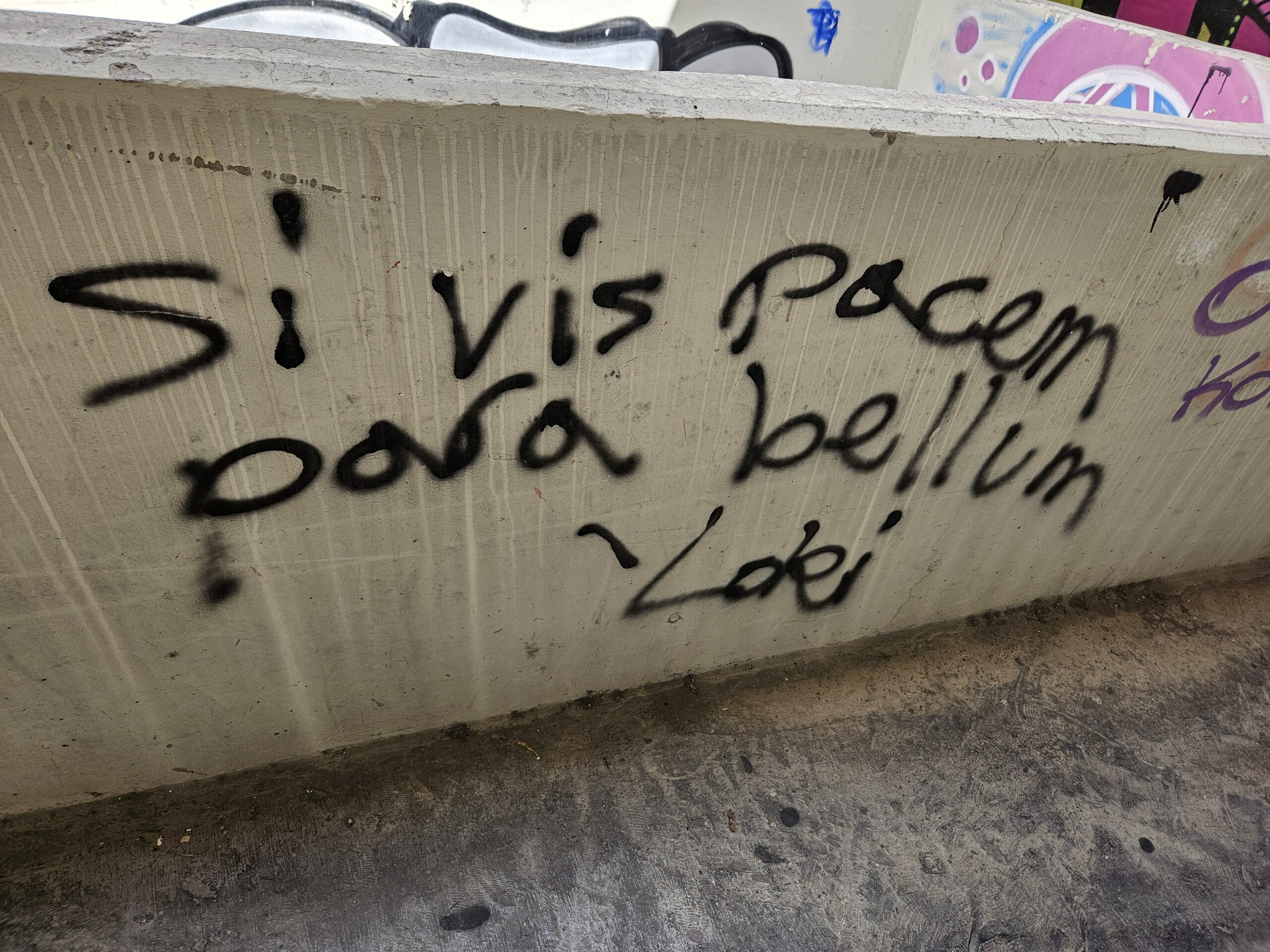

Graffiti isn’t unknown in posher neighbourhoods – but it tends to be less angry, more cerebral (football slogans excepted). ‘The only way is a high way’ puns a stoner’s scrawl on a wall near the American embassy, coupled with a suitably blissed-out smiley. ‘Adjust the Adjustment Beurau’ [sic] says one in the residential area of Dasoupolis – a message from a budding intellectual, even with the typo.

Walking around the old town, on the other hand, one gets assailed by more direct messages. ‘Kypros Gi Elliniki’ (‘Cyprus [is a] Greek Land’) says one – then, just a few yards further down, comes the opposite sentiment: ‘Skata Sto Ethnos’, i.e. ‘Shit on the [Greek] Nation’.

Anarchy signs are the most common symbol, while the slogans lean Left more than Right. ‘Refugees Welcome’ claims an eye-catching declaration, sprayed with luminous silver letters on a red wall. ‘We Are the Ones. Spread the Word’ says another, mysteriously. Then come the monikers of the creators themselves: ‘Wild Pest Pari’, ‘Tano Spek’ – not just printed but embellished, like a logo or visual signature.

This is where it gets more respectable – the grey area where graffiti evolves into painting, which is what you’ll (mostly) find on the walls of Faneromeni car park: giant lettering and great blobs of colour, the kind of in-your-face pop art that’s quote-unquote ‘edgy’ but can also be officially sanctioned as a burst of youthful creativity, making the city more interesting.

Then again, for Koureas, there is no grey area. This, he insists – i.e. murals and street art – is where graffiti as a form begins, the rest being just sloganeering and writing on walls. I show him ‘Adjustment Bureau’ as an example, but he shakes his head.

“No, that’s not art.”

But it’s graffiti, right?

“No. Graffiti is art.”

Doesn’t it convey an idea, though?

“Doesn’t matter. Otherwise you could say that a student’s exercise book is art – or that it’s graffiti.” He shakes his head again: “Just writing something down isn’t graffiti”.

That’s a whole can of worms, of course. Duchamp’s urinal and Andy Warhol’s soup cans famously implied that art ‘can be anything’ – but then can graffiti, too, be anything? What makes it special?

Some would say it’s the ‘street’ aspect, i.e. that graffiti is public art. But it’s also been exhibited in galleries, which are private venues. AnexitiloN himself works with private clients. Besides, it seems reductive to say that just anything can be graffiti, as long as it appears on a wall; ‘Hohi, die’ barely even rises to the level of self-expression, let alone art.

What about the rebellious aspect, then? The voice of the voiceless outsider, and so forth? But the sad truth is that graffiti has been co-opted, and no longer has much to do with rebellion or counterculture.

Note, for instance, that when I call AnexitiloN to arrange the interview he’s busy working on a mural to be installed in the headquarters of a corporate client, a forex company in Limassol.

At one point he mentions being invited by the government – this was in 2012, when Cyprus held the EU presidency – to paint graffiti on removable panels at the entrance to Larnaca airport, presumably to make us look cool and impress European guests. I myself recall visiting street artist Paparazzi in Larnaca some years ago, and seeing the entire street around his studio adorned with giant murals – undoubtedly with the municipality’s permission, and/or funding.

That’s the case with Faneromeni car park too: a designated ‘safe area’ that gives every indication of having been used for political purposes.

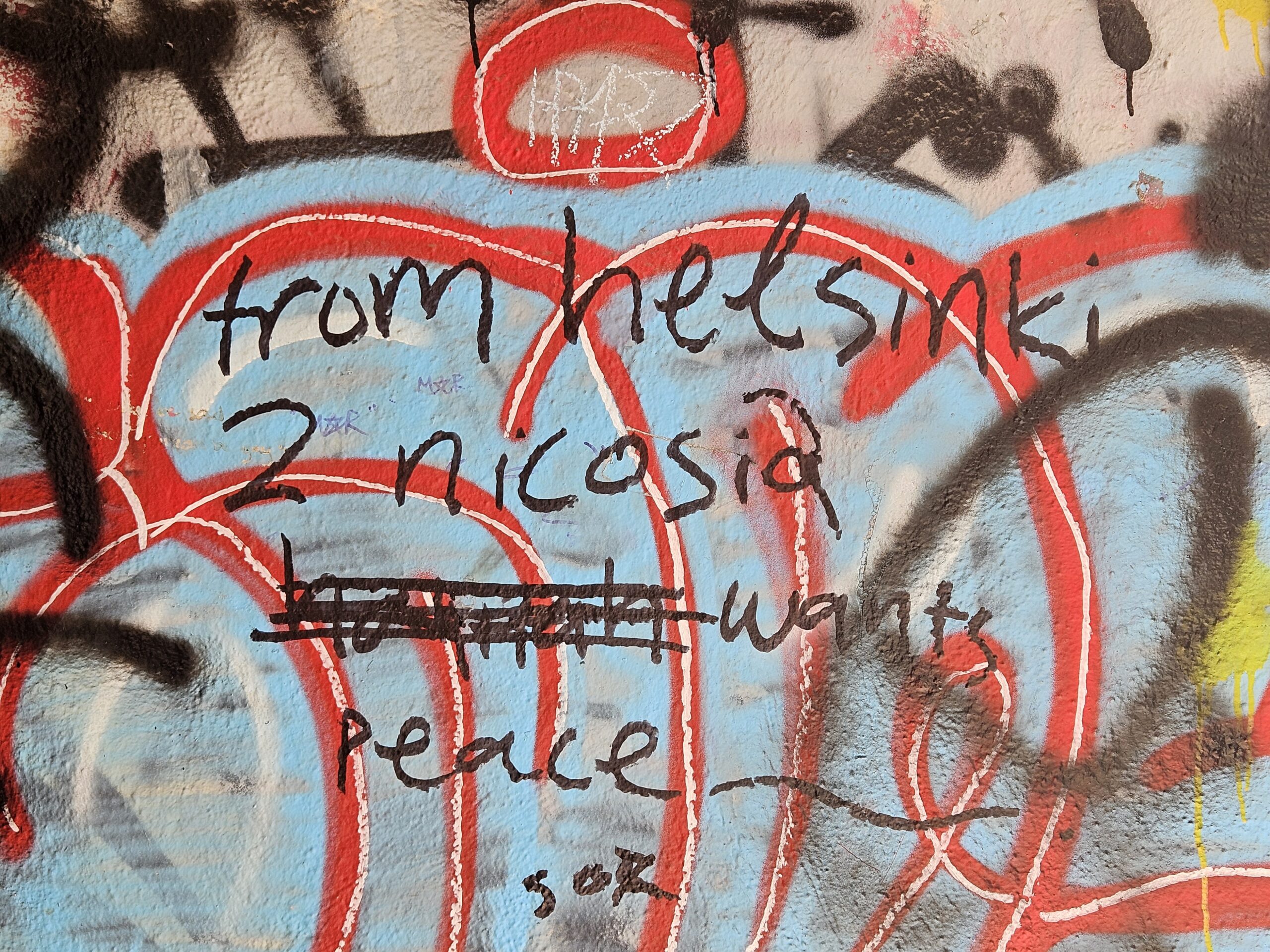

One artwork shows a silhouetted couple sitting in the branches of a stark, leafless tree, intertwined with a map of Cyprus and the Greek and Turkish words for ‘peace’. Elsewhere, a message reads ‘From Helsinki 2 Nicosia, [name crossed out] wants peace’. Easy to imagine the authorities sponsoring graffiti – as long as it’s bicommunal – and bringing foreign visitors to admire the creative outbursts of Cypriot youth.

AnexitiloN has a slightly different take. “It was out of necessity,” he says. “Society’s doing so badly these days that everyone’s holding [their anger] in, and they have to let it out somehow. If you don’t let them let it out with spray paint, they’ll let it out with rocks, then tomorrow with Molotovs, then the day after with bullets”. Graffiti, in short, is a safety valve, harking back to its rebellious aspect but ultimately managed from above – a controlled explosion, aimed at preventing bigger, uncontrolled ones.

In the end, the story of graffiti is a story of the counterculture in general, like the many other things – hip-hop, skating, street fashions – that began as ways of defying the mainstream, only to be swallowed up by it.

Yet it’s also more complex – because angry outsiders still write on walls to demand justice for migrants or trade football insults, even if that’s just self-expression and not really art (or even graffiti, for some pundits). Walk around Nicosia and you’ll witness the diverse, stirring evidence of people who saw a blank wall and literally couldn’t help themselves – because they had something to say (or draw, or paint), and needed to say it so badly they couldn’t wait for official channels to supply them with a safe area.

The streets around the car park are out of control too, even as ‘Fuck Christodoulides’ insults get painted over. Just down the road is an abandoned shop, its metal shutters permanently down – and they’re plastered with an absolutely massive signature (it must’ve taken ages), thick silver letters on a red background spelling out ‘RISHE TANO’.

Creativity spills over, heedless of boundaries. Meanwhile, round the corner, the neighbour’s printed note pleads politely.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.